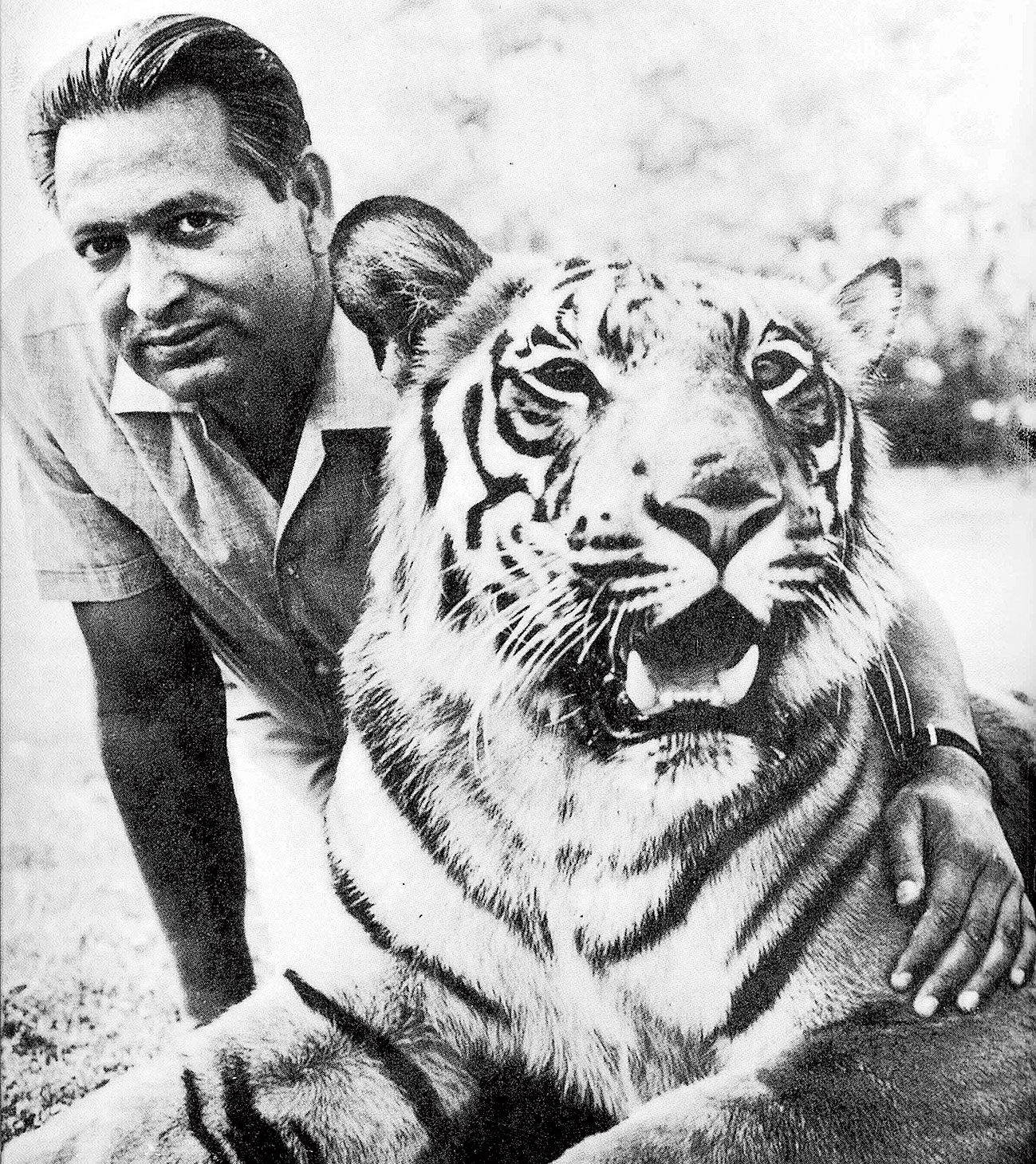

The story of the striped wild cat has been told through a feature documentary — Tigerland — produced by Oscar-winners Ross Kauffman (Born into Brothels) and Fisher Stevens (The Cove) that premiered earlier this year at Sundance Film Festival. It spotlights the efforts of Kailash Sankhala, the conservationist who was the first director of Project Tiger and is famously known as the ‘Tiger-Man of India’. The Telegraph chats with his grandson Amit.

Amit Sankhala, grandson of Kailash Sankhala Sourced by the author

You belong to a forest-oriented family. What were your growing-up years like?

