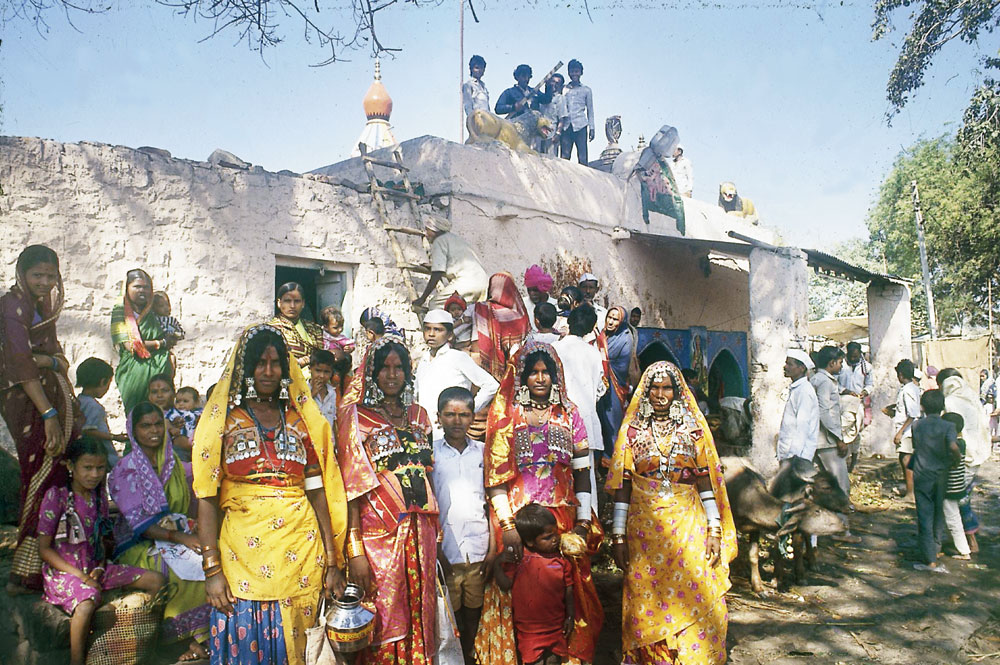

A Lodha family in a village in Panipat, Haryana (Ramakant Kushwaha)

Dakxin Bajrange was a young playwright in Ahmedabad when radical writer and activist Mahasweta Devi asked him to take up the fight of the denotified tribes, or DNTs, through theatre. “That was exactly 20 years ago. I, in fact, didn’t know what this term meant even though I belonged to the Chhara tribe, a DNT community,” he says.

It is estimated that there are around 200 denotified tribes and several hundred nomadic tribes in India. Some of the major ones include the Chharas, Sansis, Banjaras, Nats, Pardhis, Wadars, Bedars, Lodhas and Gowlis. These tribes were designated criminal tribes and codified as such through a law passed by the British in 1871. The law was struck down or denotified in 1952, but the name stuck.

Bajrange talks about how the late Mahasweta Devi, whom he refers to as Amma, had already been fighting for the rights of denotified tribals for a long time when he met her. She wanted others to join this fight.

“Amma wanted all of us to reach more people through theatre and assure them that DNTs are not second-class citizens, that there is no shame in being born into these communities,” he says. He recalls how Mahasweta Devi set up Budhan Theatre in Ahmedabad. She named it after a man from the denotified Sabar tribe in West Bengal who was killed in police custody in 1994.

Today, Bajrange and other like-minded individuals from all over the country have come together to form the National Alliance Group (NAG) for DNTs. They are hoping that the spark Mahasweta Devi lit two decades ago will become a raging fire in the coming months and years.

The NAG formed in 2014 has a many-pronged strategy. Its concerns are social, developmental, cultural and even literary. But what is new and throbbing is its current political zeal.

The success of Patidar leader Hardik Patel, Dalit activist Jignesh Mevani and OBC leader Alpesh Thakor in Gujarat as effective political voices has strengthened the belief of the NAG’s constituent groups that they can take on the political establishment if they join hands.

“We have to fight as we have nothing to lose. It is as simple as that,” says Bharat Vitkar, a Pune-based rights activist and a member of NAG.

Even now, DNTs remain a neglected lot despite the fact that they constitute 7 to 10 per cent of India’s population. They may no longer be

designated as criminal tribes but in police records, community members continue to be treated as such. Many, in fact, don’t even want to be identified as belonging to a denotified tribe because of this.

