Several government arms had advised the Centre against challenging the Allahabad High Court judgment that caused a reduction in quota jobs for university teachers, prompting it to decide to implement the order, documents obtained by The Telegraph under the RTI Act show.

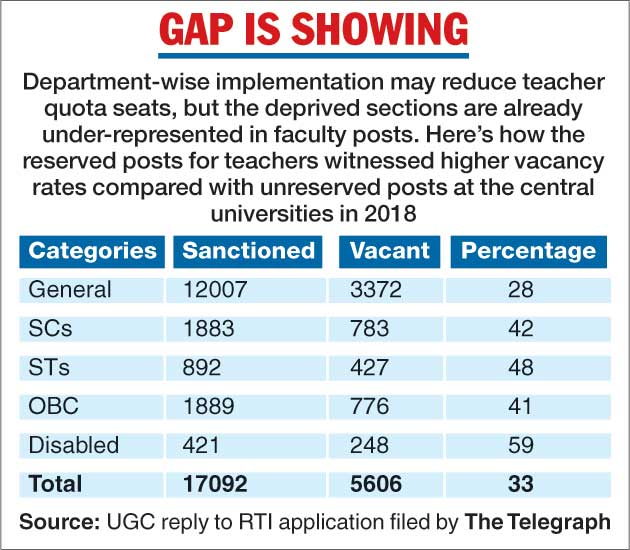

Eventually, an outcry from the deprived sections, Opposition parties, the BJP’s Dalit MPs and allies such as Ram Vilas Paswan did force the government to challenge the order with a petition, which the Supreme Court dismissed on Tuesday.

However, the RTI documents reveal that the government’s original decision to enforce the April 7, 2017, high court order was preceded by months of discussions among ministries and departments, suggesting the Centre was keenly aware of its drastic implications but chose to go ahead with it.

One suggestion, from the department of personnel and training (DoPT) to the human resource development ministry, was to examine the high court’s verbal indication about the possibility of abolishing teacher job quotas altogether. But in the end, the government ducked out of the matter.

The high court had ruled that teacher quotas should be calculated department-wise rather than by taking the whole university as a unit — as was done till then — a measure that threatened to sharply reduce the quota jobs.

On July 6, 2017, S.K. Saha, an undersecretary in the HRD ministry, sent a brief note on the matter to the DoPT for its comments.

It said the University Grants Commission had sought advice from its standing counsel, Manoj Ranjan Sinha, and was told the judgment “being just and proper, needs no interference by way of a challenge to Supreme Court”.

G. Srinivasan, a deputy secretary in the DoPT, then wrote to the ministry on August 10 that year, asking that the commission — the higher education regulator — examine a set of 10 past high court and apex court judgments cited by the high court.

In a non-binding observation, the high court had cited these judgments — some of which questioned the logic of quotas in teaching jobs — and suggested the government examine them.

The ministry forwarded the recommendation to the commission, which formed an expert panel that examined the judgments but did not take a stand. The panel, though, supported the high court order on implementation of quotas department-wise.

The then higher education secretary, K.K. Sharma, and HRD minister Prakash Javadekar asked the department of higher education to get the opinion of the law ministry and the solicitor-general too.

The law ministry asked the HRD ministry to address the issue in consultation with the DoPT, the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes. It could not be ascertained whether this was done.

But on March 6, 2018, the regulator, which functions with the HRD ministry’s approval, issued a letter to all universities to implement teacher reservation department-wise.

This led to K.P. Solanki, chairperson of the parliamentary standing committee on the welfare of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, calling a meeting of officials of the HRD and law ministries, as well as the commission and the DoPT, on March 8.

“Though the matter was explained to the chairman, he was emphatic that the revised instructions issued by MHRD/ UGC based on court directions are going to reduce the reservation/ representation of

SC/ ST in appointments to teaching posts on department/ subject wise rosters,” says a note dated March 9, 2018, and signed by Subodh Kumar Ghildiyal, then a deputy secretary in the HRD ministry.

The matter was again referred to the law ministry, which advised that a special leave petition against the high court judgment be moved in the Supreme Court.

By then, the matter had come up in Parliament, with the government coming under pressure to challenge the high court order.

The HRD ministry and the regulator filed separate petitions and froze the university recruitment processes that had started in accordance with the March 6 letter.

But the apex court dismissed the petitions on Tuesday, which means the government must implement the high court order or enact a law to bypass it. In July 2017, too, the apex court had upheld the high court judgment against a challenge from a private individual.

The Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and the Other Backward Classes have 15 per cent (one in 7), 7.5 per cent (one in 13) and 27 per cent (one in four) reservation. Clubbing all the departments of a university together during a particular round of recruitments tends to throw up a number of vacant seats large enough to allow all these percentages to be adequately implemented.

But since individual departments tend to have only a few vacant posts, such percentages result in small fractions, meaning the quota candidates lose out.

Under this system, therefore, the first three vacant posts go to non-quota candidates, the fourth to an OBC candidate, the seventh to a Dalit and the 13th to a tribal candidate — no matter how many years it takes a seventh or 13th vacancy to open up in that department.

Further, such calculations cannot happen if the department concerned has less than seven (or 13) seats.

If it has, say, only six seats, the seventh vacancy is considered the first vacancy of a new cycle — so no Dalit or tribal candidate is ever recruited to it. A department with three or fewer posts is forever closed to quota candidates.