Kashmir’s poets haven’t been completely silenced by the siege. While sharing the sense of hurt and humiliation felt by Kashmiris after the unilateral abrogation of Article 370 and the subsequent lockdown and communications shutdown imposed in the valley by the government, they’ve spoke out through their poetry filled with rage and lament, but also hope.

Huzaifa Pandit, a 31-year-old Kashmiri poet and research scholar, who published his first poetry collection “Green is the Colour of Memory” (Hawakal Publishers, Calcutta) last year, is no stranger to the military siege, having lived all his life in Kashmir.

On August 5, when he heard that Article 370 had been scrapped, he felt a sense of resignation and disbelief. Confined to his home in Srinagar, he spent the first day of the curfew in resigned silence, staring at the walls. Within days he got used to the imposed silence of the curfew amid the communications shutdown.

“I felt a knot in my chest that expanded to the throat as every direction appeared barricaded,” he says.

For the first few weeks post August 5, Pandit would eagerly huddle around the radio, hoping for some positive news. Disappointed, he would spend the rest of the day reading, or writing poems just to distract his mind.

Huzaifa Pandit Source: Majid Maqbool

“First I thought of writing a diary of events as I experienced them post August 5, but I found myself unable to express anything in prose. Then I turned to poetry and wrote a few poems in response to the lockdown in Kashmir,” says Pandit, who has recently submitted his Ph.D. thesis on “Poetics of resistance: Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Agha Shahid Ali and Mahmoud Darwish” at the University of Kashmir.

Pandit has written two poems reflecting on the siege in Kashmir. The first, “Here is a Present”, plays around the idea of a gift from New Delhi announced for the besieged, dispossessed people in Kashmir – the creation of 50,000 jobs announced by the BJP government for the youth of Jammu and Kashmir soon after the abrogation of Article 370.

‘Here is a present

which plunges into the pit of strange words

to draw out curses for our forefathers.

The paper worms spit out the silver hearts

of maps we smuggled through detained windows.

Perhaps they remember when we stormed out

of the barricaded gates like the west wind

and tore the pavements to pieces.

Here is a present

On which the resigned soldiers sling their rifles

And prepare a hasty dinner

from fires mounted on armored rakshaks.

Perhaps we too will be fed

once the sparrows bite our famished mouths.’

(Excerpted Huzaifa Pandit’s poem ‘Here is a present’)

Security personnel in Srinagar (Shutterstock)

The second poem, “Notes for a Stranger”, is addressed to an Indian citizen who wants to buy land, make a house, and settle down in Kashmir following the revocation of Article 370 and bifurcation of the state into union territories.

‘Stranger, greet us in the middle of sun dried

rain, and doze with us in the mustard

of songs sown by the blind singer.

Meet us midway in the night as long

as sudden death.

We are afraid of your breath…’

Stranger, ask the butterfly

of the snow over the masjid dome

and the hunter’s tent in ripe summer

of apple orchards. Pour our honey

over these empty bruises in the grass.

We are afraid of the siege…’

(Excerpted from the poem ‘Notes for a Stranger’)

“My pen is down”

For Kashmir’s legendary poet, playwright and songwriter Bashir Dada, who writes in Urdu and Kashmiri, the abrogation of Article 370 by the BJP government at the Centre felt like a dragger drawn at the heart of India’s 70-year-old commitment to the people of Kashmir.

“Article 370 was a commitment with the people of Jammu and Kashmir. By removing it, the ruling dispensation has shown that it doesn’t care about ethics and promises, but only about the exercise of brute power,” says Dada.

He said people in Kashmir were feeling the slap; there was a sense of humiliation being felt by all, including writers and poets of Kashmir. After August 5, Dada has not penned down a single verse.

“I’ve stopped writing after August 5. My pen is down. Even the writer’s voice inside me is silent in protest,” he says, adding that writers and poets are also feeling besieged in Kashmir. “We also feel a sense of hurt and humiliation over the treatment meted out to our people.”

Hence, a writer or a poet, supposed to be the voice of the voiceless, has also been rendered silent.

Dada believes the absence of widespread protests by the people since August 5 should not be read as a sign of normalcy in Kashmir. “Kashmiris will not forget this humiliation. People might be silent because they are deeply hurt but there will be a reaction,” he says in a voice tinged with anger and hurt. “People in Kashmir know that hatred for petty political gains is used against them as a weapon to further suppress them.”