In 2003, the central government appointed a separate national commission for nomadic, denotified and semi-nomadic tribes; it was reconstituted in 2005 under the chairmanship of Balkrishna Renke. The reconstituted commission, known as the Renke Commission, was meant to study the various communities and come up with recommendations for their uplift. When it submitted its report in 2008, however, its findings shocked the country.

It revealed how so many years after Independence, these tribes continue to fare poorly be it in literacy, housing, employment or living conditions. It also revealed that 89 per cent of the denotified communities and 98 per cent of the nomadic and semi-nomadic communities reported that they did not own any land.

“They are probably worse off than scheduled tribes,” says Vitkar, who is organising the denotified and nomadic tribes in Maharashtra. He adds, “The findings were shocking even for activists like me working in the field for many years.”

Some of the major recommendations of the Renke Commission included a separate finance and development corporation for DNTs, like the National Scheduled Castes Finance & Development Corporation; a separate department for the welfare of DNTs at the state and central levels; that the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 be made applicable to DNTs and that constitutional amendments be made to reserve seats for them in state Assemblies.

These demands are now on the agenda of the NAG. Says Bajrange, “We have had two commissions so far. The Renke Commission, which was pathbreaking, and more recently the Idate Commission. But nobody knows whether the governments have accepted or rejected these reports. What we now want is action on the ground.”

Numbers notwithstanding, DNTs have never come together before as a pressure group to play a political role. There is a reason for this, argue experts who have studied DNTs for decades.

“The Indian Constitution does not officially recognise the DNT and nomadic communities as distinct (categories) and hence they don’t have the social and economic protection that Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes enjoy in the country,” says Chandrakant Puri, who is a professor at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Contemporary Studies at the University of Mumbai. “Politically, they have remained on the margins,” adds the DNT expert.

Now that the task of uniting several organisations has been achieved with NAG, the next step is to chalk out political action.

As the clock ticks away on the Lok Sabha elections, NAG members pore over Lok Sabha constituencies, assessing the strength of these tribes in each constituency and zeroing in on those where they think they can make a difference.

“We are there in very good numbers in states such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. We can influence elections like any dominant caste group,” says Mohammed Kalam, a Patna-based activist who is fighting for the Nat community in the state. “But only if we act unitedly. If we cannot, our condition will not improve in another 70 years,” he warns.

It is not that DNTs and nomadic tribes have not fought back for their rights at all, but those battles have been few and far between. Some like the Vadda or Vaddars in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are politically strong because of their long struggle for recognition. The most recent example is of the Bhar community, a denotified tribe, in north India.

The Bhars have come to the political fore in Uttar Pradesh under the Suheldev Bharatiya Samaj Party (SBSP). Suheldev is said to have been an 11th century king who fought Muslim invaders. The SBSP chief, Om Prakash Rajbhar, is a minister in the Yogi Adityanath government.

Says Rahul Rajbhar, a Varanasi-based activist of the Bhar community, “The party has been successful in building a narrative around self-pride keeping Suheldev and his exploits in front. Now people from our community tell me how police don’t harass them and there is new-found respect.”

But the problem, according to Rahul Rajbhar, is this. Parties such as the SBSP talk about their own communities, in this case, the Bhars. But what the denotified and nomadic tribes need is

a larger identity. “We have never had radical leaders like B.R. Ambedkar for the Scheduled Castes or Birsa Munda for the tribals. We always needed somebody we could identify as a unifying leader of our communities spread across the country,” he says.

But Bajrange and his ilk don’t launch verbal fusillades against either the police, politicians

or other castes, they work quietly. When you point that out, the response is that the job at hand right now is to infuse confidence into a section that is still unaware of its own strength. “DNTs are suspicious by nature and they are not comfortable picking fights because of past police oppression,” Kalam says.

But some changes are visible on the ground. “I notice that rallies of DNTs in Gujarat and Maharashtra are attracting tens of thousands of people. We could never imagine such a situation,” says Vitkar.

The political ideology of these groups is yet to take shape, but most leaders of NAG like Bajrange, Kalam and Rahul Rajbhar would like to ally with “secular” forces. Vitkar, however, espouses an open mind.

Puri feels these groups shouldn’t worry about political ideology, at least not until they become “strong” on the ground. “These people have their political leanings, but those shouldn’t be a distraction. Where they can unite is on the goals of the DNTs,” says Puri, who has drawn up a 26-point agenda on which the DNTs are being implored to unite.

Says Bajrange, “We have to come together and fight, only then will the political parties listen to us. That will be the best tribute to Amma.”