The nation witnessed from Ayodhya on Wednesday the ritual merger of Church and State — rishi and raja — as Prime Minister Narendra Modi, elected head of a constitutionally secular state, turned de facto mahant to perform the ground-breaking rites of the Ram temple and declared all of India “Ram-maya”, or suffused with Ram.

There lay resonance and recall with some of what transpired on Wednesday to an incident from India’s infancy as a modern nation. When the Somnath Temple — repeatedly ransacked by Mahmud of Ghazni in the eleventh century — had been restored and awaited re-opening in 1951, the then President Dr Rajendra Prasad was keen on attending. He also had a vocal supporter in K.M. Munshi, then the Union minister for food and agriculture.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, overtly detested by the current establishment, made it plain he did not want Dr Rajendra Prasad to visit Somnath on the ground that religion should be separated from public life. Dr Rajendra Prasad proceeded to Somnath irrespective.

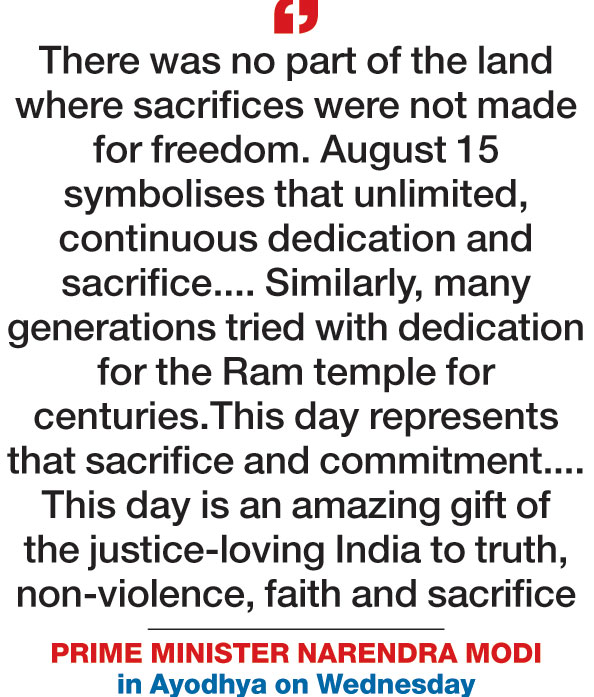

Turned out in the mien and hues of a sadhu, Modi spoke with no ambiguity that in his imagination and his scheme, the Ayodhya event had finally embossed India as a Hindu country and him as its itinerant poster-boy.

Truth to tell, television footage of Wednesday’s theatre might leave a few confused about whose deification it was really about.

The opening of a “new history”, Modi called it, an opening whose tone was consciously majoritarian and exclusionist of India’s pluralities.

“This is an end to hundreds of years of waiting,” he proclaimed. “A day just like August 15 when we pronounce once again the end of our slavery. The trumpet of this victory is echoing across the world. My profuse congratulations to all bhakts and Ram bhakts. All of India, all of its 1.3 billion people, have become Ram-maya.”

He spoke as if oblivious, or defiant, to the truth that a fifth of India’s population, whom he also leads as Prime Minister, isn’t Hindu and Ram is not the deity of their denominations.

He spoke, too, from precincts that are still the subject of criminal conspiracy proceedings in the CBI court of Lucknow. It is a case that concerns the riotous tearing down of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992.

Among the chief accused are members of the “margdarshak mandal” of Modi’s party — Lal Krishna Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi, lead actors of the volatile Ramjanmabhoomi movement whose valedictory celebrations were opened on Wednesday.

Neither was sought out to be present on the occasion. The star of it was Narendra Modi, the man who played dutiful major domo to the crusades Advani triggered following the Palampur Resolution of 1989, which made the construction of a Ram temple at the site of the Babri Masjid the arrowhead of the BJP’s objectives.

The Advani-led “Ram rath” campaigns swelled the BJP’s popularity but left the nation riven and incensed along barbed communal fences as never after the Partition. Thousands were killed in flashpoints that opened in the wake of Advani’s yatras, or were sparked by its flaming temper.

Hinduism acquired the menace-edge and militancy of Hindutva, the kindly greeting of “Jai Siya Ram” morphed into the “Jai Shri Ram” war cry.

It inaugurated a seminal moment in a secular nation’s lives and times. It shook the belief systems of society and politics; it echoed belligerently from the legislatures to the courthouses; it rent India’s streets bloodied, its populace rekindled with medieval bitterness and loathing.

The day the cynically gathered mob at Ayodhya razed the Babri Masjid, in brazen violation of political pledge and underwritten guarantees to the Supreme Court, many deemed it the nation’s second Partition.

That divisive push across India Modi on Wednesday called a “pavitra andolan” (pure movement) for the nation to applaud and acclaim. It was as a consequence of that “pavitra andolan” that another “swarna yug”, or golden age, was about to embrace India.

That movement — the Ramjanmabhoomi movement — he also blithely likened to the independence movement led by Mahatma Gandhi. He omitted to mention that Gandhi’s was a painstakingly inclusive mission that brought all manner of Indians together to the common purpose of sending off an imperial regime.

Or could he have been signalling to his constituency a depth-charge of a message? That the similarity with Gandhi’s independence movement also lies in the truth of it culminating in a “partition”?

Some of the imagery Modi employed were trademark quivers from his playbook, the code he practices fully aware that his votaries will decipher it. He spoke multiple times, for instance, of this day being a day of “freedom from slavery”. It cannot be lost on many what slavery he was alluding to and what the freedom was from; where he stood and what he was there for clarified it all.

Bluntly put, he was speaking of freedom from the debris of the decimation of the Babri Masjid, and the metaphors it conjures and translates into. He was speaking of freedom from the slavery of what India, in the letter and spirit of its adopted Constitution, set out to cherish.