The Supreme Court on Monday upheld by a 3:2 majority verdict the constitutionality of the 10 per cent reservation for the economically weaker sections that excludes the poor among the Dalit, tribal and OBC communities, saying it is neither discriminatory nor violative of any basic feature of the Constitution.

The court also suggested a review of the reservation system saying reservations need to have a “time span” and cannot go on forever. “Reservation should not continue for an indefinite period of time so as to become a vested interest,” the court said.

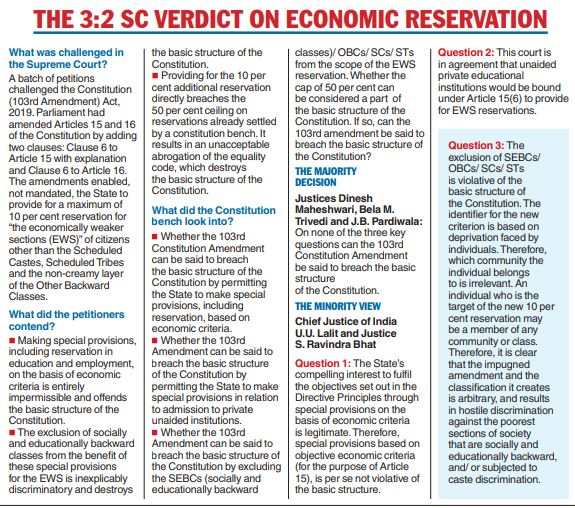

Justices Dinesh Maheshwari, Bela M. Trivedi and J.B. Pardiwala upheld the 103rd Constitution Amendment that provides for the EWS quota, each writing a separate judgment.

Outgoing Chief Justice U.U. Lalit, on his last day in office, and Justice S. Ravindra Bhat ruled against the quota in a minority verdict authored by Justice Bhat.

The majority view held that the 103rd Amendment had not breached the basic structure of the Constitution either by providing for reservation based solely on economic criteria, or by excluding the poor from among the SC, ST and OBC categories, or by breaching the 50 per cent ceiling for total reservation volume.

The dissenting view in the top court did not find fault with the economic criterion or the ceiling breach, either. It struck down the 103rd Amendment on the ground that it excluded the poor among the SCs, STs and OBCs from its ambit, saying this amounted to practising “constitutionally prohibited forms of discrimination”.

Justice Maheshwari, in his 155-page verdict, said: “It is beyond doubt that using the doctrine of basic structure as a sword against the amendment in question and thereby to stultify State’s effort to do economic justice as ordained by the Preamble and DPSP (Directive Principles of State Policy) and, inter alia, enshrined in Articles 38, 39 and 46, cannot be countenanced.

“This is essentially for the reason that the provisions contained in Articles 15 and 16 (forbidding any kind of discrimination, and mandating equal opportunity in public employment, respectively)… providing for reservation by way of affirmative action, being of exception to the general rule of equality, cannot be treated as a basic feature. A valid classification does not require mathematical niceties and perfect equality; nor does it require identity of treatment.

“If there is similarity or uniformity within a group, the law will not be condemned as discriminatory, even though due to some fortuitous circumstances arising out of a particular situation, some included in the class get an advantage over others left out, so long as they are not singled out for special treatment,” Justice Maheshwari said.

“The expression ‘economically weaker sections of citizens’ is not a matter of mere semantics but is an expression of hard realities.”

Justice Bhat, in his dissenting verdict, said the EWS quota was “per se not violative” on the ground of being based solely on an economic criterion, but it had to go because it excluded the poor among the SCs, STs and OBCs from its ambit.

“I feel… that this court has for the first time, in the seven decades of the republic, sanctioned an avowedly exclusionary and discriminatory principle. Our Constitution does not speak the language of exclusion,” he said.

“In my considered opinion, the amendment, by the language of exclusion, undermines the fabric of social justice, and thereby, the basic structure. This amendment is deluding us to believe that those getting social and backward class benefits are somehow better placed (than the poor among the forward castes).”

The sole woman judge on the bench, Justice Trivedi, in her 24-page concurring views with Justice Maheshwari, observed: “However, at the end of seventy-five years of our independence, we need to revisit the system of reservation in the larger interest of the society as a whole, as a step forward towards transformative constitutionalism.”

She and Justice Pardiwala, who wrote a concurring 117-page verdict upholding the EWS quota, said there was a need to have a time span for reservations as they cannot continue for all time.

The majority view noted that the representation of the Anglo-Indian community in Parliament and the Assemblies had ceased by virtue of the 104th Amendment. “Therefore, similar time limit if prescribed, for the special provisions in respect of the reservations and representations provided in Article 15 and Article 16 of the Constitution, it could be a way forward leading to an egalitarian, casteless and classless society,” Justice Trivedi said.

Justice Pardiwala said the 103rd Amendment signified Parliament’s intention to expand affirmative action to hitherto untouched groups who suffer from similar disadvantages as the OBCs in competing for opportunities.

“If economic advance can be accepted to negate certain social disadvantages for the OBCs (creamy layer concept), the converse would be equally relevant. At least for considering the competing disadvantages of Economically Weaker Sections,” he said.

“I am of the view that the words ‘weaker sections’… cannot be read to mean only the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes….”

The majority view said the argument that the State may adopt any poverty alleviation measures but cannot provide reservation for EWS by way of affirmative action proceeds on the assumption that reservation was itself reserved only for the SCs, STs and OBCs.

“Such an assumption is neither valid nor compatible with our constitutional scheme. This line of argument is wanting on the fundamental constitutional objectives, with the promise of securing ‘justice, social, economic and political’ for ‘all’ the citizens; and to promote fraternity among them ‘all’. Thus viewed, the challenge to the amendment in question fails on the principle of distributive justice,” it said.