Antara Nat, a 10-year-old Class III student from Chhattisgarh, spends her days doing acrobatic stunts to entertain young and old in coastal Odisha’s villages.

Her brother Ashis, 7, enrolled in Class I, too chips in with tightrope-walking acts. Their father Shameylal plays popular Hindi and Odia songs on a portable music player while their mother keeps a protective eye on the children lest they fall and suffer injuries.

In the middle of the show, Shameylal asks: “Why are you attempting this risky stunt?”

Antara replies: “For food. Please pay us Rs 10 or Rs 20 or give us some rice.”

Shameylal then asks the onlookers not to disappoint the child.

Under the Child and Adolescent Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, employment of children below 14 years in any occupation — even if it’s a family vocation — is illegal. Those aged below 18 are banned from hazardous occupations.

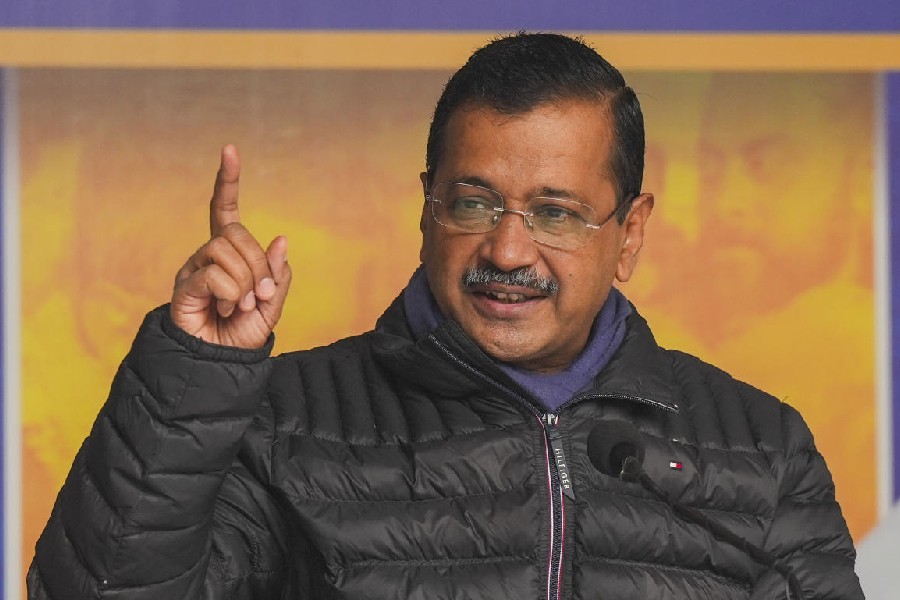

Ashis walks on tightrope at a village in Odisha. Telegraph picture

But Antara’s parents are happy. They say they earn about Rs 250 from a performance at a village. The family, from Chhattisgarh’s Janjgir district, spends the nights in a tent.

“My children are enrolled in a government school but we have no money. There’s no work available back home. We came to Odisha two months ago to earn a livelihood,” Shameylal said.

Antara and her brother know nothing about the government’s National Child Labour Project, which aims to rescue and rehabilitate working children.

Under this programme, surveys to identify working children are to be conducted at the district level and the rescued children enrolled in training centres to be provided bridge education and vocational training.

Nor has the education ministry’s offer of free education, school uniforms and a midday meal done anything for the two tribal children. The rural job programme, MGNREGA, has not prevented Shameylal from moving out with his family.

“This is our family occupation. We can stop this if we get sustained work and liveable wages,” Shameylal said.

Data provided by junior labour minister Rameswar Teli in the Lok Sabha on August 9 showed a rise in the number of rescued child labourers but did not provide an estimate of the number of working children.

In a written reply to a question from Congress member Vishnu Prasad MK, the minister gave a year-wise breakup of children rescued from workplaces since the financial year 2017-18.

Under the National Child Labour Project, 47,635 children were rescued and rehabilitated in 2017-18, the number rising to 50,284 in 2018-19, to 54,894 in 2019-20 and to 58,289 in 2020-21.

Mitra Ranjan, coordinator of the Right to Education Forum which raises issues of access to education, said that according to the 2011 census, India had 1.01 crore child labourers.

“There should be proper mapping of child labourers. Most of them are from Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, backward classes and poor families and are likely to remain outside school. Their future is at risk,” Ranjan said.

He said the RTE Act had not been implemented properly in the decade since its enactment. The shift to online education, necessitated by the pandemic, has further created a digital divide and made access to education more difficult for poor and rural children.

“Such students are almost certain to be found working. During the period the schools remain closed, the government should provide them with digital devices and Internet facilities,” Ranjan said.

“The best solution is for the schools to reopen at the earliest, with the observance of Covid protocols.”

A report titled “Child labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road ahead”, release by the International Labour Organisation and Unicef in June, estimated that 16 crore children — 6.3 crore girls and 9.7 crore boys — were working globally at the beginning of 2020, accounting for almost 1 in 10 of all children worldwide.

Nearly half of the child labourers — 7.9 crore — were in hazardous occupations.

An analysis suggests that a further 89 lakh children will be in child labour by the end of 2022, as a result of rising poverty driven by the pandemic, unless urgent measures are taken, the report said.

It recommended that governments help mitigate the poverty and economic uncertainty faced by these children’s families, and ensure free and quality schooling.