As the trapped workers came out of the under-construction road tunnel after 17 days, the happy end to a rescue effort that had riveted India set off celebrations across the country.

Gone for the moment were questions about why the 41 men had been put at risk of being entombed in the tunnel in the first place. Instead, television crews outdid one another in excitement and volume, showering praise on the officials involved in the rescue, who lined up on Tuesday with garlands for the workers. Cameras focused on local representatives of the BJP, who credited the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“Modi makes it possible!” they chanted in Hindi.

While activists and environmentalists also watched with relief, the scenes carried another, very different meaning for them. They had long warned, in futile court cases and failed tribunal hearings, that the $1.5-billion road-widening project was dangerously destabilising the already fragile Himalayan landscape. To them, the fact that the work had proceeded anyway, ultimately incurring a disastrous landslide, was another reminder of how Modi has removed almost every obstacle to getting his way.

“The focus is on rescue and not the reasons thereof,” said Mallika Bhanot, an environmental conservationist in Uttarakhand, the state that is the site of the tunnel. “They do not want to bring attention to it.”

The construction project, which is largely widening more than 800km of roads to connect four major stops of the Char Dham pilgrimage route, brings together two pillars of the image Modi has built: as an ambitious infrastructure developer and a champion of Hindu interests.

The Prime Minister personally inaugurated the highway project in 2016. In front of tens of thousands of people, Modi said the improved highways would make travel between the pilgrimage sites so easy that “people will remember the work that has been through the project for the next 100 years”.

The Prime Minister dedicated it “to all those who had been killed in the 2013 Kedarnath tragedy” when flash floods killed more than 6,000 people in the state — unintentionally pointing to an example of the increased risk of natural disasters in the Himalayas as the planet warms.

Modi is credited with increasing investment in India’s infrastructure. But in the case of the highway project, activists and scientists say his government simply bulldozed through their concerns.

The ministry of road transport and highways, reached for comment on Wednesday, asked that questions be sent in writing but did not immediately respond once they were submitted.

It remains unclear whether additional checks, or a less ambitious programme, would have been able to prevent the landslide that trapped the workers in Uttarakhand.

In 2018, a citizens’ group appealed to the National Green Tribunal, asking for the work to be stopped because no environmental impact assessment had been done. Widening the road would be impossible without increasing the risk of disaster, the group argued, and the project would require removing tens of thousands of trees.

The tribunal ruled that it had little power to act. The government had chopped up the project into 53 pieces, each under the 100km requirement for mandatory environmental impact assessments.

When the group escalated its complaint to the Supreme Court, the judges in 2019 ordered the government to convene an expert committee to assess the project and its impact on the Himalayan landscape, and to offer advice on how to proceed.

The committee, headed by environmentalist Ravi Chopra, found that the project had already damaged the Himalayan ecosystem because of “unscientific and unplanned execution”.

Its assessments from trips to the site found that hillside cutting had been preferred over less harmful approaches. The panel found that more than half of the new slopes were disaster-prone, and that dozens of slope failures had already taken place. The project had also not planned properly for waste disposal, threatening the flow of natural streams.

A majority of the committee members, many of them government officials, approved of the government’s road-widening plan anyway. A minority, including Chopra, said the government had breached its own guidelines limiting the width of roads in hilly areas to reduce ecological damage.

The court sided with the minority opinion and ruled in September 2020 that the road be built at the narrower width.

But for months, work continued unchanged. Chopra wrote letter after letter to the court, complaining that the government was not complying with its orders.

The government then amended the guidelines for road construction, working in an exception: Regions of strategic interest were exempt. Then it went back to the court with a new argument focusing on national security.

The government said that the roads in question were important for ferrying military goods to the border with China, even though the army chief had said that the narrower width was not an issue for the military, and that the advantage gained for defence-readiness from wider roads could be lost to an increased risk of landslides.

In December 2021, the court changed its order, allowing the government to continue with the wider road.

Chopra resigned later.

“During the period of that one year, the government was simply not willing to listen,” he said. “They were in a rush to complete the job, they were on a very tight deadline, they were taking shortcuts. So disasters were inevitable.”

In 2022, an Opposition leader in Parliament asked roads minister Nitin Gadkari if the project, billed as one giant initiative, had been divided into many segments, and if that was to get around an environmental impact assessment. Gadkari confirmed the project had been divided into 53 segments. His answer to the next part was more telling. “Does not arise.”

New York Times News Service

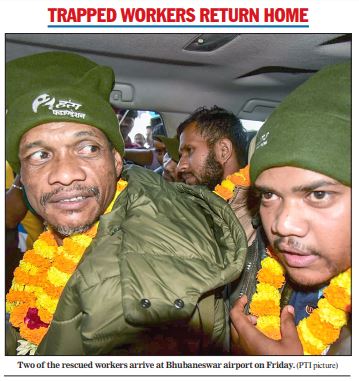

A narrow mountain stream from where water trickled into the chamber of the Uttarkashi tunnel in which the 41 labourers were trapped served as their source of water during the 16 days of confinement, some of the workers said on Friday. Ram Milan, one of the eight labourers from Uttar Pradesh who was brought to Lucknow in a bus from Rishikesh after being released from hospital, told reporters: “There was a source among the mountain rocks from which water falls slowly and constantly inside the tunnel, a little distance from where we were huddled together after getting trapped following the collapse. We had a jeep with us and some big plastic bottles of 10 and 20 litres in which we used to collect water for drinking. Each bottle used to get filled in about an hour. Manjeet Kumar, another of the labourers, said the space within which they were trapped was about 240 metres long, beyond which there was a stretch of unfinished road with gaping holes, and after that a small stretch of finished road. The source of water was beside that stretch of finished road. “We filled the holes with earth and concrete so we could walk or take the jeep to that part to collect water,” Manjeet said. In Lucknow, the eight labourers met Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath and narrated their experiences of remaining trapped inside the tunnel for about 400 hours. In Bihar, five labourers landed at Patna to a rousing welcome. “There would have been no need for us to go to other states to work had the Bihar government provided us work,” Sonu Kumar Sah of Saran, one of the trapped labourers, said. In Bhubaneswar, Odisha government officials and relatives received four workers who had been trapped in the Silkyara tunnel. “It was tough for us. For the first 10 to 12 hours, there was fear, frustration and anxiety. But over the next few days, we overcame it by supporting each other,” Dhiren Nayak said.