Over 2,300km separate Amethi and Ernakulam. Or do they?

The BJP is in power in Uttar Pradesh, where Amethi is located. The CPM heads the ruling coalition in Kerala, where Ernakulam falls.

The CPM is the sworn enemy of the BJP, and the Left party often describes itself as the sole and true opponent of Narendra Modi’s brand of politics.

But on one count, little separates the two parties — media management. Not just these two parties but almost all organisations that wield power in India have tried to browbeat the media.

The key difference now is that such bullies have a playbook at hand. A template that has achieved critical mass — but has by no means been pioneered — since 2014 when Narendra Modi assumed power at the Centre.

The two essential features of the playbook: One, make ill-concealed threats to approach the proprietors and render the journalist unemployed or ineffective. Two, use the police to harass or keep the journalist under pressure and cause a chilling effect so that the peers will think more than twice before filing reports unpalatable to the government of the day.

Take, for instance, Irani’s warning to Yadav in Amethi, delivered of course with a friendly smile. Whatever the status of Yadav (some media outlets do not give hinterland newsgatherers any identification papers), the available footage from a video of the purported incident does not show him insulting the people of the constituency but merely asking the visiting minister for a quote.

Irani’s reply suggests she is speaking to him assuming that he is a journalist. Irani not only declares without hesitation that she would speak to the “malik” but also proceeds to name the executive director of the media group. Through the public declaration, Irani, a former information and broadcasting minister, has unwittingly given an insight into how those in power operate to “reform” annoying journalists.

Once it was unthinkable for ministers to call up proprietors and complain about journalists on matters essential to discharging their responsibilities — such as asking questions. No self-respecting proprietor or editor would entertain such calls. The stock response would have been to write a formal letter, approach the Press Council of India or go to court.

But when Indira Gandhi was in power, the grapevine was rife with talk of how calls from the Prime Minister’s Office would have a say in the selection and appointment of editors.

In 1974, the dismissal of an editor kicked up such a furore that the official spokesperson for the government denied any role.

In the prevailing era of “headline management”, conventions that allowed proprietors to be dismissive of thuggish government minions, which in turn gave journalists the courage to ask uncomfortable questions, have fallen into the ever-lengthening list of endangered media practices.

A day after Irani made the comments to Yadav, some media reports suggested that he was a video journalist accompanying a Bhaskar stringer, and that the stringer had been asked to hand over his mic ID.

The Bhaskar group had been raided by the income-tax department in 2021, close on the heels of its aggressive coverage of the Covid crisis in the heartland. The coverage had then drawn international attention, much to the discomfiture of the Narendra Modi government.

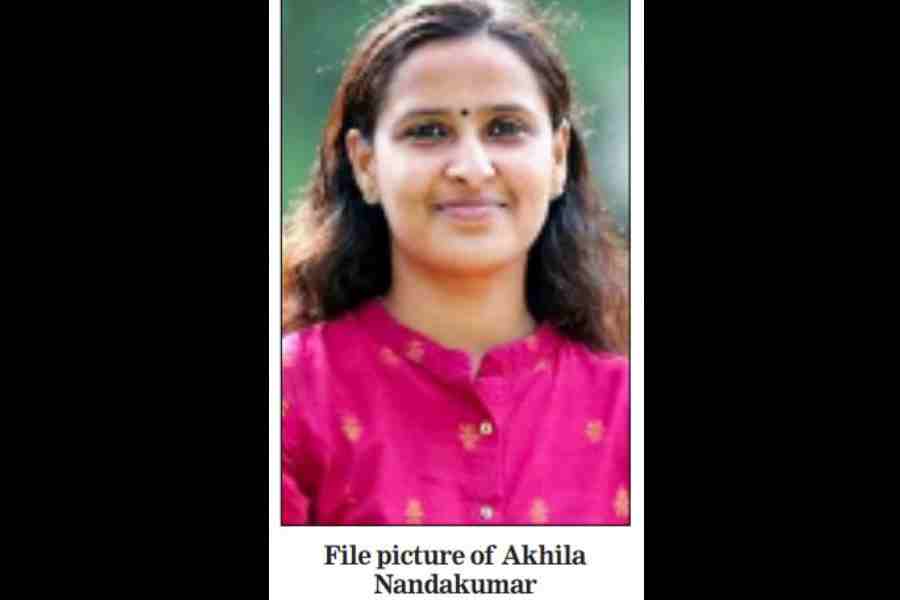

In Kerala, the case against Akhila comes at a time the CPM in the state has been accused of trying to curb media freedom, with multiple journalists being booked.

