An ongoing exhibition at an acupuncture centre in Mourigram, about 13km from Calcutta, is a reminder of a chapter of camaraderie between India and China that had begun just before World War II and continues till today, outside conflict zones.

The exhibition, a permanent installation featuring photographs of the Indian Medical Mission to China in 1938 during the Second Sino-Japanese War, has been put up at the Indian Research Institute for Integrated Medicine at Mourigram. The institute is a reputed centre of acupuncture and owes its origin to the 1938 medical mission of Indian doctors who fought at the battlefront in China.

The photographs tell the story of the mission and the birth of the institute. The exhibition, Bikalpa Brata (Alternative Mission), has been curated by Arindam Saha Sardar of Jibansmriti Digital Archive.

In 1938, after the Japanese had invaded China, Communist General Zhu De had asked Jawaharlal Nehru to send a team of doctors to help the soldiers. It was a cry from a people struggling for their freedom to another.

Subhas Chandra Bose, who was the president of the Indian National Congress then, responded to the appeal. At his initiative, a team of five doctors, who were selected from several parts of India, was organised. “The doctors were Madanlal Atal, team leader, M. Cholkar, Bejoy Kumar Basu, Dwarkanath Kotnis and Debesh Mukherjee,” says Debasis Bakshi, who, with his wife Chandana Mitra, runs the Mourigram centre. “They were all trained in modern medicine,” says Bakshi. He and Mitra, too, are allopaths by their initial training, and are among the leading acupuncturists of India.

The medical mission to China was historical. The Indian doctors were received warmly at Yan’an by Mao Zedong, the future leader of China. From there, the doctors would go to several parts of China that were under attack from Japan. Subhas Chandra had, in a 1937 article, after stating his admiration for Japan, criticised it as an imperial force and for “dismembering” China.

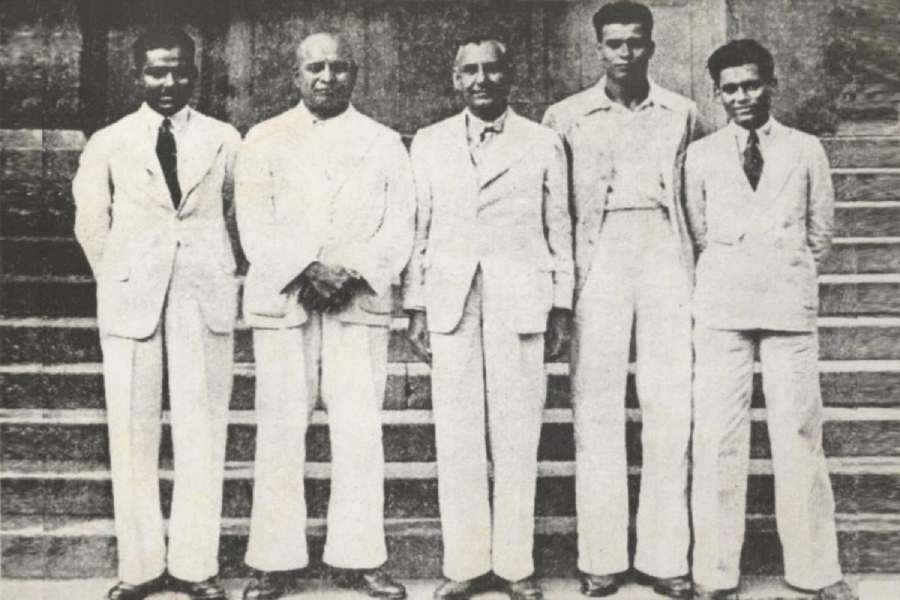

Mission doctors with Mao Zhe Dong.

The doctors, says Bakshi, often did not receive cooperation from the government of Chiang Kai-shek, who would be ousted by the Communists in 1949.

Kotnis’s role in the mission is well-documented. He worked tirelessly in the battlefronts, fighting a severe shortage of medicines. “In spite of acute sickness, Kotnis operated on soldiers for 48 hours tirelessly. He died in 1942,” a write-up at the exhibition says.

Mao and the Communist Party did not forget him. They honoured him as a hero. Back home, V. Shantaram made the film Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani in 1946 on him.

Less known is the story of Bejoy Kumar Basu, who had graduated from Calcutta Medical College in 1936. Bakshi and Mitra, too, obtained their degrees from Calcutta Medical College, where they were taught by Basu.

“His selection for China was dramatic. At first, Ranen Sen had been selected,” says Bakshi. But the colonial government did not want him to go because he was a Communist — sending an Indian party member to China itself was too hazardous. So at one day’s notice, Basu was selected for China. “The British authorities did not know that Basu was also a Communist Party member, a secret one,” laughs Bakshi.

In China, Basu treated wounded soldiers, common people and trained the next line of medical workers. “Amidst bombing,” reminds Bakshi. In 1943, Basu returned to India and engaged himself in freedom movement and humanitarian work. He would introduce a few of his students, including Bakshi and Mitra, to acupuncture, which he had been exposed to in China. Acupuncture, as he wanted to practise and teach, was humanitarian work.

“As a tradition, it is 5,000 years old or older,” says Mitra. It does not require anything else other than a fine needle. The way she and Bakshi practise it, it is also extremely affordable, so also accessible as a treatment for the poor.

“It is perhaps the second most popular treatment in the world, after allopathy,” says Bakshi.

He and Mitra are proof of their belief that there is no contradiction between the two. It is a science, says Bakshi, that works through the application of pressure on or stimulation of certain points of the body and very effective for treating acute and chronic diseases.

“It works by balancing the structure and the functions of the body,” says Mitra. “It goes back to 5,000 years or earlier,” she says, adding that similar traditions can be seen in other Asian civilisations.

Basu did not only introduce a treatment but he was also part of an India-China friendship, an exchange of ideas, that has survived an Indo-China war, the Emergency and relentlessly strained relations between the two countries.

In 1957, a grateful China had invited the members of the mission to the country. In 1958, Basu went to China again to learn acupuncture. From 1959, he introduced acupuncture treatment in India. He practised in Calcutta and started training doctors.

Bakshi and Mitra were among his first students. In 1974, Dr Dwarkanath Kotnis Memorial Committee was revived. This helped to establish several acupuncture clinics in the country.

In 1981, the Research Institute for Integrated Medicine, or IRIIM, as it is referred to, was set up by Basu’s students with Bakshi and Mitra taking leading roles.

In these four decades, the institute has grown. It has also integrated yoga into its practice, which upholds the true essence of India-China friendship, it says. Many people from near and far come to it. It is a non-profit organisation that, inspired by Kotnis and Basu, is trying to reach affordable treatment to common people, remind Bakshi and Mitra, who remain dedicated to it.

The exhibition has 62 photos in three rooms. “We needed to tell the story,” says Bakshi.