Two human skulls discovered in a southern Greece cave decades ago and now dated to be 210,000 years and 170,000 years old represent the earliest evidence for modern humans outside Africa, scientists said on Wednesday.

A new scientific analysis of the two skulls, found during archaeological excavations in the Apidima cave in Greece’s Mani peninsula in the late 1970s, suggests that modern humans dispersed out of Africa much earlier than previously believed.

The study supports suggestions that Homo sapiens, or modern humans, had ventured out of Africa multiple times but, for various reasons, died out, failing to establish long-lasting populations until an out-of-Africa migration around 60,000 years ago.

The study’s findings were to be published in the journal Nature on Thursday.

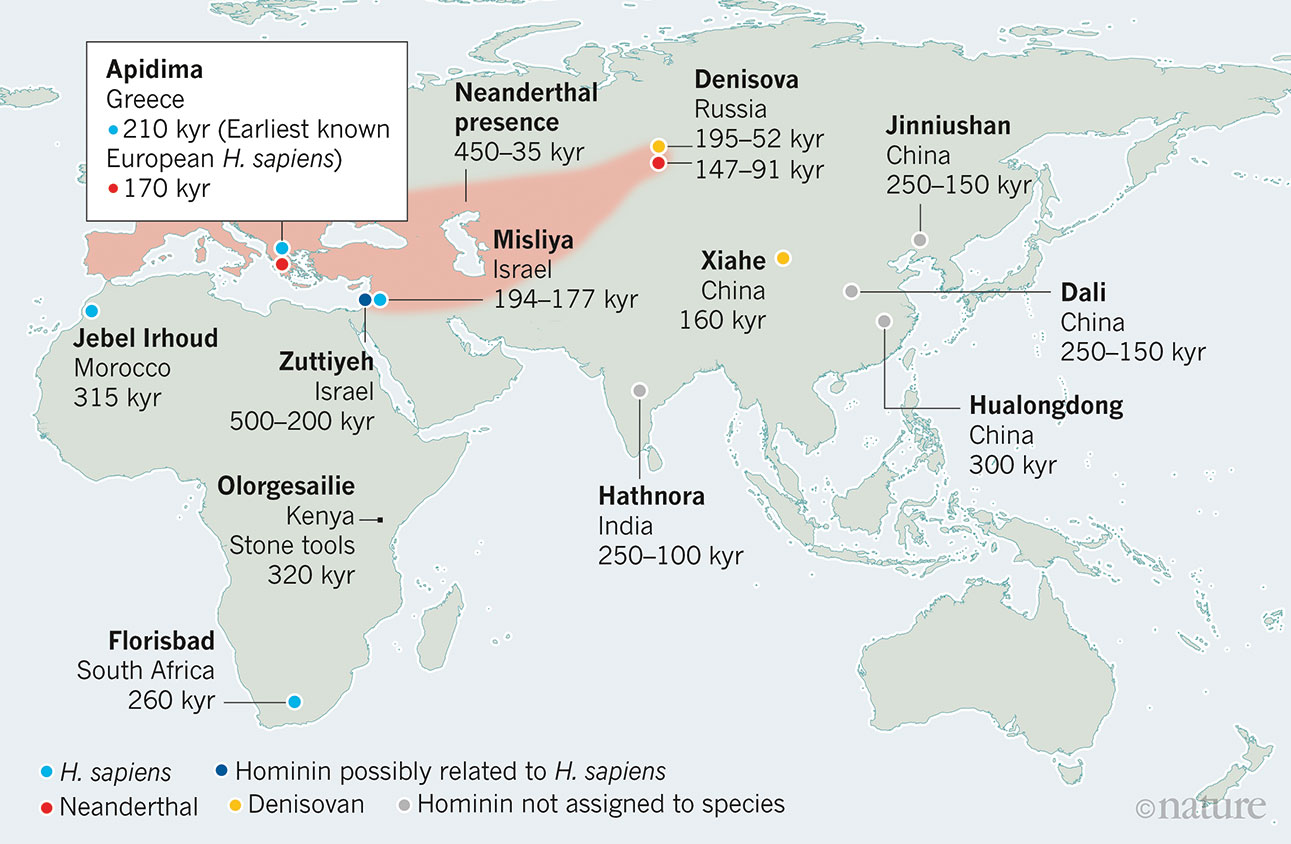

Almost all human-origin specialists agree that modern humans evolved somewhere in Africa. The idea is backed by the earliest known Homo sapiens fossils — found in Morocco and dated to 315,000 years ago, and in South Africa and dated to about 260,000 years ago.

