The year, 2019, will be remembered in Kashmir for the abrogation of Article 370, detention of three former chief ministers of the state and the subsequent clampdown, communication and internet blockade that disconnected seven million people of the valley from each other and from the world outside.

After the BJP government revoked Article 370 and divided the state into two Union Territories on August 5, the state enforced a total communication blackout in the region, snapping telephone services, including mobile and broadband internet. Although the ban on postpaid mobile network was lifted after over two months on October 14, prepaid phones, SMS and internet services remain banned for more than four months and counting.

The communication blackout created an information black hole in Kashmir. The local press bore the brunt of the blockade. It’s functioning was crippled. Its coverage of how the clampdown affected people’s lives was severely curtailed or suppressed.

After August 5, all prominent local dailies started publishing fewer print copies, with barely four to eight pages. Distribution was also limited due to the shutdown and restrictions imposed by the government. The ban on landline telephones, which was lifted in phases only after a month or so, and mobile telephony, including leased line and broadband internet connections at local newspaper offices, further curbed news gathering activities. Flow of information from the districts was choked as editors and their correspondents were cut-off form each other.

In the initial weeks of the clampdown and restrictions imposed after the revocation of Article 370, publication of local newspapers had to be suspended for several days. None of the prominent English and Urdu dailies of Kashmir could publish for five days from August 12.

Edit page without opinion

What got published in prominent local English dailies was a reflection of the censorship and government pressure on the press. For example, Greater Kashmir, the largest circulated daily published from Kashmir, avoided publishing editorials on the emerging situation for months after August 5 when the government revoked the special status and bifurcated the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union Territories. There was little or no coverage of how people suffered in the weeks after the communication blockade and clampdown was imposed. Its edit page did not carry opinion pieces on the situation in Kashmir post-August 5. In fact, the paper was published without an editorial page for several days.

Since then Greater Kashmir has not published a single opinion piece in its edit page on the revocation of Article 370 and the subsequent clampdown in the valley. The only opinion piece it did publish, in the third week of the clampdown, argued, curiously, in favor of the revocation of the special status.

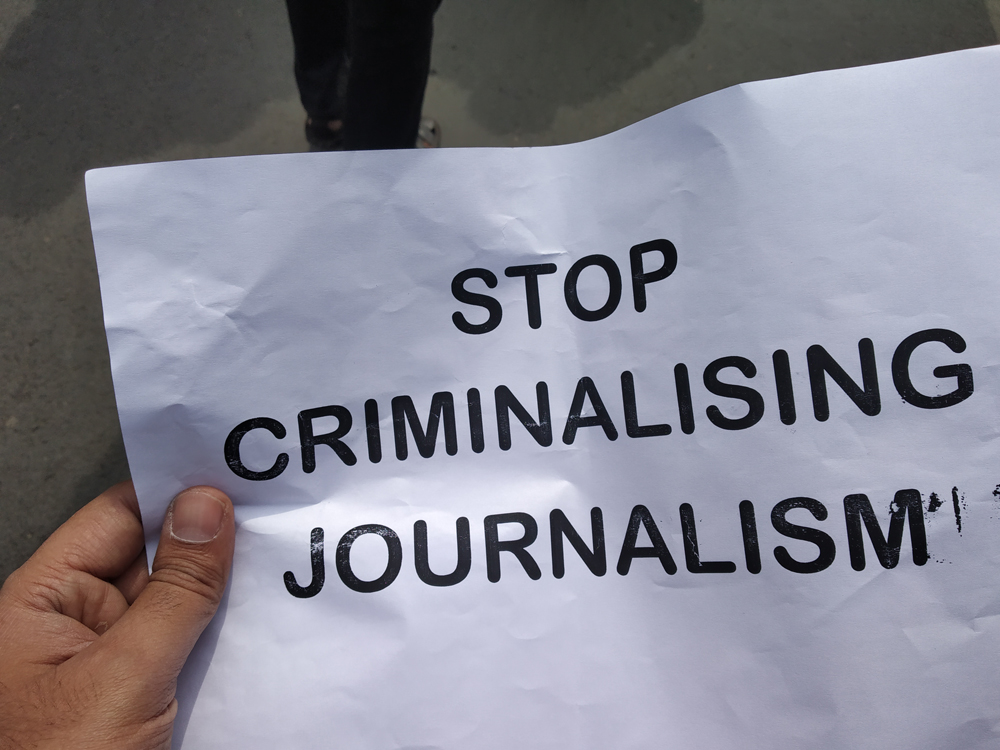

A placard carried by a journalist during the protest jointly organised by 11 journalist bodies (Telegraph photo)

Apart from that day, leading articles, columns and editorials steered clear of commenting on the clampdown and the humanitarian crisis in the valley because of the communications shutdown. Instead it wrote and commented on “The Subtle Secrets of Nature (August 9), “Vistas’s of Botox Therapy in Medicine (August 17), “Macbeth and the Moral Universe (August 22), and “Poetry and Journalism” (August 23).