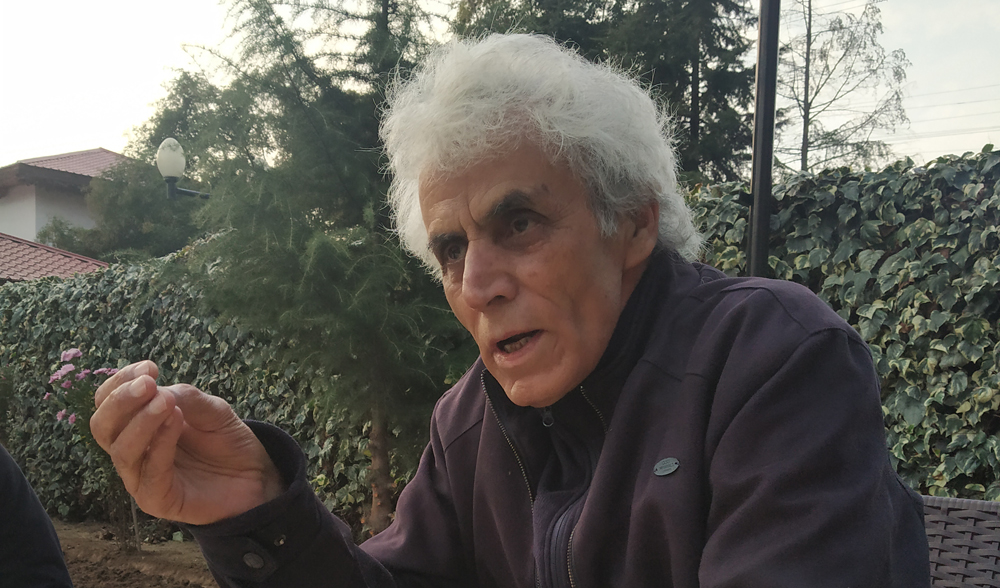

Bashir Dada (Source: Majid Maqbool)

Dada’s poem, “Hazaron Inquilab Aaye”, originally written in Urdu and translated into English as “A Thousand Revolutions”, touches on the theme of oppression and how revolutions that have ended up freeing people from slavery in other nations.

‘A thousand nooses of slavery have been untied free till now.

For some reason I still believed that blind repressive dark rage will come to an end.

I still believed that I could breathe in free air of heavens.

I still believed that my fortunes would take turn and I would be free

I still held this belief.’

(Excerpted from Bashir Dada’s poem ‘A Thousand Revolutions’ originally written in Urdu)

‘What is left to write?’

Another young Kashmiri poet and translator, identifying herself with the nom de plume of Rumuz, said the August 5 lockdown numbed her to the core. She couldn’t – and didn’t want to – write more poems after August 5.

“May be for some people this was a time when the atmosphere was ripe for melancholy or songs or redemption. But for me, I’m still figuring out everything,” says Rumuz, an engineer by profession, who writes poetry mainly in English and Kashmiri.

“Its sinking in slowly, what happened overnight, bringing an entire population of a throbbing culture, values, history, civilization, to their knees by robbing them of their basic identity, their right to socialize, connect, express and live.”

Rumuz’s poems and their translations have been published in various print and online literary journals. She’s also translated into English selected works of Kashmiri poets like Habba Khatoon, Amin Kamil, Mehjoor, Shaad Ramzan and Rehman Rahi.

But now she’s not sure if she’ll ever write again. “You need to be something for that. We have been rendered memory-less,” she says.

Rumuz says the days leading up to August 5 and the subsequent communications shutdown felt like physiological warfare of sorts. “It was like a complete display of brute power and arrogance. Everything boiled down to basics. As if the air we breathed, the food we ate or the homes that sheltered us, were a luxury we had to be thankful to them for,” she says.

“Nobody had any clue as to what was happening. We clung to what was immediate like a terrified child howled at by rabid dogs.”

Identities – that of being a Kashmiri, a poet, or a professional – all evaporated from the surface of conscience, she says, recalling the initial days and weeks of siege. “Basic survival as a human being appeared to be the most important job at hand,” she says.

Recently, when the mobile phone ban had not yet been lifted, she heard an old man saying on television that he was obliged to the authorities for allowing him to speak to his son who’s based outside the state. After waiting in the queue for six hours, the old man was finally able to speak to his son for two minutes on a local telephone booth set up in the DC’s office.

“I’m struggling with shame,” Rumuz says in conclusion, reflecting on the condition of her people. “What is left to write?”

On December 10, after more than four months, Rumuz shared a new poem filled with rage and grief for the first time on her Facebook page where she would often post her work before the internet was shut down on the night of August 4. The last post on her page, dated August 4, spoke of being together in distress, and of hope amid the gloom. “Live my people, live for living is the only resistance here,” she wrote.

“elegies break

into infinite sharp shards

of revengeful silence;

any which way you shall tread,

however far away you elope

into the valleys of forgetfulness

of your victim's frail memory or

blissful graveyards where screaming guilts or throbbing

consciences lay buried,

graveyards you thought were undiscoverable,

any direction you may sunbathe in

to lighten the tan your soul is stained with

go, run, elope, fly...

anywhere;

your share of shards,

awaits you.”