But there is uncertainty over the dates for the earliest out-of-Africa dispersals. Until now, the earliest fossil evidence for modern humans outside Africa was from the Misliya cave in Israel, where scientists had found a jawbone dated between 194,000 and 177,000 years old.

Map shows locations of key early fossils of Homo sapiens, or modern humans, and related species in Africa and Eurasia. Photo credit: Nature

Genetic evidence strongly suggests that all the humans alive today can trace their ancestry to groups of modern humans that trudged out of Africa into Eurasia along different directions between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago.

“We’re seeing evidence of multiple human dispersals — not limited to one major exodus out of Africa, but multiple dispersals,” said Katerina Harvati, a palaeo-anthropologist at the University of Tubingen, Germany, and lead author of the study.

“But the earlier ones did not leave any genetic contribution to modern humans living today.”

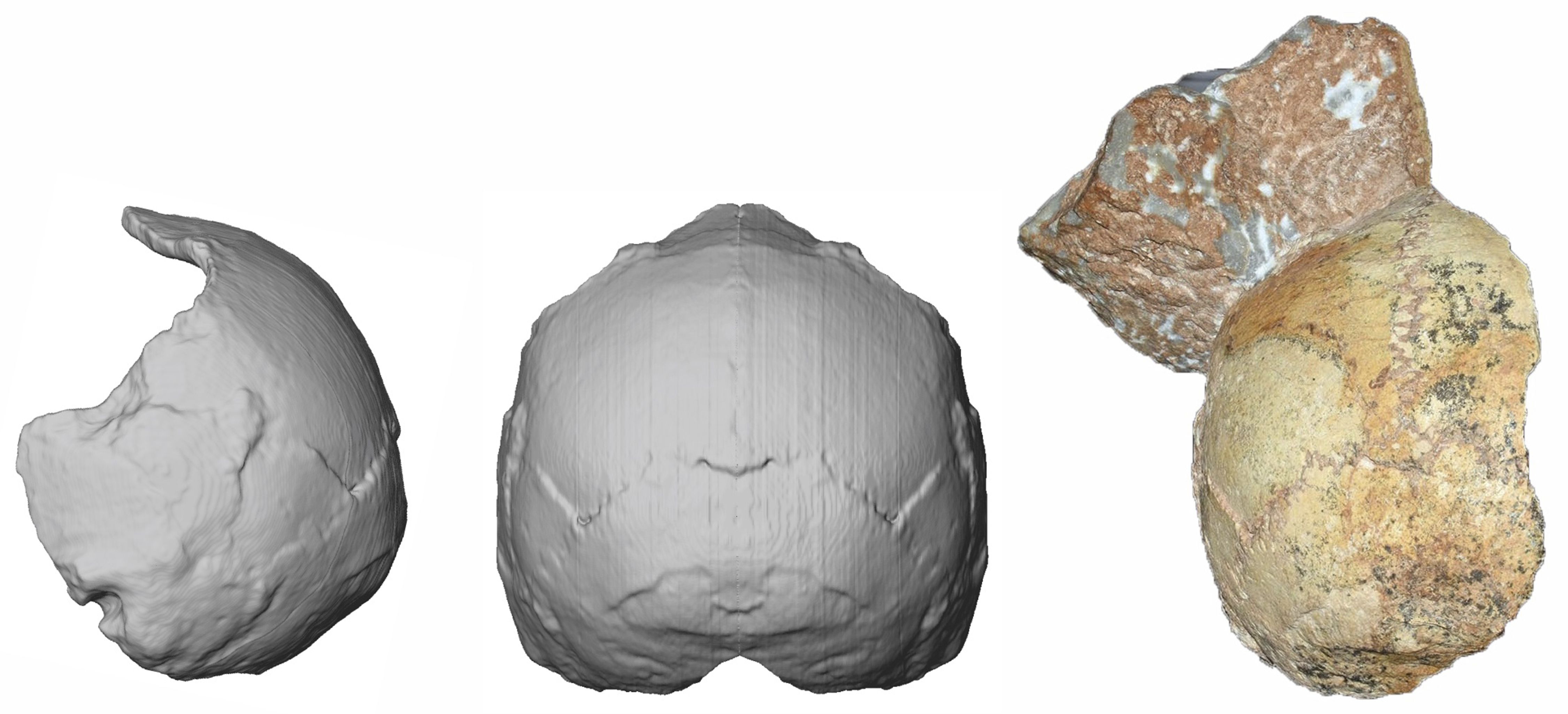

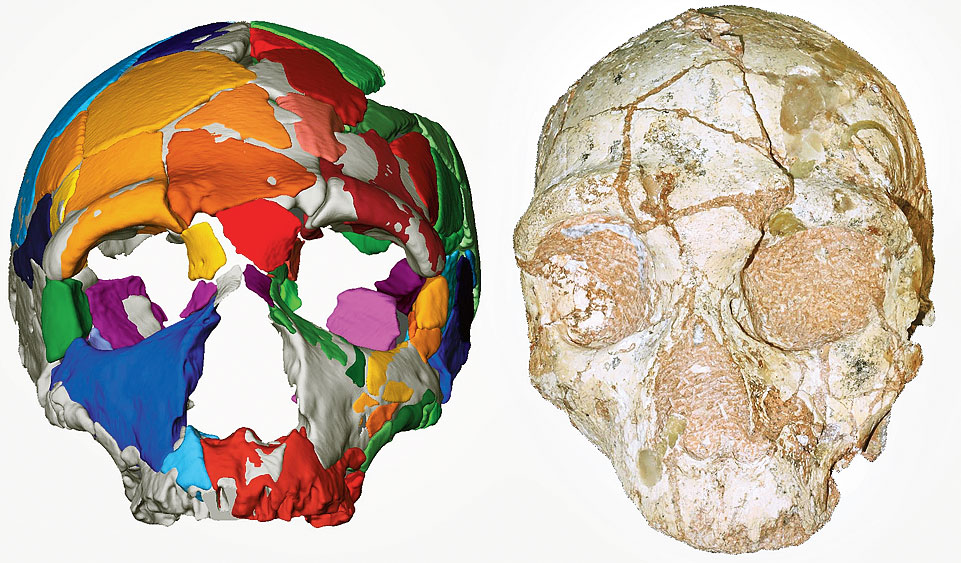

The older of the two Apidima skulls has a mix of modern human and ancestral features such as a rounded back of the skull, a characteristic unique to modern humans, and predates the previously reported oldest Homo sapiens in Europe by 150,000 years.

The younger skull shows features associated with the Neanderthals, an archaic human species that once roamed Eurasia, coexisting and possibly interbreeding with modern humans until the Neanderthals went extinct between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago.

How a Homo sapiens skull from 210,000 years ago and a Neanderthal skull from 170,000 years ago came to rest close to each other at the Apidima site remains unknown.

Scientists also do not know yet why the populations resulting from the early out-of-Africa dispersals, such as those to Israel or Greece, did not survive.

Cranium, over 170,000 years old (right), and its reconstruction (left) Credit: Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of Tubingen, Germany

“We don’t know for sure,” Harati said. “They persisted for a long time in Israel. They seemed to have been around for several thousands of years. I would suspect (that) small populations made it all the way to Greece — smaller than the source populations in Israel or in Africa.”

The researchers speculate that there could have been contact, or perhaps even conflict, between the Neanderthals and the Apidima people. Why both groups disappeared remains a mystery.

Eric Delson, professor of anthropology at the City University of New York, has in a scientific commentary on the Apidima study in the same issue of Nature called for the use of genetic or palaeo-proteomics tools to assign dates to other contemporaneous fossils. These fossils, dated to between 300,000 and 150,000 years old, were found in various parts of Asia.

A skull discovered by geologist Arun Sonakia in 1982 along the banks of the Narmada is the oldest modern human fossil found in India. It is estimated to be between 100,000 and 250,000 years old.