Driven all his life by the desire to be the Prime Minister, the executive head of the government, he became the President of India, the ceremonial head who barely has any power.

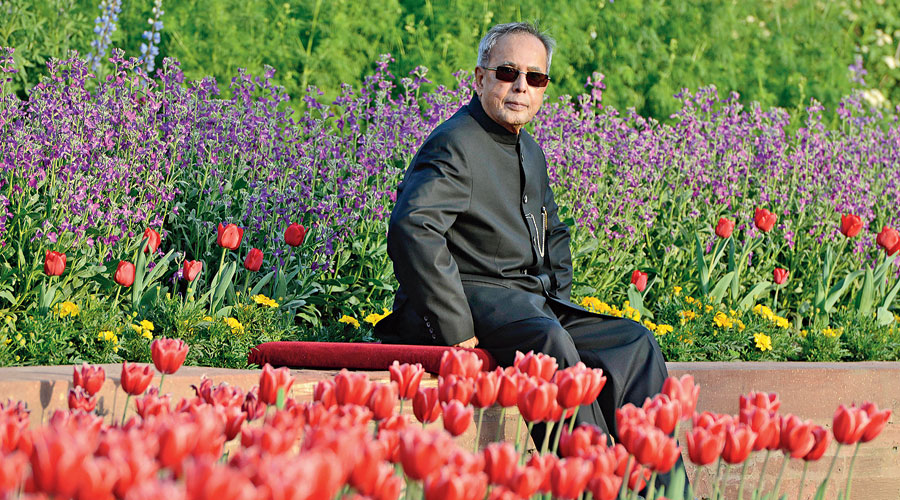

Pranab Mukherjee was a unique character in Indian politics who had to contend with countless little ironies all his life.

A crafty politician who understood the intricacies of mass politics better than anybody else but wasn’t a mass leader.

A loyalist who couldn’t bridge the supreme leader’s trust deficit. A quintessential Congressman who was conferred Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian award, by a government that has vowed to finish the Congress.

A Union minister often alleged to have helped Dhirubhai Ambani build his financial empire but who remained largely spotless throughout his long political stint.

A wise man whose patience and perseverance sustained a rising political career for six decades but who could fly into a blind fury without a reason.

A team man and a consensus-builder who defied the Congress wish and addressed an RSS congregation.

A hardcore traditionalist who yearned for political relevance even after retirement from the top constitutional post.

Ironies don’t end here. Mukherjee’s long political career has no parallel in Indian politics. He wielded more power than the contemporary mass leaders of his time, signifying how political clout isn’t synonymous with electoral appeal in Indian politics. Mukherjee remained in Parliament from 1969 through Rajya Sabha nominations and got elected to the Lok Sabha only in 2004.

He was also an integral part of the Congress high command structure — in its working committee for 23 years — despite the trust deficit generated by his exit from the party in 1986 when he fell out with Rajiv Gandhi.

Although the general belief is that the differences with Rajiv occurred because he expressed his desire to be the interim Prime Minister after Indira Gandhi’s tragic assassination in 1984, it is very unlike Mukherjee to come upfront with his desires as he always chose to manoeuvre his way quietly. Mukherjee wrote in his book The Turbulent Years: 1980-1996 that he along with some other leaders suggested to Rajiv that he take over even though by convention the senior-most minister should have been sworn in.

Mukherjee, however, did object to the haste as some people wanted the swearing-in to be done by Vice-President in the absence of President Zail Singh. This allowed many of his rivals to influence Rajiv against him.

Mukherjee wrote that he enjoyed Rajiv’s trust for months after that incident but was suddenly dropped from the ministry after the election victory. This led to differences and he formed his own Bengal-based party but returned in 1989.

The story about his prime ministerial ambition refused to die and this was used to create suspicions in the mind of Sonia Gandhi about the veteran leader who failed to win her full confidence despite working closely as her key aide. He invariably headed the committees formed for the Congress plenary and acted as chief strategist when the party was struggling in the Opposition between 1998 and 2004.

When Sonia chose Manmohan Singh as the Prime Minister in 2004, ignoring Mukherjee’s seniority and political stature, he was deeply disappointed but demonstrated the maturity to work under his junior without any grudge. Many cabinet ministers felt Mukherjee was Singh’s main strength in the government.

