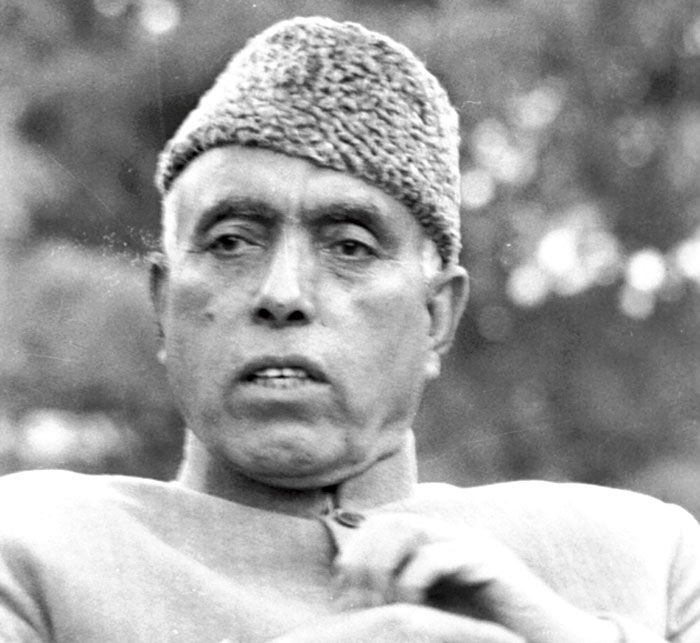

The mausoleum of National Conference founder Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, who got Article 370 incorporated in the Indian Constitution, usually attracts a few visitors and more abuses.

These days, there are no visitors and only abuses.

Abdullah has for generations been the subject of scorn for Kashmir’s pro-azadi camp. With the provision of Article 370 that gave the state its special status now scrapped, the number of his admirers is bound to shrink further.

In drawing-room discussions and at shop-corner gatherings, many Kashmiris are cursing him for the fate that has befallen them.

The mausoleum of the Grand Old Man of Kashmir politics, once described by his admirers as the “tallest politician of the state” and the “Lion of Kashmir”, is a living testimony to his rise and fall.

“In normal times, we get some visitors. Only occasionally, like on Sheikh Sahab’s birth or death anniversary, hundreds would come. There has been no visitor in the past 10 days (after the scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status),” a policeman guarding the grave, on the western bank of the Dal Lake near the Hazratbal shrine, told The Telegraph.

“More than visitors, you get to see people on motorcycles or in cars hurling abuses. They say things like ‘Baba aaya jahannum (father be

in hell). This happened always, but is happening more often now,” the policeman added.

That is a far cry from 1983, when Abdullah commanded a lot of respect among a section of the population, with lakhs of people joining his last journey.

The Kashmir Valley is under curfew but a stretch of the road adjoining the grave is among the areas where restrictions have been eased, giving people the opportunity to pass that way.

In an irony of fate, Abdullah has no admirers on the other side of the azadi-India divide too. His son Farooq Abdullah is under house arrest and grandson Omar Abdullah is in jail. Both Farooq and Omar have been chief ministers.

Mohammad Sultan, a diehard National Conference activist all his life, has sworn not to visit Sheikh Abdullah’s grave ever again.

“I have never abused him before but that man is responsible for our fate. He promised us a better life by choosing to accede with a secular and democratic India but history has proved him wrong,” the resident of the old city of Srinagar said.

Kashmir became a part of the country in October 1947 after the last Dogra monarch, Hari Singh, signed the instrument of accession with the Union of India.

But for many Kashmiris, Sheikh Abdullah is the real architect who, as one of the most popular leaders, lent his support to the document.

Kashmir owed it to Abdullah for incorporating Article 370 in the Indian Constitution, one of the reasons he became a hero or bab (father) to many in his generation and the next.

The later generations — preceding militancy and after — curse him for turning Jammu and Kashmir into an Indian state.

The NC founder was the prime minister of the state from 1948 to 1953, when he was deposed and sent to jail for reportedly espousing the azadi cause that year. He gave up the struggle in 1975 and opted for power, being then demoted to chief minister, which is seen as the beginning of his fall.

His popularity started dwindling in the late 1980s. He was publicly abused for the first time after a film on Libyan freedom fighter Omar Mukhtar was screened at Srinagar’s Regal Cinema. Abdullah’s pictures were torn.

The rise of militancy in 1989 was the last nail in the coffin of his popularity, turning him into a villain for many.

Militants had made a couple of futile attempts to desecrate his grave in the early 1990s. A concertina-wire fence was strung around the mausoleum during the 2008 summer agitation because of fears that pro-azadi protesters might damage his grave and that of his wife, Akbar Jahan, buried next to him.

Five men from the 20th battalion of the Indian Reserve Police guard the mausoleum round the clock. A chowkidar and three gardeners are employed for its upkeep.

Mohammad Saleem, the chowkidar at the grave for the past two decades, seems to be still an admirer of Abdullah, revealing how his spiritual powers used to heal the sick.

“There are both types of people, some venerate him and some hate him. I have seen people entering the premises (of the mausoleum) bare-foot out of veneration and offer fatiha (seek blessings for him),” Saleem said.

One of the policemen guarding the grave, however, said they feared violence at the mausoleum if Kashmir erupted again.

The establishment has not withdrawn or downgraded the mausoleum’s security, as is the case with many pro-India politicians from his party and other outfits. Many others have been jailed.