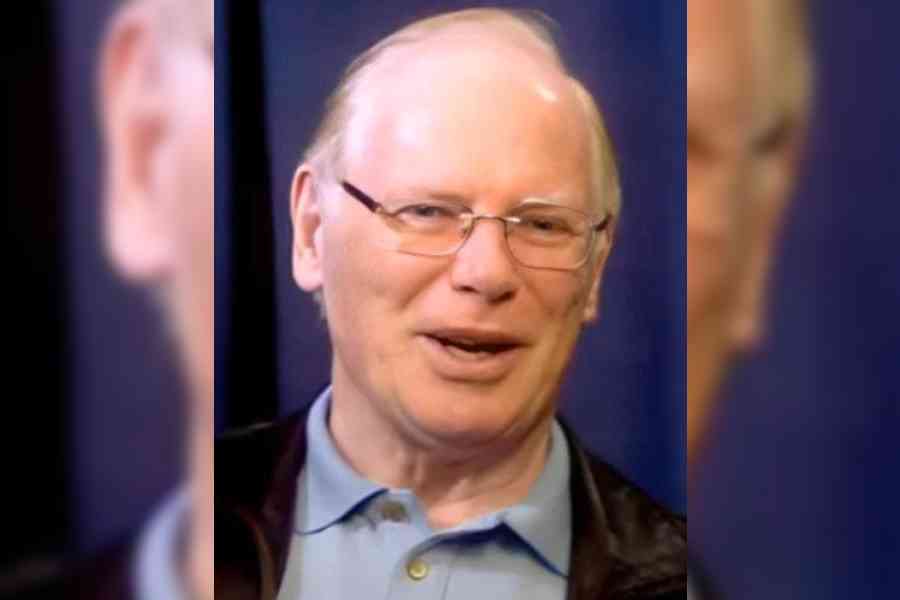

When I enter Feroze Varun Gandhi’s home in Delhi’s Jor Bagh, I can hear Vedic chants emanating from one of the rooms deeper inside the house. I can smell sandalwood and ghee too. Varun informs me that they are having a Navchandi paath. The ritual prayer is for his mother and Union minister Maneka Gandhi, who hasn’t been keeping well lately. She had stopped by earlier in the day.

Varun lives in this house with his wife, Yamini, and their daughter, Anasuya. The drawing room, where we are seated, overlooks a garden; the windows overlooking it are large and it feels like we are outdoors. The walls are chock-a-block with art — S.H. Raza, Ramkinkar Baij, Rabindranath Tagore, Jamini Roy. There is a painting of a young Varun and his mother on one wall; it is by M.F. Husain. There were a few sculptures in the hallway. Following my gaze Varun says, “There lies an ocean of memories with everything I have. The wealth of those memories exceeds any material value.”

In person, Varun is soft-spoken, quite unlike the image he left the public with when he fought the Lok Sabha elections for the first time in 2009, under the BJP banner. The fact that he has not given a television interview in the last eight years hasn’t helped alter that image of him as a bit of rabble-rouser.

We start talking about his latest book, A Rural Manifesto: Realising India’s Future through her Villages, which has been well-received for its research and insights into rural India. He says he had set out to write a book on the history of citizens’ movements in India, but during his tour across the country, he realised the state of the rural economy was a more pressing issue. “Rather than writing a purely academic book, I will write a book which will be useful to people. It was originally 1,600 pages. I had to whittle it down to this size [825 pages]. My publisher said, ‘If you cannot hold the book in your hand, how on earth will you read it’,” he laughs.

I notice how during our conversation, Varun tends to pace up and down whenever he is speaking on something that is close to his heart. He remains seated when he wants to weigh his words. But right through his manner is unhurried, though he doesn’t appreciate being interrupted mid-sentence. “I will lose my train of thought,” he tells me.

The book is packed with distress stories from the Indian hinterland. Varun says, “Rural distress is undeniable, but you cannot blame one government for this. There are deep structural factors that have prevented any state or central government from drastically turning the rural economy around. We need to look at wholesale reform across the entire agricultural value chain.”

He clarifies without my asking: “My approach to everything is academic rather than political. You can see by the way I talk and address issues.” And I jump to that bit in the book where he argues that loan waivers are not a great way of mitigating farmers’ problems.

“That the Indian farmer requires a loan waiver today is a foregone conclusion with the incidence of debt in farm households increasing from 24 per cent in 1992 to 52 per cent in 2016. The average debt among agricultural households is about Rs 1 lakh and above, whereas the income is as low as Rs 9,000 per month. In other words, average debt is roughly the annual income. They are caught in a spiral of ever increasing debt,” he rattles off.