I remember seeing tigers at the age of four or five. But I must have seen them before. My grandfather was with the forest department and ended up being the co-director of Project Tiger. We spent a lot of time in the jungle, sometimes for months at a time. My father would go to Kanha and Bandhavgarh. He ran a couple of lodges in those areas and a non-profit called Tiger Trust which did a lot of work with communities in central India and Rajasthan. In those days in the ’80s, it used to take almost 24 hours to reach a forest. My grandfather died when I was 12 and my father Pradeep died when I was 20. I spent more time in the wild since they passed away.

You must have heard from your grandfather how it was when trophy hunting was in vogue?

Hunting was a big thing in the British Raj and for another 25 years after the British left. It got banned in the 1970s when Project Tiger was launched. That was one of the main aims of the project. Tigers were down to barely 5,000 in the wild the world over. In India, someone needed to count how many were left. That was one of the jobs my grandfather did as part of the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship he got. People saw tigers in the wild and that was it. The fellowship was a government grant to study, which my grandfather used to study tigers in the late ’60s. It was like an informal census with limited resources. His study was commended by the forest minister, Karan Singh, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. That played an important part in moving towards tiger conservation. Some amazing people also made important contributions, like M.K. Ranjitsinh Jhala, a royal from Wankaner in Gujarat, who convinced the maharajas to give up the forests in their estates instead of hunting.

What were the focus areas when Project Tiger was launched?

Project Tiger was launched with nine tiger reserves, including Kanha, Corbett and Ranthambore.

The film focuses on your grandfather’s role in tiger conservation seen through your eyes. What has your role been?

I am in the eco-tourism sphere. I own a wildlife travel company and see how tourism can help the community. A typical problem is wild animals taking away livestock as villagers then get angry and kill the predator. The idea is to reduce man-animal conflict. Tourism is a tool that can be used to provide employment other than farming. That way we can protect the community as well as the tiger and its habitat. We also run Tiger Trust which holds legal training workshops for guards hired in villages surrounding the national parks. They don’t even know what the law is, how to arrest poachers. We bring down lawyers from Delhi and train them with help from the forest department.

A shot from the documentary Tigerland Still from the documentary

When was Tigerland shot?

In February-March 2018. There is not a lot of footage from India as my grandfather did not leave much. We have about 5,000 slides and letters, the story was told using all that, through my and my nephew’s eyes, using animation.

Did you get to learn anything new by rummaging through your grandfather’s things?

Yes, we realised how well-travelled he was, attending conferences and spending time in Africa to understand how rangers operated there. He never spoke about all that. Or how he would sit by a watering hole for 24 hours at a stretch without food as food would attract ants. He wanted to study what came to a watering hole in those 24 hours — birds, deer or tiger — and would make notes. There were no cameras in those days that they could just leave out.

What about the Russia part of the film? We don’t know much about Siberian tigers.

The Russia part is different. It is on Pavel Fomenko who works for World Wildlife Fund (as director of rare species conservation). He is a very hands-on person. Same passion (as Kailash), but different job. The Siberian tiger is a sub-species of the tiger. They are the only ones other than the Bengal tiger and the Sumatran tiger that are still extant. Indochina, Bali, Javan tiger — they are all gone.

Siberian tigers have adapted to the climatic conditions. You would think they look bigger but their hair is actually bushier.

Recently a photograph went viral of a tiger taking shelter on a bed near Kaziranga. Almost all of Kaziranga National Park is affected by floods.

Flood in Kaziranga has become an annual affair. There is so much construction that it restricts the movement of wildlife. The tiger got scared and crossed the highway. The good thing is the people allowed the tiger to rest for 10-12 hours. It was not like ‘Iss ko abhi bhagao’. The owner of the house even said that he would preserve the bedsheet forever as it has been blessed by the tiger. Eventually, the forest department burnt some fire crackers to make it move back to the forest, which was fine.

Is the attitude to tigers similar in Russia?

The problem is the same. There they have guns so they shoot. In Mumbai, we have leopards getting into people’s homes. But we have got into their homes. Where will they go?

Any reading or viewing material you would recommend for youngsters?

There’s a brilliant magazine called Sanctuary Asia to which if you subscribe you get to become part of Sanctuary cubs and you get aligned to the wildlife network in the country. The editor Bittu Sahgal is also part of Tigerland. Go on nature trips in your vacations. See the works of filmmakers like Mike Pandey and the Bedi Brothers (Ajay and Vijay) who are doing amazing work in India.

(Tigerland will air today on Discovery, Discovery HD World and Animal Planet at 8pm)