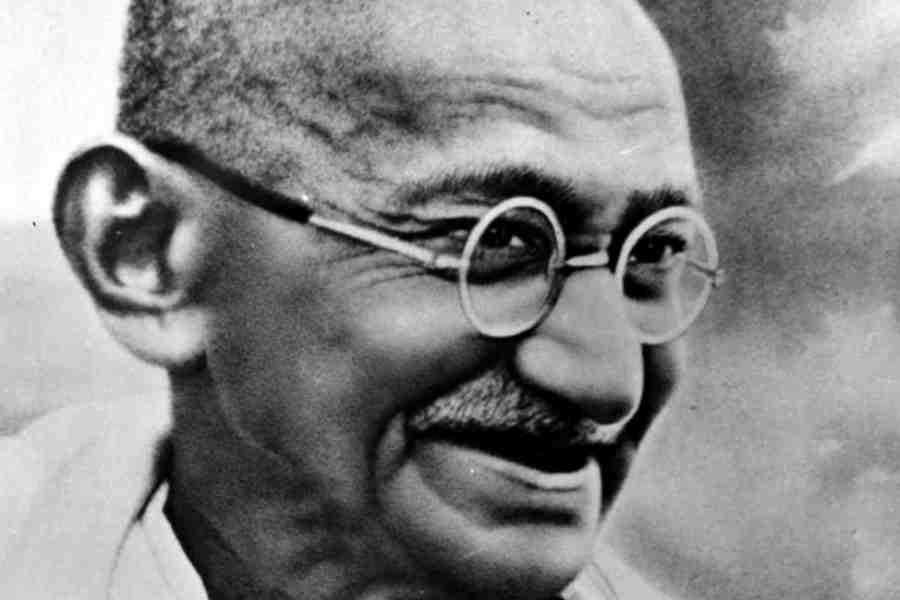

The sociopolitical world view of the BJP and the Sangh parivar is riddled with severe contradictions. Along with its lip service to secularism, it constantly indulges in the impossible effort to revere disparate figures like Gandhi as well as Savarkar and Godse in the same breath. Prabhat Patnaik, emeritus professor of social sciences at JNU, dissects these irreconcilable anomalies in this dialogue with Subhoranjan Dasgupta, professor of human sciences.

Q: When Narendra Modi is abroad, in Japan or the US, he pays homage to Gandhi standing in front of his bust. At the same time in Bihar, his senior minister, Giriraj Singh — to give just one flagrant example — hails Godse as a ‘patriot’ and ‘worthy son of India’. Modi does not protest. How would you explain this drastic doublespeak?

Patnaik: Many people may not know that the RSS had openly celebrated Gandhiji’s assassination by distributing sweets, and that Nathuram Godse, according to his brother’s testimony, had never left the RSS, his action being in conformity with the RSS attitude. This attitude is also reflected in that of the BJP which is fundamentally opposed to the secular agenda of our freedom movement and to Gandhiji in particular who had worked strenuously to maintain communal harmony. (The RSS and the BJP deny these charges.)

The Giriraj Singh-Pragya Thakur position eulogising Godse, therefore, represents the true feelings of the RSS and of the core BJP, leaving out here the non-RSS outsiders who may have joined the BJP for opportunistic reasons and who may not share to the same extent the RSS antipathy towards Gandhiji. In the core BJP, therefore, there is no ‘double-think’ on the matter of eulogising Godse, though there is ‘doublespeak’ that is forced on it by Gandhiji’s popularity with the masses.

In paying obeisance to Gandhiji, the BJP and Narendra Modi opportunistically try to ingratiate themselves with the popular mood while concealing their own position which is fundamentally different. The height of this opportunism was reached when for a while it had re-christened its ideology ‘Gandhian Socialism’ despite being neither Gandhian nor socialist. Interestingly, when it abandoned this tag, there were no ideological struggles within it or angry resignations, indicating that nobody had taken it seriously anyway.

It is for the same opportunistic reason that the BJP tries to appropriate Netaji who is well-known for his secular commitment and abhorrence for communalism.

Q: Yet another example. After inaugurating the new Parliament, in the course of 15 minutes, Modi reveres Gandhi and then Savarkar, one a martyr and the other accused of assassinating him (Savarkar was later released for lack of evidence). No two personalities could be more different. Is it possible to straighten out this tortuous contradiction?

Patnaik: It is an example of the same ‘doublespeak’. It is Savarkar who is their real icon, but they are constrained to pay obeisance to Gandhiji. Incidentally, Savarkar’s portrait in Parliament was installed during Vajpayee’s Premiership, which shows the pervasiveness of the BJP’s adoration for him, and, by the same token, the ritualistic hollowness of their obeisance to Gandhiji. Savarkar may have been released for lack of evidence in the Gandhi assassination trial, but the fact that “a group around Savarkar” carried out the assassination is indubitable, as Sardar Patel the home minister had asserted at the time.

I believe that Savarkar does not deserve to be condemned because of his “mercy petitions” to the colonial government written from the Andaman cellular jail: there is nothing ignoble about being broken by inhuman jail conditions as long as one does not betray comrades. By the same token, however, he does not deserve to be adulated despite the mercy petitions: there is nothing noble about being broken by inhuman jail conditions either.

