Hiding in his home in Herat with his small children, Haider Abdullah (name changed on request) prays that the gunshots do not resume.

“My children are scared. There was such terrible sound of weapons outside that they did not come out for three days,” the Afghan liver transplant patient in his mid-30s said when The Telegraph called him on Friday. Abdullah is one of the several Afghan patients whose treatment was done in India.

“They are scared of the intruders on motorbikes with long beards and carbines.”

It had been over a week since Herat, Afghanistan’s third-largest city, had fallen to the Taliban. “It happened on Thursday (August 12) evening. They entered on motorbikes. There were clashes everywhere — on the main road, near our house.”

Since then, Abdullah, an employee of “a humanitarian organisation”, has not ventured into the city.

Abdullah has been instrumental in tracing the forced marriage of underage girls or widows in Taliban-controlled areas. “If I go into the city, I might get recognised.”

Abdullah has deleted his Facebook account.

The biggest source of his insecurity is that it’s “no longer possible to know who is police, who is army and who is Taliban; all are with guns, using motorbikes or former military vehicles”.

The anxiety of not knowing who to trust is so deep that Abdullah mentions this three times during the one-hour conversation.

All businessmen and government employees are in hiding or have escaped to Iran or elsewhere. “My friends who worked with the embassies reached Kabul on Wednesday and are awaiting evacuation.”

The economic situation is dire. “Exports and imports have stopped. Prices are rising. The exchange rate for the US dollar has shot up to 83-84 Afghanis. A month ago it was 67-68 Afghanis.”

Abdullah does his shopping in his immediate neighbourhood, on the city’s outskirts. “In the city, there was Taliban everywhere; it was frightening.”

The Taliban’s numbers have reduced since Muharram after the Taliban governor instructed the soldiers to return to their villages. They are present only in the town squares now, Abdullah said.

He deeply resents Pakistan. “When the clashes started between the government and the Taliban, the Pakistan borders were open. Local people got evidence of an inflow of Pakistanis in Afghan clothes,” he said.

“These former commandos of the Pakistani army provided leadership to the Taliban. We saw that in Herat. They often got lost as they didn’t know the local roads. Many of them were killed by the government forces. The government posted some of their faces on social media with proof of their identity, but the world never paid attention.”

Abdullah flared up at the suggestion that the local army had caved in easily. “When the Taliban started entering, the army went back to their base about 10km outside the city, near the airport, and kept asking for instructions,” he said.

“I was in touch with people across the city and men in the national army. With Pakistanis getting in, it was not an internal matter and they wanted to fight. But the government leadership was weak. They did not let them launch an operation.”

Abdullah believes that Herat may not have fallen had the army been allowed to act.

“Our army is very well-equipped. There were 8,000-10,000 of them against 500 Taliban. In each area, only five to 10 motorbikes had entered carrying two Taliban each. But the police were few and did not resist. Herat fell in two hours,” he said, bitterness apparent in his voice.

Abdullah thinks the Taliban and Pakistan exerted influence on the political leadership.

“The politicians are rich people, their families live in foreign countries and they have already fled there. What is it to them? The Taliban families also live in Pakistan. It’s we, the poor, who are stuck in our land and suffer.”

He said a local warlord, Ismail Khan, had tried to resist. “There were uprisings (against the Taliban) in many areas but lacked leadership,” Abdullah said.

“In Herat, Ismail Khan collected his former commandos and tried to build resistance, but he was not supported by the local government. The Taliban too sent him a message saying he would not be detained or harmed but he should not fight.”

Abdullah sees no hope of US action. “All of us feel this was political play with the Afghan people. They had a deal in secret in Doha — the Americans, the Taliban and Pakistan.”

He pointed to the water issue with Pakistan. “All our rivers flow into Pakistan. If we have a strong government, we will stop the water. There is also the border issue. So they do not want peace in our country,” he said.

“Also, we import a lot of Pakistani goods. A strong government will make those things locally and stop import. Where will Imran (Khan, the Pakistani Prime Minister) sell his goods then?”

