Indian scientists have coaxed genetically engineered bacteria to add, subtract, and even identify prime numbers between 0 and 9, in laboratory experiments that they say mark an advance towards a novel computational technology.

The researchers at the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics (SINP), Calcutta, have shown that clusters of bacterial cells in glass flasks can be harnessed to perform complex and abstract computational tasks hitherto performed only by human brains and modern computers.

“This is another step towards the long-standing goal of developing biocomputers — computational machines made from living cells," said Sangram Bagh, an associate professor at the SINP’s division of biophysics and structural genomics who led the research effort.

While modern computers have long outpaced humans in performing computational tasks, current microprocessor-based computers have limitations because of energy consumption, costs and size. Silicon computers cannot be shrunk to the size of living cells.

Multiple research teams across the world have earlier created logic gates — the fundamental electronic circuits in computers — using living cells and demonstrated computational operations such as adding and subtracting using such biological logic gates.

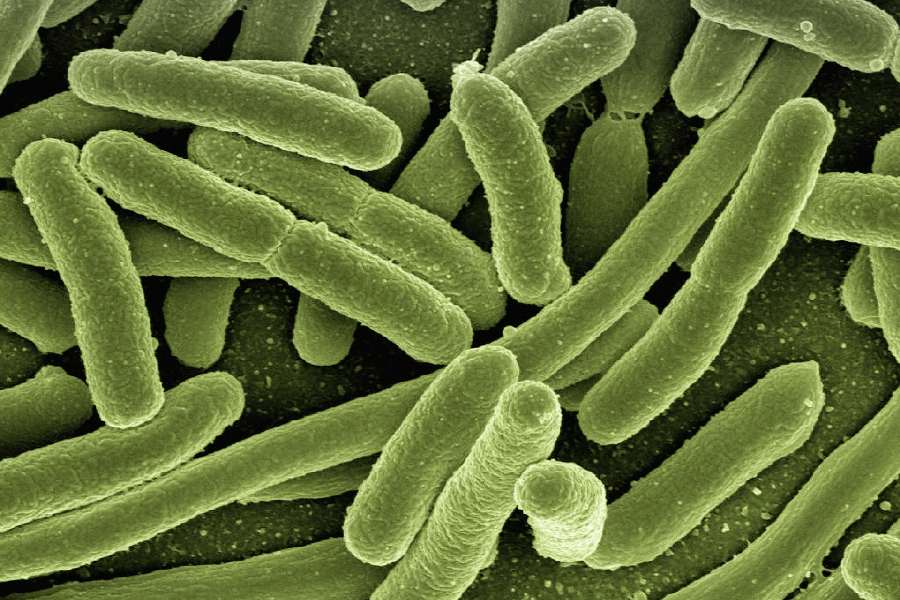

At the SINP, Bagh and his colleagues have used genetic engineering and concepts from artificial neural networks — computer systems inspired by the architecture of the human brain — to turn E coli bacterial cells into computational machines.

The scientists tweaked the E coli genomes, introducing 14 different genetic circuits, to create 14 types of the bacteria. Each type of bacteria serves as a building block that can be mixed and matched with others in a liquid broth to create computational devices for specific computational tasks.

They used the bacteria to add, subtract, and perform 10 complex and abstract computational tasks. Two of these 10 tasks included identifying prime numbers between 0 and 9 and vowels between the letters A and L, both tasks classified as yes or no problems.

“Using chemical language, we question the bacteria: Is 4 a prime number? Is 7 a prime number? The bacteria respond with a yes or a no, secreting a green protein when the answer is yes, and a red protein when the answer is no,” Bagh said.

Bagh and coauthors Deepro Banerjee, Saswata Chakraborty, Biyas Mukherjee, Ritwika Basu, and Abhishek Paul published their work in the journal Nature Chemical Biology this week.

“This is ground-breaking work,” said Syed Shams Yazdani, the head of the microbial engineering group at the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, New Delhi, who was not involved with the research.

“Each bacterial cell has been engineered to behave like a single neuron that interacts with others to make a decision. This has never been done before.”

Mohit Kumar Jolly, assistant professor, Centre for BioSystems Science and Engineering at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, who was also not connected with the SINP research said the work represents an advance in computational science and fundamental biology. “Mammalian cells make decisions all the time and we currently have very little understanding of this decision-making process,” Jolly said.

Bagh said that the study also raises questions about the nature of intelligence. “We imagine that identifying prime numbers or vowels is something only humans or computers can do, but now we have bacterial cells doing the same thing.”