The Asianet News episode has another curious sub-text: the channel is owned by Rajeev Chandrasekhar, now a minister in the Modi government.

Some might cite poetic justice and seek vicarious pleasure in defending the police case by saying Asianet News is being paid back in the same coin that its owner’s party has minted at the Centre and in states like Uttar Pradesh.

But there’s a flip side: in the process, the Left government headed by PinarayiVijayan, who also handles the home portfolio, and the Modi government are being called two sides of the same coin.

Malayalam writer and social commentator Pramod Puzhankara cited the several cases filed against a host of journalists in northern India during the farmers’ agitation to remind the Kerala government how its case against Akhila can draw the same charges that the Left had levelled then against the Modi and Yogi Adityanath governments.

When Newsclick, the digital media outlet, was raided in 2021, the CPM had issued a statement condemning the Enforcement Directorate’s action. “The ED action is a blatant attempt to intimidate and suppress an independent news portal. Newsclick has been providing credible and wide coverage of the farmers’ protests,” the CPM had said in a statement.

The party added that central agencies are being used by the Narendra Modi government to “harass and silence independent media”.

Although some can argue that Akhila could have been more thorough while checking facts and should have taken the claims of the KSU with a pinch of salt since it is the principal rival of the SFI, many have pointed out that she had reported an allegation whose content was seen on the college’s official site. The college is a red citadel.

Puzhankara reminded the ruling Left Front and the police that the job of the media was to report even a conspiracy. “By their argument, it was a suspected conspiracy (against Arsho). If that’s the case, then the media will report such a conspiracy since that too is a story,” he told this newspaper.

“But registering a case against a reporter for a simple act of reporting a story is a mindless action. This only reflects the rationale of a totalitarian regime and how it uses state power to crush dissent, the Opposition and even the media,” said Puzhankara.

Harish Vasudevan, an advocate and a well-known commentator, was quoted as posting by Truecopy Think, a digital platform, that the police should have first approached a court and registered the case only after a magistrate passed an order.

Puzhankara drew a parallel with how the Union government had barred the screening of the two-part BBC documentary, India: The Modi Question, that examined the politician’s role in the Gujarat riots.

“The logic was that the Supreme Court has already exonerated Modi in all the cases and hence the BBC is conspiring to tarnish his image. So it was the conspiracy angle even in that case,” he said, alluding to how voices of dissent are often smothered by raising the spectre of conspiracy.

Left-leaning writer and president of the Kerala Sahithya Academy, K. Satchidanandan, described the police action as a challenge to media freedom.

“It is the natural duty of journalists to explore the factual position of a case. It is baffling to know that a journalist named Akhila Nandakumar has been booked in a case. We need to see this as a challenge to media freedom,” he told a channel on Sunday.

The Kerala Union of Working Journalists demanded the immediate withdrawal of the case against Akhila.

“This action that brings shame to Kerala should be immediately withdrawn, or else the media fraternity will launch a massive agitation,” it said.

Akhila, who is with the Kochi bureau of Asianet News, told The Telegraph on Sunday that she had gone to the Ernakulam college on Tuesday for another report on former SFI leader K. Vidya allegedly forging a teaching experience certificate of Maharaja’s College.

“That was when KSU campus unit vice-president Fazil told me there was a bigger story. I went live from the campus since the exam result (of Arsho) was there to see online,” she said. The KSU is the Kerala Students’ Union, the Congress’s campus wing.

Akhila and the others have been booked under IPC Sections 120B (criminal conspiracy), 465 (forgery), 469 (forgery to harm reputation) and 500 (defamation).

She was yet to receive a notice or a call from the police by 4.30pm on Sunday.