Thirty-two years ago, a former high court judge was brought out of retirement to be elevated to the Supreme Court in an initiative without parallel in independent India.

Justice Fathima Beevi’s extraordinary appointment has again become a topic of discussion in legal circles following the Supreme Court collegium’s recommendation on Wednesday to elevate nine judges to the apex court.

One factor behind that is the Narendra Modi government’s proclivity to sit on the collegium’s recommendations, often for months.

If the government does not decide on the latest recommendations by September 1 — a tight deadline by its standards — one of the candidates, Justice Hima Kohli, will have retired.

The second factor is an expectation — corroborated by an apex court judge to this newspaper —that the collegium might then explore the possibility of elevating Justice Kohli the way Justice Fathima Beevi had been in 1989 in the pre-collegium era.

Justice Kohli, now chief justice of Telangana High Court, will reach 62, the retirement age for high court judges, on September 1. However, she will get a tenure of three more years if appointed by then to the Supreme Court, where the retirement age is 65.

Asked whether they expected the Centre to decide on the latest recommendations in another 12 days, legal experts said they hoped Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana’s “no-nonsense” approach and ability to assert himself would persuade the government to do so.

But they also cited the government’s serial delays in clearing judicial appointments and tendency to object to certain candidates or seek clarifications about others.

They contended that if the government didn’t play ball and Justice Kohli had to retire on September 1, the collegium could well exercise the same option that had led to Justice Fathima Beevi becoming the country’s first woman apex court judge.

Justice Fathima Beevi had retired on April 29, 1989, as a Kerala High Court judge. She was elevated to the Supreme Court on October 6, 1989, at a time the government selected judges for appointment in consultation with the judiciary. She retired on April 29, 1992.

While the Constitution has no provision for a judge being recalled from retirement and elevated to a higher court, Justice Fathima Beevi’s appointment was not challenged.

One standout example of the Centre delaying judges’ appointments has been the six-month stalemate over Justice K.M. Joseph’s elevation to the Supreme Court after the collegium recommended him in January 2018.

Political and legal circles had accused the government of victimising Justice Joseph because he had as an Uttarakhand High Court judge in April 2016 quashed the Centre’s imposition of President’s rule on the hill state, thus restoring a Congress government.

Before the 2018 standoff, the Centre had also rejected a request Justice Joseph had made in May 2016 seeking a transfer to Andhra Pradesh High Court on health grounds.

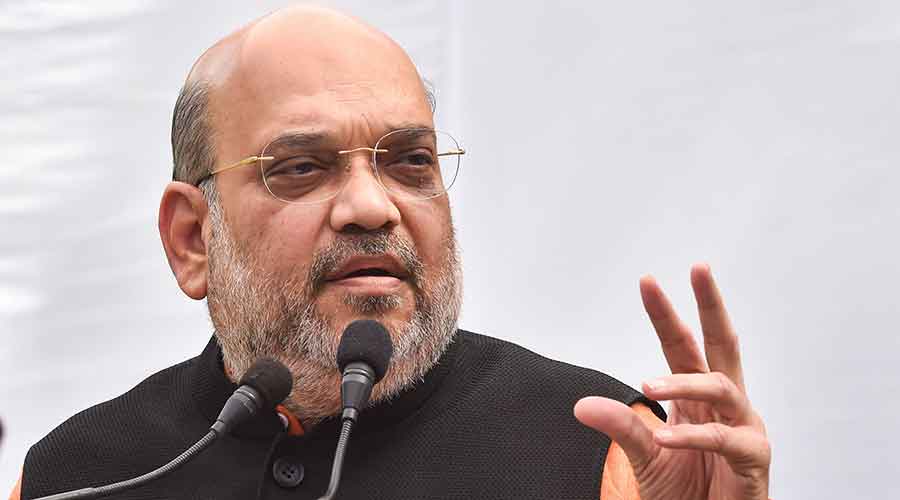

Another collegium recommendation that the Centre had blocked concerned Justice Akil Kureshi, who had in 2010 sent Amit Shah, now Union home minister, to CBI custody in the Sohrabuddin Sheikh “fake encounter” case.

The collegium had sought Justice Kureshi’s transfer as chief justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court but the government’s stalling forced it to recommend him for chief justice of the much smaller Tripura High Court. This the government accepted.

This apart, several Chief Justices of India such as Justice T.S. Thakur, Justice Ranjan Gogoi, Justice S.A. Bobde and Justice Ramana have often pulled up the Modi government, in the courtroom and outside, for sitting over judicial appointments, including those to the quasi-judicial tribunals.

As recently as last week, an angry Justice Ramana had told solicitor-general Tushar Mehta to close down the tribunals if the government could not fill the vacancies. Currently, the high courts and tribunals face more than 40 per cent vacancies.

However, government sources have often accused the collegium of tardiness in recommending candidates instead of abiding by the memorandum of procedure that says replacements should ideally be named six months before an incumbent judge’s retirement.

Government sources have suggested the collegium often recommends a candidate six months or even a year after a vacancy arises.