Economist Kaushik Basu has described the current economic slowdown in India as collateral damage from “the erosion of trust caused by the country’s drift toward illiberalism”.

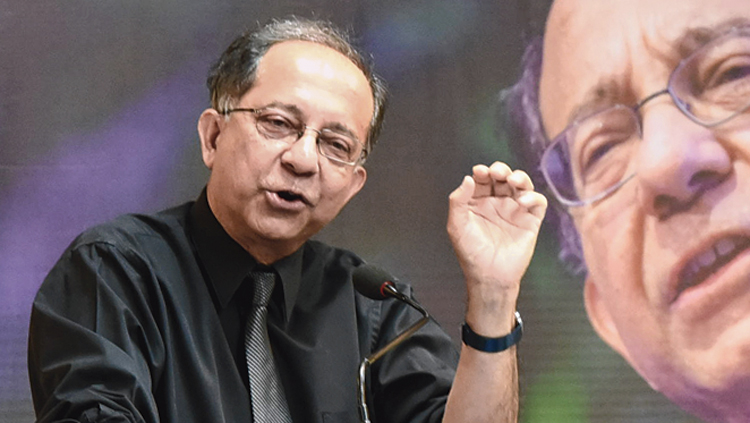

“The current slowdown is mostly collateral damage, the result of an erosion of trust caused by the country’s drift toward illiberalism. India can boost its economy again by reclaiming and building on its progressive heritage,” Basu, the chief economic adviser to the Indian government from 2009 to 2012, wrote in a opinion article in The New York Times newspaper on Wednesday.

In the article titled “India and the Mistrust Economy”, Basu, a professor of international studies and economics at Cornell and chief economist of the World Bank from 2012 to 2016, seeks to explain the seemingly contradictory signals associated with the country’s economy.

He also warns that “countries with strong governments often end up with weak economies, and India, after years of impressive growth, risks becoming one of them”.

India was among the 10 countries that made the most progress in a recent World Bank report on the ease of doing business in 190 countries. “Yet major indicators show that its economy is slowing down sharply,” Basu writes and cites data that says inequality is rising as well.

The economist concedes that “inequality was worsening before the present administration took office” but adds that “with growth slowing down and unemployment rising, the effects are more painful”.

Basu asks in the Times article: “So how can it be getting easier to do business in India, apparently, even as by some measures, economic growth is decelerating? These simultaneous developments, far from being conflicting, actually explain each other.”

He explains that the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business rankings “are primarily an assessment of how good a country’s laws look on paper rather than how they operate in practice.

By the report’s own account, ‘approximately two-thirds of the data embedded in the Doing Business indicators are based on a reading of the law’. In other words, a government can adjust its regulations in a way that ensures it will make progress along the index, even if the changes have minimal effect on the ground.”

Basu points out that “real growth, on the other hand, depends on how well the laws are actually carried out”.

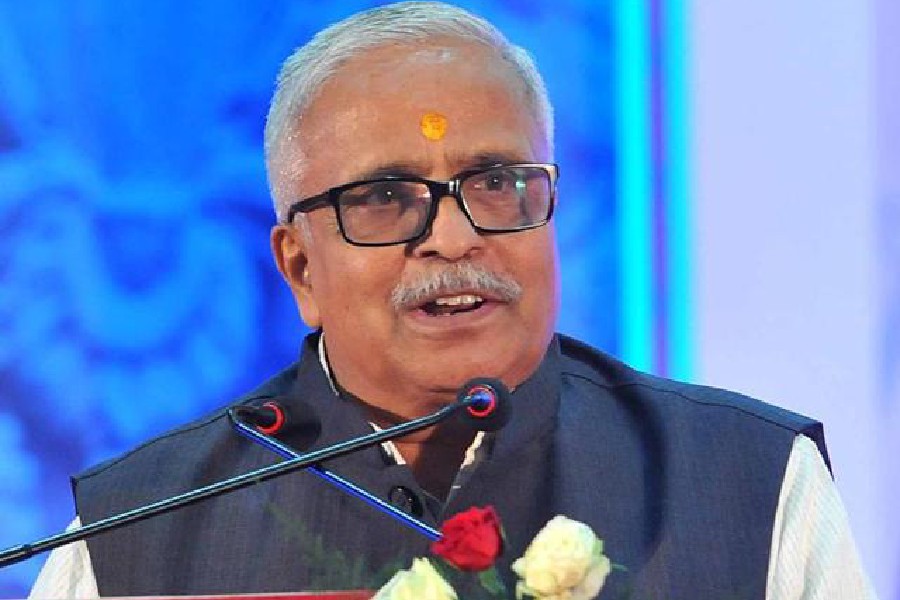

The economist then addresses a subject that the Narendra Modi government has so far been accused of viewing with disdain.

“These days in India, divisiveness is increasing throughout society while trust in the government is declining, at least among major economic actors. Consider this indirect indicator of waning confidence, which is often overlooked: what economists call ‘investment’, the part of national output that leaves out consumables like food, clothing and housing and refers to production that will enhance future productivity, such as the building of machines, factories and infrastructure,” Basu writes.

The economist then underscores the importance of investments. “Both a body of economic theory — including the seminal work of Robert Solow at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) — and much real-life evidence, especially from the superfast growth of East Asian economies in the 1980s, suggest that in emerging economies with plentiful labour, a rise in the investment rate boosts overall growth.”

Tracing the investment trajectory of the country, Basu adds: “India was a low-investment country for many years after independence in 1947. Investment did not exceed 20 per cent of gross domestic product until the late 1970s. It crossed the 30 per cent mark for the first time in 2004-05 and climbed to 39 per cent in 2011-12. India had begun to look like, and grow like, an East Asian economy in the 1980s. But then investment started to decline, and by 2016-17 it was back to around 30 per cent.”

Why has investments dipped in the country? Basu offers a reason: “A drop in investment is usually connected to a lack of trust in the present and the near future. When businesses worry about a country’s policy environment, they hesitate to sink money into it. A government’s heavy-handed interference in the market — such as the Modi administration’s decision to ban some paper currency in late 2016 (demonetisation) — or general fractiousness, in politics or within a bureaucracy, can hurt confidence in the economy.”

Basu does not shy away from wading into a territory that some economists find tricky. “Economists don’t much like to admit this, but a country’s economic performance depends as much on its politics as on its economic policies.”

Then he underscores in the Times article how priority was accorded in building political institutions in India in the immediate years after Independence.

“Starting at independence, India invested in political institutions first — establishing democracy, free speech, independent media, secularism and protections for minority rights. After World War II, as nations broke free from the yoke of imperialism, there were other progressive leaders who tried this — in Indonesia and Ghana, for example — but those efforts did not last. Coups, chaos or conflict caused democracy to collapse in one nation after another, bringing in military rule or religious strife. India was an exception, with its liberal Constitution, regular elections and powerful Supreme Court.”

Basu points out that “India’s growth in the early decades after independence was sluggish”. He also admits “one can debate whether India’s early investment in progressive politics was the right choice” but makes clear his position by saying “I think it was”.

Basu makes his case for preserving that legacy. “But having made that investment, it would be a colossal mistake now to squander the political capital that choice generated — especially after the economy finally did take off, first in early 1990s and spectacularly so after 2003.”