The Union cabinet on Monday gave the go-ahead for a legislation to give 10 per cent quota in state jobs and educational institutions for 'economically weaker sections'.

The proposed criteria for determining which families would qualify for the “economically weaker” tag are as follows: an annual income below Rs 8 lakh; farmland less than 5 acres; residential house below 1,000sqft; residential plot below 100 square yards in a notified municipality; residential plot below 200 square yards in a non-notified municipality area.

Apart from triggering protests by the Congress and other Opposition parties, the Constitution (124th Amendment) Bill, 2019, has raised several questions on what the legislation entails and who exactly would benefit from it. We answer some of them.

How many people are expected to be covered by the economic quota?

No clear estimate is available. The government has captured economic data of 25 crore households under different criteria as part of the Socio Economic Caste Census (SECC) 2011-12. But caste-based data have not been published. The income tax department has data on those filing returns. However, they do not segregate the tax payers in social categories.

The NSSO does collect consumer expenditure of sample households which can be extrapolated to reach an estimate on individual household income. However, the NSSO maintains data under Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Others categories. It does not differentiate between Other Backward Classes and unreserved groups.

Isn’t the annual income ceiling of Rs 8 lakh for a family too high? Doesn’t it work against the poorer people who will have to compete with families earning as much as Rs 66,000 a month?

Yes, that’s the point raised by several parties on Tuesday when trade unions observed a general strike for a guaranteed minimum wage of Rs 18,000 a month. Also, anyone with an annual income of more than Rs 2.5 lakh comes under the income tax bracket. On social media, many asked, partly in jest, why the exemption limit too should not be raised.

Is there a perception that Brahmins and other historically privileged castes stand to gain more than the others in the 10 per cent quota?

Yes. It is an assumption based on perceptions. Only eventual empirical data will be able to establish it. The fundamental reason for such an assumption is that Brahmins have historically enjoyed better access to education. Compared with a first-generation or second-generation educated aspirant from, say an upper caste closely tied to farming, a Brahmin candidate can expect to score higher marks. The point to remember is that the upper castes include diverse castes with wide variations in their socio-economic background. The 10 per cent blanket quota need not mean a level playing field for all upper castes.

The OBCs and the Dalits are demanding a larger percentage of quotas? What is their logic?

It has been their long-standing demand for quotas in proportion to their population. According to the 1931 caste census, OBCs constituted 52 per cent of undivided India’s population. The government has not yet made public the caste census carried out in 2011-12.

Does the 10 per cent quota cover private education institutions?

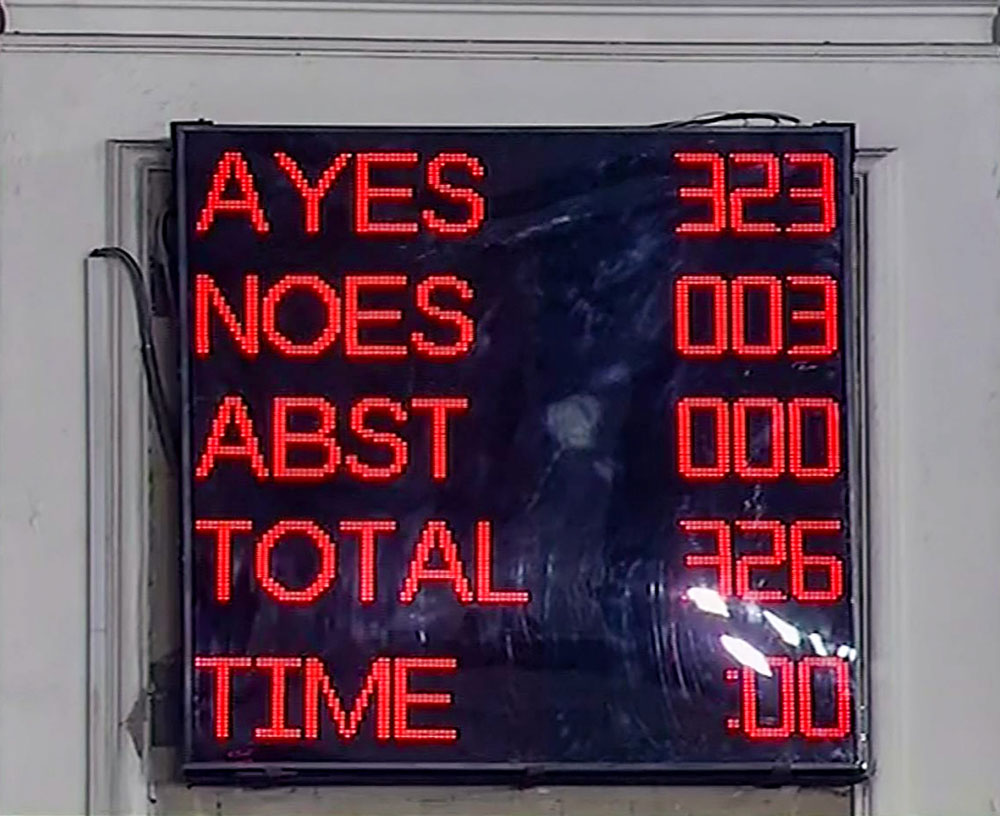

The bill has language that suggests so but the quota in private institutes has not crossed the last mile yet. The Constitution has an enabling provision for quotas in private educational institutions but a separate law needs to be enacted for this. The bill passed in the Lok Sabha on Tuesday reflects this phraseology. But a separate law needs to be passed for the private sector quota to kick in. The Right to Education Act does reserve a certain percentage of seats for poor students in schools but that is at the entry level.