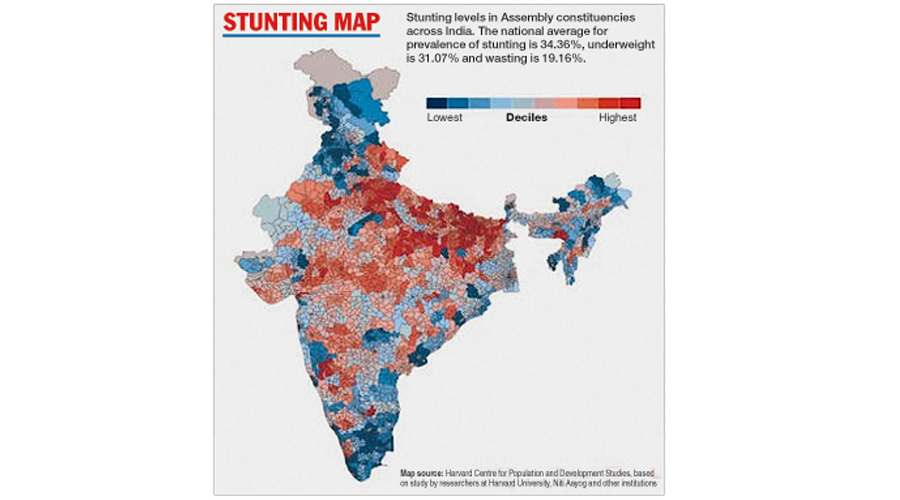

A map generated by health researchers suggests that the zeal to build the Ram temple in Ayodhya has not been matched by efforts to ensure Ram Rajya for the town’s children.

More than half of the children under five in Ayodhya are stunted, a sign of chronic malnutrition, shows the map that estimates for the first time child undernutrition levels across India’s 3,941 Assembly constituencies.

The stunting prevalence in Ayodhya, the launch pad for the Hindutva brand of politics that eventually pitch-forked the BJP to power, is 52.25 per cent and places the constituency close to the bottom of the pile with a national rank of 3,870.

Stunting causes irreversible physical and mental harm. Children who are stunted have low height-for-age, are likely to fall sick more frequently, perform less well in school, and are more likely to suffer from chronic health disorders.

The map — the outcome of a study by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health, the Niti Aayog and other institutions — shows many known pockets of distress but also reveals surprising, unexplained and stark variations within some states.

Kerala, for instance, accounts for 16 of India’s top 20 constituencies with the lowest stunting — Pala (18.02 per cent), Poonjar (18.08 per cent) and Kottayam (18.21 per cent), ranked 1, 2 and 3. But the other four among the top 20 — Sabalgarh, Ambah, Dimani and Morena — are in Madhya Pradesh.

But 26 constituencies in Kerala — Nemmara, Kodangallur, Wadakkanchery, Thrissur and Kochi, among them — have stunting prevalence of 42.8 per cent or higher, their national ranks all below 3,000 and each with stunting levels higher than Bihar’s Jokihat, Lakhisari and Jamui.

Kunnathunad in southeast Kerala has 48 per cent stunting prevalence, a national rank of 3,563, but neighbouring Ettumanoor has 18 per cent and a national rank of 8.

The researchers have published their study’s results in the peer-reviewed journal JAMA Network Open.

“This map should nudge policy-makers into making some meaningful comparisons to learn what’s happening right or wrong within states instead of always comparing Bihar to Kerala,” said S.V. Subramanian, professor of population health and geography at Harvard University who led the study.

“Within states such as Uttar Pradesh, we see Assembly constituencies doing well and, conversely, in Kerala, we see constituencies doing not so well,” he told The Telegraph.

In Uttar Pradesh, for instance, the Thana Bhawan (national rank 90), Kairana (rank 103), Purqazi (rank 117) and Khatauli (rank 119) Assembly constituencies each have stunting levels below 23 per cent, significantly lower than the state average of 44 per cent.

“This study moves undernutrition from administrative units into political constituencies,” said Rakesh Sarwal, additional secretary in Niti Aayog, and one of the study team members. “We would be able to better target, campaign and implement our nutritional programmes.”

Researchers say the findings may challenge current assumptions about which areas of the country merit the biggest concentration of efforts and resources to combat child undernutrition.

On expected lines, the map has found on average lower undernutrition prevalence in the south than in the north. More than 80 Assembly constituencies in Bihar and over 60 in Uttar Pradesh have stunting levels above 50 per cent, including in Ayodhya where stunting is 52.25 per cent.

No Assembly constituency in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana has a stunting level above 50 per cent.

In Bengal, stunting prevalence ranges from 28 per cent in Darjeeling (national rank 783) to 30 per cent in Tollygunje (rank 1,191) to over 40 per cent in Basirhat Dakshin (rank 2,665), Deganga and Haroa, both ranked 2,667.

The study combined child undernutrition data from 640 districts in the 2016 national family health survey with the geographical boundaries of India’s 3,941 Assembly constituencies to measure the prevalence of four key indicators — stunting, underweight, wasting and anaemia.

“This work brings the power of data science to reveal for the first time the nutritional status of children in each Assembly constituency in India, thereby placing a concrete measure of the task at hand in the public domain,” said Rajiv Kumar, Niti Aayog’s vice-chairman, in a media release issued by Harvard.

The study has also shown that not all states rank evenly on all the four indicators. Assembly constituencies in Punjab, for instance, exhibit a relatively low prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting, but a higher prevalence of anaemia.