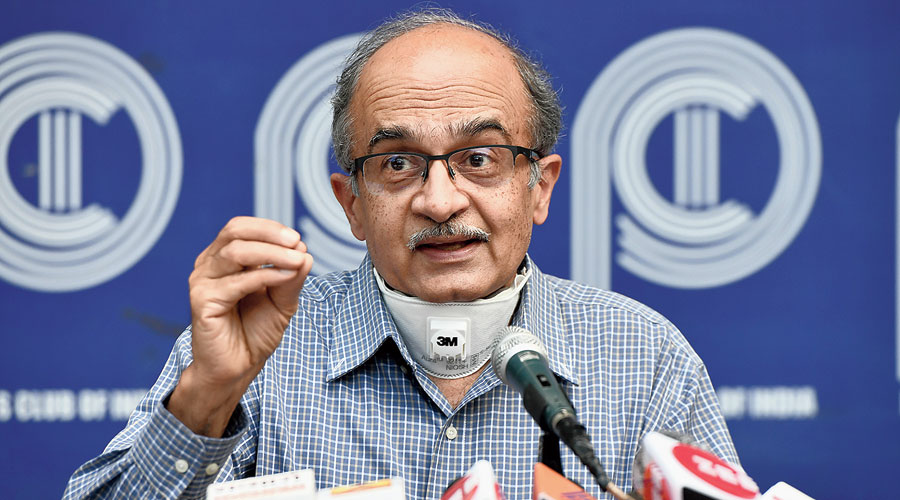

Lawyer Prashant Bhushan on Saturday urged the Supreme Court to lay down a law that anyone convicted by it of criminal contempt has a mandatory right to appeal the verdict.

He cited the “unavoidable conflict of interest involved” in criminal contempt proceedings and argued that such a right would go some way in reducing the “chances of arbitrary, vengeful and high-handed decisions”.

Also, withholding such a right amounts to violation of the fundamental rights under Articles 14 (equality), 19 (free speech) and 21 (life and liberty), Bhushan argued in his writ petition, filed through advocate Kamini Jaiswal.

The petition is expected to come up for hearing next week.

The apex court had last month convicted Bhushan of criminal contempt and fined him a token Re 1 over two tweets relating to Chief Justices of India past and present. The court is hearing another contempt case against Bhushan stemming from a 2009 interview.

Since the Supreme Court is the highest court, a person it convicts of any offence has no right of appeal except for filing a review petition – an avenue that has historically had a less than 0.1 per cent success rate.

Bhushan has sought an automatic right of appeal in criminal contempt cases. Alternatively, he has pleaded that the review petitions — which are decided inside closed judges’ chambers without the presence of counsel or litigant — be heard in open court in criminal contempt cases so that the advocates can advance their arguments freely.

Bhushan’s plea for the right of appeal relates only to contempt cases where the apex court conducts the “original proceedings” rather than hearing appeals, as it does in all other criminal cases.

“The petitioner is filing this writ petition in order to bring important procedural safeguards when this Hon’ble Court considers cases of criminal contempt in original proceedings, i.e. those proceedings where this Hon’ble Court does not act as an appellate court,” the petition says.

“In such cases, considering the fact that there is inherent unavoidable conflict of interest involved, and the fact that liberty of the alleged contemnor is at stake, it is of utmost importance that certain basic safeguards are designed which would reduce (though not obviate) chances of arbitrary, vengeful and high-handed decisions.

“It is extremely important to minimise such decisions since they not only cause great injustice to the alleged contemnor, but also bring disrepute to the court itself and are likely to be harshly judged by legal historians.”

Some of the reasons Bhushan has offered in support of his plea:

⚫ The right to appeal against conviction in original criminal cases is a right under Article 21, as affirmed in multiple apex court judgments.

⚫ Under Article 14(5) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which India has ratified, the first appeal is a right even when the trial was held by the highest court and a review is not a substitute.

⚫ In contempt proceedings, the injured party (court) acts as prosecutor, witness and judge, raising fears of inherent bias and necessitating a provision for intra-court appeal.

⚫ Contempt proceedings are quasi-criminal, so procedural safeguards similar to those observed during criminal trials must apply.

⚫ The freedom of speech can only be restricted or regulated under Article 19(2) by a procedure that is reasonable and stands the test of Articles 14 and 21.

⚫ Original criminal contempt cases form a unique category. In a concession to extraordinary circumstances, the apex court has in the past framed special rules relating to the death penalty and devised the special remedy of a curative petition against a final judgment on certain limited grounds.

⚫ Section 13(b) of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, provides for truth as a defence. It’s possible that a “truth” not accepted by one bench may be accepted by a different or larger bench or a different court when the entire matter is re-examined after a period of time.

⚫ It’s discriminatory that someone convicted of criminal contempt by a high court has the right of appeal but one convicted by the Supreme Court hasn’t.

⚫ Neither the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, nor the Rules to Regulate the Proceedings for Contempt of the Supreme Court prohibit what the petitioner is seeking.