Neither does he trust the Taliban to work for the country’s good.

“They are under the influence of the Pakistani intelligence service. They transferred to Pakistan all the army tanks given by foreign countries. The army also had modern guns like the M4 and the M16, donated by the US. The Taliban looted the military bases and are just selling the guns. Everybody has a gun now,” Abdullah said.

“The army men are angry that they could not fight. They are hiding and living in uncertainty. They have not been recalled by the Taliban. They don’t have a future. They were trained for 20 years. Now nobody values them.”

Afghanistan Vice-President Amrullah Saleh has laid claim to the presidency in President Ashraf Ghani’s absence, but Abdullah does not want any internal fighting.

“Saleh has gone back to Panjshir to start a resistance. This will lead to internal fighting and harm civilians. We will be back where we were 20 years ago. There will be no development. Instead, the Taliban should give all parties a share in power.”

The schools reopened on Thursday. “The Taliban have said girls can wear decent clothes and attend school,” Abdullah said.

He took his boys to school. “They passed an exam.”

Girls have to wear a hijab, it has been ruled, though the burqa is not mandatory. Nor can women work in humanitarian organisations.

“All such international organisations have asked their female staff to stay home. Donors who were supporting these organisations are not interested in a restart. They are waiting for a government to be formed. But the Taliban are not recognised by the international community,” Abdullah said.

This also means he is jobless now. “Other than my wife and children, I support the niece who donated me her liver. I’m the sole earning member.”

As a liver transplant patient, Abdullah needs protection against Covid-19 when he steps out. He also needs his medicines from India. “These expensive medicines are not sold in Afghanistan.”

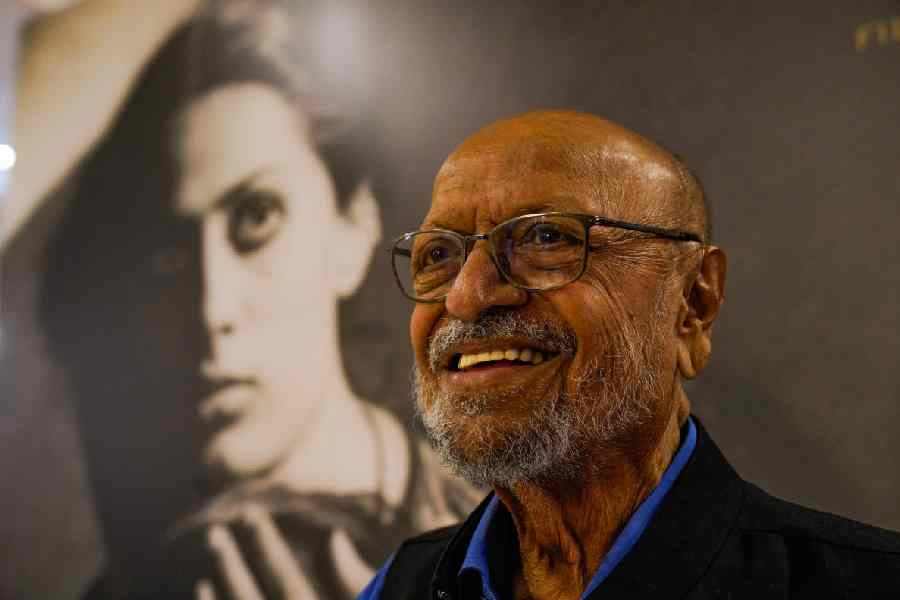

This is why his surgeon Ramdip Ray, who is now based in Calcutta (the operation was done in another Indian city), sent him a text message asking if he had medicines in stock.

“My Afghan patients depend on their India trips for check-ups and medicines. It will be terrible if they cannot travel. Although my male patients responded, I failed to connect with a lady in Mazar-e-Sharif and am worried,” Dr Ray said.

Abdullah wants to visit in December, which is when his medicines will run out. “But I need the Indian embassy to reopen to get my visa. Everything is uncertain,” he said.