Saraswati Parida, a housewife in the Odisha village of Garh Nipania, feels “trapped” in the government pension scheme she had signed up for four years ago but wants to quit now.

She says she was not told the scheme, which entails a 32-year gestation period for her, had no exit route.

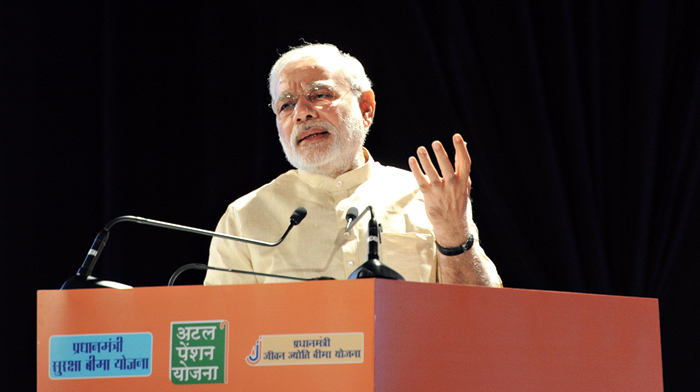

Cajoled by officials of a local public sector bank, she had in December 2015 enrolled herself in the then newly launched Atal Pension Yojana (APY), a contributory pension scheme the Narendra Modi government touted as a major welfare initiative.

“I want to drop out. It’s difficult for me to pay Rs 388 every month. I have requested the bank to return the money I have contributed. They are saying I shall have to forgo my contribution. I’m trapped. Please tell me how I can get my money back,” Parida pleaded with The Telegraph over the phone on Saturday.

The mother of two said her three-year-old daughter’s playschool fees and the cost of transport comes to Rs 600 a month. (Her six-year-old son goes to the nearby government school.) The family’s only income is the Rs 6,000 a month her husband Kabochandra Parida earns as a mason.

In May 2015, Modi had launched the APY as a scheme open to all adults between 18 and 40. The subscribers — and their spouses after their death — are to receive monthly pensions after turning 60.

The pension can be Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000, Rs 3,000, Rs 4,000 or Rs 5,000, depending on the subscriber’s monthly contribution, which varies according to the age at which he or she joins the scheme.

For instance, an 18-year-old has to pay Rs 126 a month for 42 years, with the central government contributing a maximum of Rs 1,000 a year for five years (again, the sum hinges on how much the subscriber is paying).

After the death of the subscriber and their spouse, their nominee gets back the entire corpus, made up of the accumulated contribution over the years and the interest it had earned till the subscriber turned 60.

Saraswati was 28 when she enrolled in the scheme. She will receive a monthly pension of Rs 4,000 after turning 60, which is 28 years away.

“My husband is a mason. We have no other income. It’s difficult to pay the contribution every month,” she said. “Had I been told there was no exit option, I would not have signed up. It’s a trap.”

A subscriber can exit the scheme only if she is afflicted with a terminal disease; and the spouse too can opt out if the subscriber dies before turning 60. In such instances, the contributor’s family receives a refund, including the accumulated interest, after the deduction of maintenance charges.

Data obtained from the Pension Fund Regulatory Development Authority through an RTI application show that over four per cent of the subscribers to the scheme — 6.6 lakh out of the 1.54 crore enrolled — have dropped out.

Still, the government early this year launched another contributory pension scheme — the Pradhan Mantri Maan-dhan — for unorganised-sector workers, farmers and small traders aged 18 to 40. The scheme promises each subscriber a monthly pension of Rs 3,000 on turning 60.

According to the labour and employment ministry website, what the subscribers to the Maan-dhan scheme contribute monthly, the government matches every month.

A subscriber aged 18 has to contribute Rs 55 a month till they turn 60; those signing up at 29 or 40 have to contribute Rs 100 or Rs 200 a month, respectively.

Labour economists and activists said they doubted how successful these schemes would be in delivering pension given the volatility in the job sector and the schemes’ long gestation periods.

Virjesh Upadhyay, general secretary of the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, the RSS labour arm, attributed the APY’s high dropout rate to the uncertainty in the job market. He said the Maan-dhan scheme was likely to witness similar dropout levels.

“Unless the government ensures continuation of a worker’s employment, how can the worker ensure continuity of contribution?” Upadhyay said.

“Only if the subscribers’ savings grow can they continue their contributions. What they earn now is not enough.”

The Maan-dhan has three big differences with the APY. One, the government has promised to keep contributing through the entire period of the scheme, compared with only five years under the APY.

Two, the Maan-dhan allows an exit option. If subscribers want out, they get back their accumulated contributions at varying interest rates depending on whether they are pulling out before or after 10 years.

Three, the Maan-dhan does not return the corpus to any nominee after the death of the subscriber and their spouse.

‘Illusory’

Amitabh Kundu, a labour economist and a distinguished fellow at the Research and Information System for Developing Countries, a policy research institute, said the government’s vaunted contribution of 50 per cent under the Maan-dhan scheme was “illusory”.

Kundu cited calculations he had done on the basis of an 18-year-old worker’s contribution over 42 years. He said the accumulated corpus was good enough to generate a monthly pension of Rs 3,000 assuming an annual interest rate of 8.6 per cent (roughly equal to the interest paid by the Employees’ Provident Fund).

“If a worker receives no contribution from the government and deposits his own share of Rs 55 a month from age 18 to 60, the corpus would be a bit less than Rs 3 lakh under the recurring deposit schemes that banks offer,” he said.

“With this corpus, the worker stands to get Rs 3,000 a month at an interest rate of 8.6 per cent (the pension includes a slice of the corpus, too, calculated on the basis of a life-expectancy formula). So the government’s claim that it is contributing about 50 per cent under the Maan-dhan is illusory.”

Kundu added: “If the government makes a contribution matching the subscriber’s and the pension is still Rs 3,000, it means the government is paying very low interest. But the unorganised-sector workers, who are poor, ought to get even higher returns on their money than their organised-sector counterparts. Under certain special schemes, economically better-off people receive this (around 8.6 per cent) interest on much larger sums.”

Labour economist Ravi Srivastava said the long gestation periods involved in these contributory pension schemes mean that by the time the subscriber receives the pension of, say, Rs 3,000 a month, inflation would have drastically reduced the sum’s purchasing power.

More than 30 lakh people have already enrolled in the Maan-dhan scheme over the past six months.

Social activist Nikhil Dey, whose organisation Pension Parishad has been demanding universal non-contributory pension, said informal-sector workers cannot be expected to pay regular contributions.

“They have no assured income. It’s not possible for them to pay their contributions every month for 30 to 40 years,” he said.

Dey said the government must provide a “respectable” pension to every aged, disabled and widowed person from its own budget.