Twelve in every 100 people older than 60 in India — and 17 in every 100 in Bengal — need supportive palliative care, mainly because of chronic respiratory disorders, stroke and cancer, the country’s first nationwide palliative care need assessment has found.

The study has revealed that chronic respiratory disorders are more likely to require palliative care than even cancer or stroke, which are widely perceived by the public as the primary conditions that lead to dependency or long-term-care needs.

Palliative care is specialised support focused on improving the quality of life for people with serious illnesses by easing pain, symptoms and emotional stress.

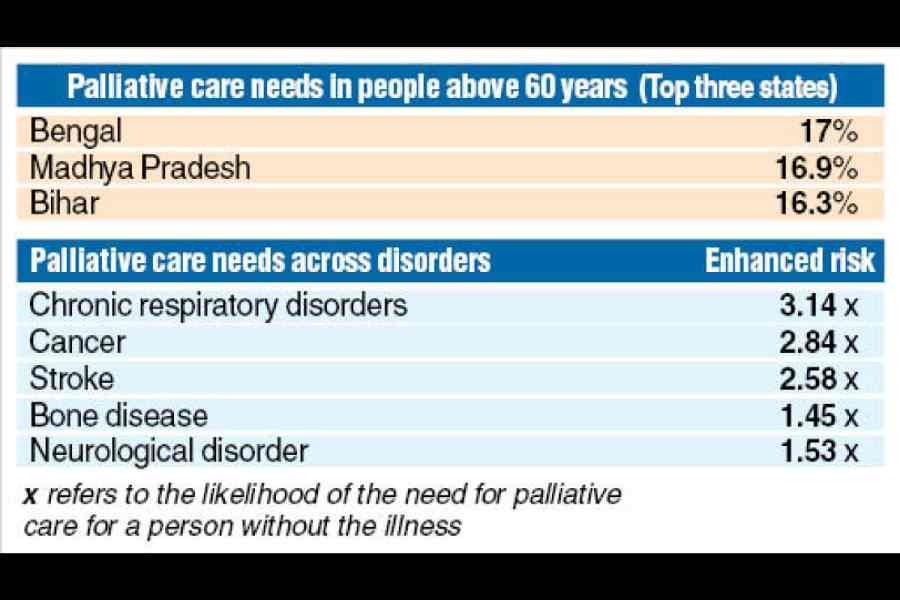

Bengal had the highest need for palliative care (for 17 per cent of people older than 60 years) followed by Madhya Pradesh (16.9 per cent), Bihar (16.3 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (15.6 per cent). The lowest levels of need were seen in Arunachal Pradesh (2.2 per cent), Nagaland (2.4 per cent) and Mizoram (3 per cent).

People with chronic respiratory diseases were about three times likelier to require palliative care compared with those without the illness; those with cancer were 2.84-fold as likely, and those who had a stroke about two-and-a-half times as likely.

“This was an unexpected result — that chronic respiratory disorders are nearly on a par with cancer or stroke,” said Terrymize Immanuel, a palliative care researcher at the SRM Institute of Science and Technology School of Public Health in Chennai, the study’s first author.

“This finding underlines the importance of enhancing awareness among the general public and healthcare workers who typically assume that palliative care is needed by those affected by cancer or stroke,” Immanuel told The Telegraph.

The study, just published in the journal BMC Palliative Care, has estimated that 12.2 per cent of people above 60 years require palliative care at the national level. For those over the age of 70, the figure rises to 18 in every 100.

“We’ve tried to assess the demand for palliative care at a time India’s 60-plus population is growing and the incidence of non-communicable diseases is also rising,” said M. Benson Thomas, a health economist and associate professor at the SRM School of Public Health.

India’s population of people aged 60 or above is expected to grow from 15.3 crore in 2022 to 34.7 crore by 2050.

The researchers say national and state assessments are important to guide government or private initiatives on palliative care. “This study fills many gaps in the available data,” said Roop Gursahani, a senior neurologist at the Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai, and a study co-author.

“Palliative care has been a challenging issue marked by low demand and low supply,” Gursahani said. “Much of the focus has been on palliative care for cancer patients. But palliative care for disorders such as dementia, Parkinson’s disease, or stroke with possibly longer survival times can be difficult, involving decisions such as whether to admit a patient to an intensive care unit or whether to initiate artificial feeding.”

The SRM team and collaborators used data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study of India (Lasi), a research initiative designed to track the health of a large sample of people aged 45 years or older from across the country for multiple years. Lasi is a collaborative effort of the Union health ministry, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the University of Southern California.

For the palliative care analysis, the researchers selected a sample of 27,450 people aged 60 years or older and determined what proportion among them met the criteria for palliative care. Examples of such criteria include a person confined to a bed or a chair for over 12 hours, a person dependent on others for daily self-care requirements, a person experiencing progressive weight loss, persistent fluid retention, or progressive illness with growing complications and unplanned hospital visits.

Twelve in every 100 people in the sample met at least two such criteria. The study found no significant differences in the palliative care needs between different economic categories of households in the sample. But Muslims had a higher need (15 per cent), compared to Hindus (11 per cent) or Christians (8 per cent).

“We’ll need more research to understand the geographic patterns of palliative care needs,” Immanuel said. “Why is the need for palliative care low in the Northeast? Is Bengal’s large need related to the state’s high incidence of stroke? Why do we see differences in palliative care needs across religions? These are open questions.”