Indeed, there is ‘doublespeak’ even in the BJP’s adulation of him: the real cause for their adulation is his propagation of Hindutva, though the excuse they offer for it is his early anti-imperialism which he had renounced when he came to Hindutva.

Q: While addressing the American Congress on India’s secularism and pluralism, Modi borrows the visionary diction of his bête noire, Pandit Nehru. At home, his party and the Sangh parivar are hellbent on obliterating Nehru from public memory. How long will this borrowing and rejection continue?

Patnaik: Fascist outfits typically lack any theory. They have prejudices but no coherent set of theoretical beliefs. They also know that prejudices cannot be paraded openly in all settings; so they cannibalise on others’ theoretical constructs whenever the need arises to present something ‘respectable’ to the world. But since it is cannibalisation, the source from which they cannibalise would vary from one setting to the next. In the setting of the American Congress and on the theme of India’s secularism and pluralism, Jawaharlal Nehru is an ideal source and he gets quoted despite Modi’s intense prejudice against him.

But this points to something else, namely the complete lack of seriousness behind Modi’s public utterances. The sole objective of these utterances is grandstanding, making a grand impression at the moment by saying whatever would achieve this, and forgetting it the next moment when there is a new audience with new sensibilities.

This drama of borrowing from Nehru’s vision and rejecting that vision can go on ad infinitum. But here again, it must never be forgotten that the rejection of Nehru is real, while the borrowing from him is just sham, a pose adopted for effect at a particular moment to impress a particular audience.

Q: Narendra Modi himself conducted a virulent, polarising, election campaign supporting the Bajrang Dal in Karnataka. Cow vigilantes under the protection of the same Bajrang Dal have allegedly killed five Muslim cattle traders in the last few months. After all these, the Prime Minister labels his governance ‘steadfastly secular’ in foreign countries. Should we then agree with (CPM leader) Sitaram Yechury’s comment, ‘Modi worships Gandhi abroad and Godse at home’?

Patnaik: I would put it differently: ‘Modi secretly worships Godse both at home and abroad, but mouths admiration for Gandhi especially abroad and occasionally at home.’ But there is another aspect that needs to be noted. Apart from holding certain core beliefs which are nothing else but prejudices, and apart from specialising in striking grand poses, there is a curious inability on Modi’s part to impose any discipline and order on the army of Hindutva supporters.

This is in contrast with classical fascism. In Germany, for instance, there had been a purge against Rohm and the SA who constituted the rank and file of the Nazi party, to meet the demands of the German military staff: in other words there was no laissez-faire in hooliganism when it came to the followers of the fascist movement. In India, by contrast, there is an obvious lack of willingness to act against a Monu Manesar, a Kapil Misra or a Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh who brazenly flout the law of the land, not just because they are Hindutva supporters (that of course has to be a necessary condition for impunity), but because dirtying one’s hands in such quotidian mess, which would necessarily entail courting unpopularity among some sections of Hindutva supporters, goes against Modi’s cultivated grand image of being above it all.

This underlies Modi’s intriguing silences on certain burning issues, and also means, incidentally, that there is no proper day-to-day administration; instead there is the flourishing of an army of local Hindutva ‘warlords’.

Q: The Prime Minister is repeatedly invoking Gandhi’s historic call for India’s independence — ‘Quit India’ — to lambast the Opposition INDIA coalition. This dependence on Gandhi’s unforgettable slogan prompts us to recall the role of the Sangh parivar in the struggle for India’s freedom. How would you qualify this role, as ‘dubious’, ‘treacherous’ or ‘nefarious’?

Patnaik: I would call the RSS role ‘disruptive’. It remained subservient to the colonial administration, and when the entire country was swept into the anti-colonial struggle, its cadres remained scrupulously aloof from it. When the provincial Congress governments resigned in 1939 protesting India being dragged into the war without its people’s consent, the Hindu Mahasabha, the BJP’s ideological ancestor, continued to be in government in three provinces in partnership with the Muslim League: Bengal, Sind and the NWFP; and when the Quit Movement was launched, Hindutva’s icon Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a minister in Bengal, wrote a letter to the governor of Bengal denouncing it vehemently.

The Hindutva elements were so contemptuous of the anti-colonial struggle that even at the time of independence, RSS chief M.S. Golwalkar had predicted that the leadership of that struggle could not administer an independent India and that the British would have to be invited back. It is ironical in this context that the RSS has now taken on the mantle of ‘nationalism’ and calls all its critics ‘anti-national’: the Indian ‘nation’ came into being through the anti-colonial struggle in which the RSS was never a participant. Its founder K.M. Hegdewar had been a Congressman during the Khilafat years but gave up any association with the anti-colonial struggle after coming to Hindutva. Hindutva was in effect a negation of anti-colonial partisanship.

Its votaries would no doubt claim that they believe in Hindutva ‘nationalism’. But two points must be noted. First, this is antithetical to the inclusive anti-imperialist nationalism on which our modern nation-state is founded and would destroy the nation that has emerged through a prolonged and arduous struggle; second,

religion cannot provide a basis for ‘nationalism’ as the break-up of post-partition Pakistan has already demonstrated.