Mukherjee suffered another jolt in 2009 when the UPA returned to power for the second term and Singh was retained as Prime Minister. He saw 2009 as the last opportunity to fulfil his dreams.

Though some Congressmen believed Manmohan would be replaced midway through his second term, Mukherjee knew Sonia’s mind better than others and decided to focus on the President’s post that was to fall vacant in July 2012. He had confided in some of his aides that prime ministerial possibilities were over and occupying Rashtrapati Bhavan could be the consolation prize. He knew it would not be easy but started working on every possible ally to bolster his prospects.

Mukherjee, a hardcore traditionalist, was not only ready to bear the burden and heat of the day for his party — he often gave appointments to people after 11pm after finishing his work — but also commanded respect cutting across party lines.

Famous for his sharp memory, rattling out dates and political events with amazing ease, he nurtured a serious interest in the economy, drafting political documents and external affairs.

Congress veterans respected him for understanding the system better than anybody else, having handled commerce, finance and foreign affairs in various Congress governments for decades. He was also the deputy chairman of Planning Commission and served on the board of World Bank, IMF and other international financial institutions.

Even as President, his political activism manifested in subtler forms as he spoke his mind on every subject of contemporary politics. He gave most insightful and political speeches that some of his predecessors either avoided or were incapable of.

Even after retiring from Rashtrapati Bhavan, he remained active, meeting people from all walks of life almost daily.

He continued to have strong views on the Congress, often expressing his displeasure at the functioning of the party that he felt should regain its strength to protect India’s democracy. Such was his involvement in politics that many Congress leaders speculated that he could be the party’s candidate for Prime Minister in the 2019 general election.

His relationship with Prime Minister Narendra Modi was surprisingly cordial, causing heartburn and suspicion in the Congress. Modi, too, made the most of it, showering effusive praises on him while ruthlessly criticising members of the Gandhi family — from Jawaharlal Nehru to Rahul Gandhi. The Modi government conferred the Bharat Ratna on Mukherjee in 2019, further deepening the distrust that many Congress leaders always nurtured about his intentions.

What gave credence to the views of his critics is his extraordinary decision to accept the invitation extended by RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat to address the pracharaks at its Nagpur headquarters.

While the Congress openly opposed this idea because a former President and a Congress veteran visiting the RSS headquarters would legitimise the divisive ideology that was held responsible for the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, Mukherjee thought the country was already engaging with them as the ruling party. He felt the need for a debate as the RSS was no longer a fringe organisation after the people of India voted for the BJP across the country, making it the biggest party that shaped India’s destiny.

Although he asserted the vitality of constitutional principles and secular values in his speech, the Congress leadership could not forgive him for the gifting the RSS the advantage of a symbolic victory.

Even during Modi’s prime ministership, despite friendly relations with the government, Mukherjee espoused the value of tolerance and social harmony in his speeches. In 2016, he said in a speech that democracy was not about numbers alone and that the rule of law should be the sole basis for dealing with any challenging situation.

He said: “The diversity of our country is a fact. This cannot be turned into fiction due to the whims and caprices of a few individuals. We derive our strength from tolerance. It has been part of our collective consciousness for centuries. It has worked well for us and it is the only way it will work for us.”

This was yet another irony of his life — a leader committed to secularism who faced criticism for legitimising the communal forces by his tactics.

India grieves the passing away of Bharat Ratna Shri Pranab Mukherjee. He has left an indelible mark on the development trajectory of our nation. A scholar par excellence, a towering statesman, he was admired across the political spectrum....

Narendra Modi

...In his death, our country has lost one of its greatest leaders of Independent India. He and I worked very closely in the Government of India and I depended on him a great deal for his wisdom, vast knowledge and experience of public affairs.

Manmohan Singh

Pranabda had been such an integral and prominent part of national life, the Congress party and the central government over five decades, it is hard to imagine how we can do without his wisdom, experience, sage advice and deep understanding of so many subjects....The Congress party deeply mourns his loss and will always honour his memory.

Sonia Gandhi

It is with deep sorrow I write this. Bharat Ratna Pranab Mukherjee has left us. An era has ended. For decades he was a father figure. From my first win as MP, to being my senior Cabinet colleague, to his becoming President while I was CM.... So many memories. A visit to Delhi without Pranabda is unimaginable....

Mamata Banerjee