Mahatma Gandhi spent six crucial days from May 9 to 14 in 1947 in Sodepur near Kolkata, discussing with Sarat Chandra Bose and Abul Hashim a plan to prevent partition and preserve the unity of Bengal. The united Bengal plan was founded on the principle of an equitable sharing of power between Hindus and Muslims that had been first articulated in Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das’s Bengal Pact in 1923 exactly a hundred years ago.

The Muslim League government was to be replaced immediately by a coalition with equal representation of Hindus and Muslims. Joint electorate and universal adult franchise would be the basis for a future Bengal legislature in a marked departure from separate electorates and a highly restricted franchise of the colonial era.

On hearing that Sarat Bose’s meticulously detailed plan had received the Mahatma’s blessings, Syamaprasad Mukherjee went to Sodepur on May 13. “An admission that Bengali Hindus and Bengali Mussalmans were one,” Gandhi told the Hindu Mahasabha leader, “would really be a severe blow against the two-nation theory of the League.” He tried but failed to get Syamaprasad to evaluate the scheme on its merits.

Upon British prime minister Clement Attlee’s announcement on February 20, 1947, that the British would quit India by June 30, 1948, at the latest, the Hindu Mahasabha had been the first to demand the partition of Punjab and Bengal. The Congress Working Committee echoed the Mahasabha’s line by passing a resolution on March 8, 1947, calling for the partition of Punjab.

Congress president Jawaharlal Nehru explained that the principle of partition may have to be applied to Bengal as well. Gandhi, away in Bihar dousing the flames of communal violence, was dismayed that such an unprincipled resolution had been adopted with no reference to him.

“By accepting religion as the sole basis of the distribution of Provinces,” Sarat Bose said to the press, “the Congress has cut itself away from its moorings and has almost undone the work it has been doing for the last sixty years. The resolution in question is a violent departure from the traditions and principles of the Congress.”

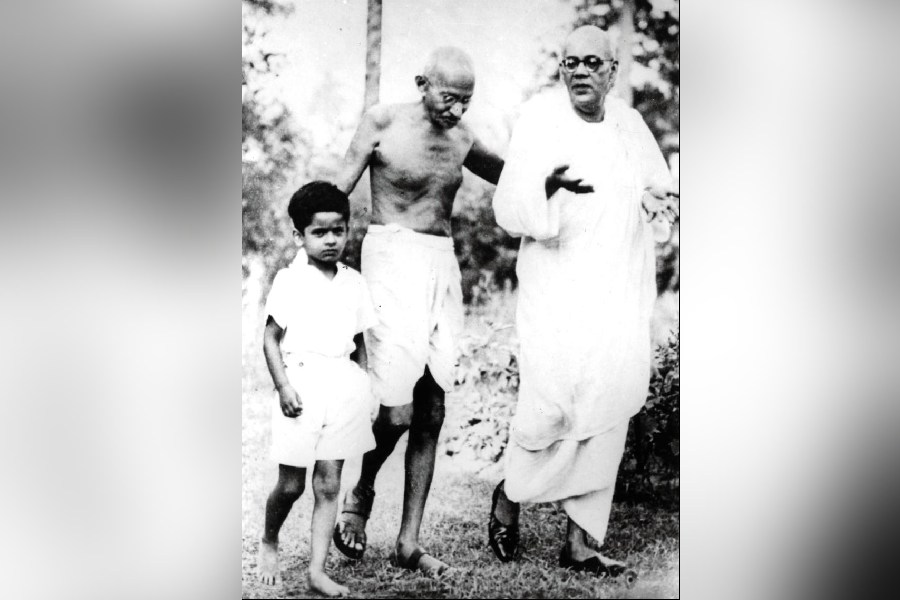

It was in adherence to those principles and traditions of the freedom struggle that the united Bengal plan was forged in opposition to a campaign spearheaded by the Hindu Mahasabha to partition the province. The effort to keep Bengal united received the backing of Jinnah and Gandhi during April and May 1947.

After including amendments suggested by Gandhi, Sarat Bose sent the complete terms of the plan through the British MP George Catlin to Mountbatten. Catlin was a renowned political philosopher, husband of the writer Vera Brittain and father of the future Labor and Liberal Democrat politician Shirley Williams. He was a guest at Sarat Bose’s Woodburn Park home in May 1947. The plan stated that a free and united state of Bengal will decide its relations with the rest of India.

On May 22, Vallabhbhai Patel wrote to Sarat Bose urging him to “take a united stand” with the Congress high command on partition. Sarat Bose replied on May 27, stating that “the united stand should be for a united Bengal and a united India”.

On May 28, 1947, in London, Mountbatten recorded two alternative broadcasts. According to Broadcast B, “Bengal was one of theProvinces for whom partition was demanded, but thenewly formed Coalition Government of Bengal have asked for their case to be reconsidered”.

Mountbatten returned to New Delhi on 30 May and held further talks with Indian leaders until June 2. Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel vetoed the exception for Bengal. That put paid to any possible exception for the North-West Frontier Province as well where a Congress government was still in place. Abdul Ghaffar Khan bitterly complained that the freedom fighters of that province were being “thrown to the wolves”. Mountbatten announced his partition plan on June 3, 1947, that had been the substance of his Broadcast A.

Nehru and Patel were prepared to pay the price of partition to inherit power at the unitary centre of the British raj. The politics that had played out was not just between two religious communities but a tussle between the votaries of a federal union and the champions of an over-centralised post-colonial state.

Sarat Bose denounced the partition plan as “a staggering blow” and felt allowing Bengal and also Punjab and the NWFP to shape their own destiny without imposition from the top “would have eventually led to the establishment of the Indian Union of our dreams”.

At the Congress working committee meeting to ratify the June 3 partition plan, Gandhi complained that he had not been consulted before Nehru and Patel accepted it. Only Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Jai Prakash Narain and Ram Manohar Lohia sided with Gandhi in speaking against partition. Nehru, Patel and Rajendra Prasad ranged themselves against Gandhi.

Sarat Bose had pleaded with Gandhi that if he raised his little finger, partition could still be averted. Gandhi responded that he had been reduced to “a back-number” and that his erstwhile “yes-men” had turned into his “no-men”. Only Gandhi’s “rebellious son”, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, who commanded the trust of all the religious communities and linguistic groups of the subcontinent, could have prevented the human tragedy of partition. But he was no more.

I dealt with what transpired on June 20, 1947, in my 1986 book Agrarian Bengal in a footnote — for that is what it was, a sad footnote in history. Mountbatten had decreed partition on June 3 while adding a hollow statement about ascertaining “the will of the people” through votes in partitioned legislative assemblies of Bengal and Punjab.

On June 20, east Bengal legislators voted by 106 votes to 35 against partition while the legislators of west Bengal voted by 58 votes to 21 in favour of partition. Mountbatten’s plan had provided for partition to go ahead if any one side wanted it. By failing to share power, the machine politicians of 1947 divided the land. It only remained for Cyril Radcliffe to decide where the partitioner’s axe was to fall.

The votaries of Hindutva claim to be devotees of Dasarath’s son Ram, the seventh avatar of Vishnu, according to Puranic tradition. Yet in 1947 and again on the 75th anniversary of partition, they have shown themselves to be worshippers of his predecessor and rival, Jamdagni’s son Parashuram, who had raised his parashu (axe) in a terrible act of matricide.

Nothing can be more bizarre than celebrating at the direction of an overweening central government the vivisection of our motherland that left an estimated two million innocent men, women and children dead and at least 14 million as homeless refugees.