Big Brother diktats

Other prominent dailies of Kashmir also adopted a soft editorial line post-August 5. There were no reports on the effects of the total communication shutdown on everyday lives of people, arrests of thousands of local youths, torture of youths in southern Kashmir, crippling of healthcare and other emergency services. The front pages carried reports based on the government version of events culled from official press releases.

What was not covered in the local press said a lot about the curtailment of the freedom of the press. The editor of a prominent local daily said the clampdown was also meant for local journalists, who were prevented from adhering to an independent line while covering Kashmir post- August 5.

He said a senior police officer visited his newspaper office in August after a photo essay on the ground situation in Kashmir had been published. The officer then went on to advise editors against publishing such photo features. After that “reprimand”, no prominent English daily published photo essays on life in he valley.

Online editions of most local dailies remained suspended for more than three months since August 5 after internet services were snapped across the valley. Only one local daily, Kashmir Monitor, updated its web edition by accessing the internet from outside the state.

No internet at Press Club

The authorities also snapped the broadband internet connection at Kashmir Press Club on August 5. This move meant that the over 200 club members belonging to the local journalists’ fraternity could not file their reports.

Later, limited internet facility was provided at a makeshift media centre set up by the government information department in a Srinagar hotel. The media centre was then moved to two small rooms of the information department where hundreds of journalists had to jostle for space to get a few minutes of internet access.

Internet facilities remain inadequate for hundreds of journalists and district reporters who can’t make it to the centre every day.

“I haven’t been able to call officials and/or sources for months. At the media centre we had to wait in queues for long simply to mail our stories,” said a local journalist. “It’s frustrating and humiliating. It is very difficult to continue working in these circumstances.”

Another local journalist said how many like him had been forced to travel out of Kashmir (New Delhi) frequently to access the internet and continue filing stories. Other Kashmir journalists, working for Delhi-based papers and magazines, had to send their stories in pen drives via a friendly face or acquaintance traveling to New Delhi.

Kashmir Press Club’s elected board raised the issue of the communications gag with the government on several occasions, urging it to restore internet for journalists and media outlets, including newspaper offices and the club. “But all these efforts have proved to be futile as these services have not been restored to journalists for four months now,” according to a statement issued by the club last month.

Journalists intimidated

At times, the authorities also resorted to intimidation. On the night of August 14, Irfan Malik, a reporter with Greater Kashmir, was picked up by police from his home in South Kashmir’s Tral district and locked up in a local police station. After his arrest created a furore, he was released on August 17. No reason was given for his arrest.

On August 31, Journalist and political analyst Gowhar Geelani was stopped at New Delhi airport before he could board a flight. He was traveling to Germany to attend a conference.

A few months ago, senior journalist and editor of an Urdu newspaper Ghulam Jeelani Qadri (62) was detained by police after he was picked up from his residence in Srinagar soon after he’d returned from office in the evening. Qadri was arrested in connection with a case dating back to 1992. He was released on bail the next day following a court appearance.

Another Kashmiri journalist, Asif Sultan, remains in detention since August 2018. He’d written a story for a local magazine on militant commander Burhan Wani who was killed in an encounter on July 8, 2016.

Kashmiri journalists protesting outside press club in Srinagar (Telegraph photo)

Intelligence agencies and police have summoned and questioned several other journalists about the source of reports filed after August 5. This has created an atmosphere of fear among local reporters and editors.

“Troubled silence”

According to a report titled, “Kashmir’s Information Blockade” released on September 4 by the Network of Women in Media, India (NWMI) and the Free Speech Collective (FSC), the continued communication shutdown in Kashmir has resulted in “throttling of independent media”.

The two-member team from NWMI and FSC spent five days in Kashmir (from August 30 and September 3) to determine the impact of the communications crackdown on the media in Kashmir. The team spoke to more than 70 journalists, correspondents and editors of newspapers and news websites in Srinagar and South Kashmir, including members of the local administration and citizens.

“Our examination revealed a grim and despairing picture of the media in Kashmir, fighting for survival against the most incredible of odds, as it works in the shadow of security forces in one of the most highly militarized zones of the world and a myriad government controls,” the report said.

“The team observed a high degree of surveillance, informal ‘investigations’ and even arrest of journalists who publish reports considered adverse to the government or security forces; controls on the facilities available for print publication, government advertising to select publications, restrictions on mobility in select areas including hospitals and the most crippling communications shutdown of all time. Significantly, there is no official curfew, no official notification for the shutdown,” the report noted.

Free flow of information has been blocked and journalists continue to face severe restrictions in all processes of news gathering, verification and dissemination, according to the report, leaving behind “a troubled silence that bodes ill for freedom of expression and media freedom.”

As Kashmir looks at the New Year, both broadband and mobile internet and the entire social media network, which was also useful for local journalists for newsgathering, continues to remain blocked for about five months now.