A five-judge constitution bench on Monday unanimously upheld the constitutional validity of the Centre’s decision to abrogate Article 370 provisions that accorded a special status to Jammu and Kashmir.

The Supreme Court bench ruled that “J&K has no internal sovereignty” and had “full(y) and finally surrendered” to the Union of India through the Instrument of Accession of 1947, and that Article 370 was a temporary measure.

It, however, said the restoration of Jammu and Kashmir’s statehood “shall take place at the earliest and as soon as possible” and directed the Election Commission to hold elections to the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly by September 30, 2024.

In this context, the bench noted the submission of solicitor-general Tushar Mehta that the Union Territory status accorded to Jammu and

Kashmir following the August 2019 abrogation of Article 370 was only a “temporary” measure.

It said it would not interfere with Parliament’s legislative competence to carve out a separate Union Territory of Ladakh.

Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud, who headed the bench, wrote the main judgment on behalf of himself, Justice B.R. Gavai and Justice Surya Kant, while Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Justice Sanjiv Khanna wrote separate but concurring judgments.

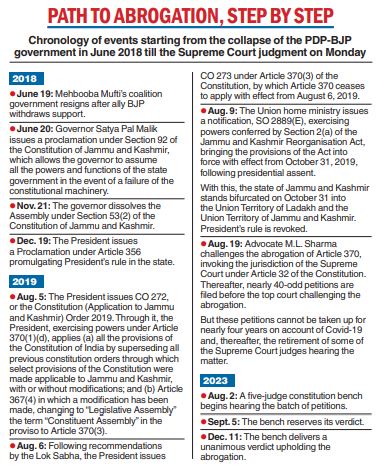

The bench dismissed a batch of petitions filed by individuals and organisations challenging the Centre’s decision to amend Article 370 via constitutional orders (COs) 272 and 273, issued by the President on August 5 and 6, 2019, in the light of a Parliament decision.

Sovereignty

The main judgment said the proclamation issued by Maharaja Karan Singh in the light of the Instrument of Accession reflected “full and final surrender of sovereignty by Jammu and Kashmir” to the Indian Dominion.

“Article 370 is an instance of asymmetric federalism. The people of Jammu and Kashmir, therefore, do not exercise sovereignty in a manner which is distinct from the way in which the people of other states exercise their sovereignty,” Justice Chandrachud wrote.

“In conclusion, the state of Jammu and Kashmir does not have ‘internal sovereignty’ which is distinguishable from that enjoyed by other states.”

The judgment said the separate constitution for Jammu and Kashmir as well as

Article 370 had been incorporated into the Constitution of India as temporary measures, and were therefore subordinate to the Constitution of India.

President’s powers

Some of the petitioners had argued that abrogating Article 370 required the consent of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir, which was dissolved decades ago. Therefore, they contended, the abrogation was invalid.

But the bench said the President’s power under Article 370(3) to abrogate Article 370 did not cease to exist upon the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir.

When the Constituent Assembly was dissolved, only the transitional power recognised in the proviso to Article 370(3) that empowered the Constituent Assembly to make its recommendations ceased to exist; it did not affect the power held by the President under Article 370(3), the bench ruled.

Some petitioners had also contested the presidential order’s application of all the provisions of the Constitution of India to Jammu and Kashmir.

To this, the bench said: “The President did not have to secure the concurrence of the government of the state or Union government acting on behalf of the state government under the second proviso to Article 370(1)(d) while applying all the provisions of the Constitution to Jammu and Kashmir because such an exercise of power has the same effect as an exercise of power under Article 370(3) for which the concurrence or collaboration with the state government was not required.

“The exercise of power by the President under Article 370(1)(d) to issue CO 272 is not mala fide. Thus, CO 272 is valid to the extent that it applies all the provisions of the Constitution of India to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Such an exercise of power is not mala fide merely because all the provisions were applied together without following a piecemeal approach….”

Not mala fide

However, the apex court declared as “constitutionally invalid” Parliament’s recourse to Article 367 to amend Article 370.

It said that Article 370 cannot be amended by the exercise of power under Article 367, which is only an interpretative clause and not an amending power or provision.

The bench, nevertheless, upheld the abrogation of Article 370 provisions since Parliament had, in addition to Article 367, also correctly invoked Article 370(3) in the matter.

The bench treated the recourse to Article 367 as an error, saying it involved no “mala fide” exercise of power.

“Recourse must have been taken to the procedure contemplated by Article 370(3) if Article 370 is to cease to operate or is to be amended or modified in its application to the state of Jammu and Kashmir,” the bench said.

“Paragraph 2 of CO 272 by which Article 370 was amended through Article 367 is ultra vires Article 370(1)(d) because it modifies Article 370, in effect, without following the procedure prescribed to modify Article 370. An interpretation clause (367) cannot be used to bypass the procedure laid down for amendment.”

However, the bench added: “The exercise of power by the President under Article 370(1)(d) to issue CO 272 is not mala fide. The President in exercise of power under Article 370(3) can unilaterally issue a notification that Article 370 ceases to exist.”

Statehood, Ladakh

Some petitioners had contested the Union government’s move to bifurcate the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state into two Union Territories.

The bench noted: “The solicitor-general stated that the statehood of Jammu and Kashmir will be restored (except for the carving out of the Union Territory of Ladakh).

“In view of the statement, we do not find it necessary to determine whether the reorganisation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir is permissible under Article 3.”

It added: “However, we uphold the validity of the decision to carve out the Union Territory of Ladakh in view of Article 3(a) read with Explanation I which permits forming a Union Territory by separation of a territory from any state….

“We direct that steps shall be taken by the Election Commission of India to conduct elections to the legislative assembly of Jammu and Kashmir constituted under Section 14 of the Reorganisation Act by 30 September 2024. Restoration of statehood shall take place at the earliest and as soon as possible.”

Some petitioners had argued that the constitutional changes of August 2019 were invalid because Jammu and Kashmir had no Assembly or elected government at the time and was under President’s rule.

But the bench said there was no limitation on Parliament’s power under Article 356, which relates to President’s rule, in taking decisions that “have irreparable consequences”.

Justice Kaul, the second senior-most judge of the Supreme Court who was on the bench, said in his separate judgment: “The Instruments of Accession signed by the various erstwhile princely states were to be reflected in the Constitution of India itself.

“However, insofar as Jammu and Kashmir state was concerned, Article 370 was a special procedure contemplated due to the ‘special conditions’ in the state and hope was expressed that in times to come, ‘Jammu & Kashmir will become ripe for the same sort of integration as had taken place in the other states’.”