A global assessment of pharmaceutical pollution of rivers has detected anti-diabetic, anti-epileptic and pain-relieving drugs, among other medicines, in river water samples worldwide, including from Delhi and Hyderabad, flagging potential hazards to ecology and human health.

The study, the first to comprehensively measure pharmaceutical ingredients in rivers, has found the highest concentrations in lower middle-income countries such as India with large pharmaceutical production capacities but poor environmental regulations.

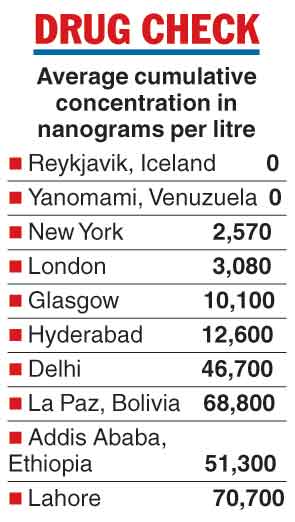

The average concentration of total active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) ranged from zero in samples from Yanomami, a remote village in Venezuela that doesn’t use modern medicines, to 3,080 nanograms per litre in London, 46,700 in Delhi, to 70,700 — the highest — in Lahore.

“We’ve known for almost two decades that pharmaceuticals make their way into the aquatic environment where they may affect the biology of living organisms,” said John Wilkinson, an environmental researcher at the University of York in the UK who led the study.

But almost all studies until now had focused on North America, Europe, and China.

Wilkinson and his colleagues, including scientists at the Indian Institutes of Technology, Delhi and Hyderabad, analysed API concentrations in samples from 1,052 sampling sites from 258 rivers in 104 countries, including sites in the Yamuna river in Delhi and the Krishna and Musi rivers in Hyderabad.

Their exercise detected four APIs — caffeine, nicotine, paracetamol, and cotinine, a byproduct of tobacco, all of which are ingredients of lifestyle or stimulant compounds — in samples from all the continents, including Antarctica.

The India samples contained analgesics, antibiotics, anti-convulsants, anti-depressants, anti-diabetics, anti-allergy medications, and cardiovascular drugs called beta blockers, among other APIs, including the stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine.

India had the world’s second highest concentration of anti-diabetic APIs at 21,000 nanogram per litre, after Bolivia’s 25,400. In comparison, the UK’s anti-diabetic concentration was 1,550 and the US 635. The study’s findings were published on Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The concentration of at least one API at a quarter of the sampled sites worldwide were greater than levels considered safe for aquatic organisms. Although there is no direct evidence yet for human harm from such contamination, scientists are concerned that if API concentrations in the bodies of aquatic organisms consumed by humans for food reach levels close to therapeutic concentrations required by humans, there could be effects on humans.

High levels of antibiotics in the environment could also contribute to drug-resistance in microbes. The concentrations of nine of the 13 detected antibiotics exceeded safe thresholds for at least one sampling site, with ciprofloxacin exceeding the safe limit at 64 sites worldwide.

The greatest deviation from the safe threshold was for an antibiotic called metronidazole in Barisal, Bangladesh, where its concentration was over 300 times higher than the safe limit.

The study found the highest API concentrations in lower-middle income countries than in either high-income countries or the poorest countries.

The researchers said this is probably because lower-middle income countries have limited wastewater treatment infrastructure but their populations have greater access to medicines than populations of low-income countries.

While low-income countries also have poor wastewater treatment facilities, low access and affordability of medicines keeps their API concentrations low.