He gets talking about other ways of raising farmer incomes — subsidies in fertilisers and pesticides, rationalising urea usage — and that’s how we get to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act or MGNREGA. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has called it “a living monument to the failure of the Congress party”.

Varun seems to hold a divergent view. He says, “I believe strongly that it had a positive impact on the rural economy by providing meaningful employment to millions of people, creating a wage flow in the rural labour market, increasing women’s participation in the labour force, and controlling regional migration.”

But why then has this government been downgrading MGNREGA by decreasing allocations and diverting funds? Varun offers, “The decrease in MGNREGA funds has happened year on year since 2010. Somebody in these departments started having a thought that this is a scheme that is not paying its way forward. It is not proper to look at it in a way that a business functions.”

This is no one-off, Varun has long had a “subaltern” approach to problems rural India is facing currently and has solutions that may not be wildly popular with the Modi government. For instance, he cites the success of Kerala’s Debt Relief Commission that has resulted in almost zero farmer suicides. He calls it a “transparent and humane approach” that could be replicated across the country.

He talks about other possible solutions such as a basic income scheme for rural households, on the lines of the popular Rythu Bandhu scheme of Telangana. In fact, there are indications that the central government may come up with one in the run-up to the elections. I ask him this and he replies, “I don’t know for sure, but I do know that there is an attempt by the government to look at some form of universal basic income to mitigate the severity of the farmers. I personally have given certain suggestions for Niti Aayog and for some ministries. It is a little above my pay grade to say anything more.”

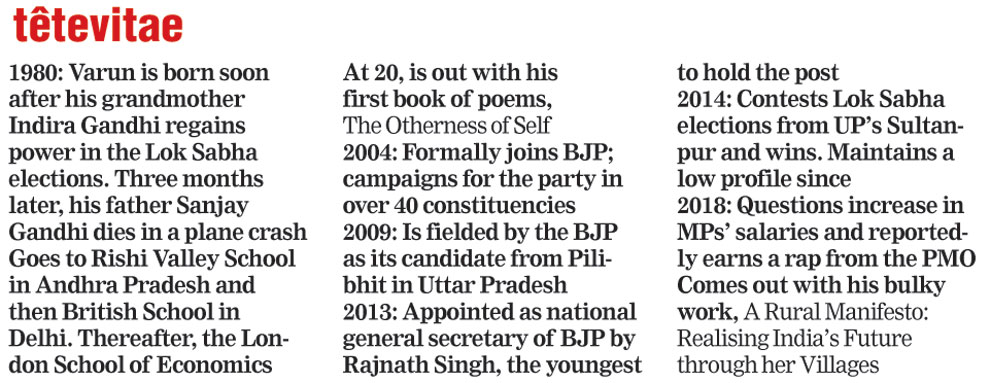

The conversation now shifts to him and his political career, his initial meteoric rise in the BJP and how he was thereafter relegated to the margins ever since Narendra Modi became the PM. In response, Varun recounts how he became the secretary of the party at 29, a general secretary at 31 and was also poll in-charge of Bengal and Assam. He says, “I became general secretary at an age when many people cannot even think of it. But I see it this way — an organisation is always greater than an individual’s aspirations. My primary motive was of service and be part of something that is larger than myself.”

A diplomatic reply, but doesn’t he feel that he is perceived as a threat by leaders within his own party? Is that not why he has been given no responsibility? It is also said that he was expected to take on his cousin, Rahul Gandhi, and he refused. The marginalisation was the consequence. Varun says, “In these years, I have taken up many issues that were academic but not strictly sticking to the party position, never have I been dissuaded. I am grateful for that. My mother, who has been a Cabinet minister in both the NDA governments, and I, have been treated with dignity and I have no complaints.”

There have been rumours from time to time that he will join the Congress, that he and Rahul have discussed the issue several times. He replies without battling an eyelid, “I am not the kind of person to ever think of changing track just because it would suit me. That would never be the case with me. I would always look for much deeper meaning within myself.”

Varun’s Lok Sabha constituency is Sultanpur in Uttar Pradesh, a seat he won rather easily the last two terms. But with the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party coming together, it may not be such a smooth sailing this time. He acknowledges that it is a “formidable combination” but continues to be confident, “I have worked consistently and assiduously for the betterment of the constituency with particular focus on hunger, justice for marginal farmers and setting up of co-operatives. Alliances can be formidable but they don’t always add up to a perfect arithmetical total. No matter what the challenge is, I attempt to meet it with grace and purpose.”

What are his plans for the future? For now, all he can think of are the other two books to complete the trilogy. One will be on India’s crumbling cities and the other on the history of citizens’ movements in the country. There is a collection of poetry that he wants to publish before those two books, but not before the elections. He says with a laugh, “It is called Surrender. If it is published before the elections, people may think I am giving up.”

Touche!

The Telegraph