This is the centenary of the second-largest inflation recorded in human history — the German hyperinflation of 1923. The exchange rate between the dollar and the mark was one trillion marks to one dollar, and a wheelbarrow full of money would not even buy a newspaper.

Cut to 2023 in India. If we look at inflation numbers, the above example may look dramatic and rightly so. The German story, however, has relevance because it reminds us of the crude reality of price rise, which affects the poorest of the poor even if its softening — by a few points — brings smiles to the faces of policymakers.

After presenting the Economic Survey 2022-23, chief economic adviser V. Anantha Nageswaran said on Tuesday that inflation may not be as big a problem in the next financial year as it was in 2022, even though uncertainties remain.

He is right as a number of factors — like a sharp fall in vegetable prices — resulted in India’s headline retail inflation rate coming down to a one-year low of 5.72 per cent in December 2022 from 5.88 per cent in the previous month.

While Nageswaran maintained that there remains an “upside risk” on the movement of prices, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman seems to have forgotten this possibility while presenting the first budget of “Amrit Kaal”.

Drawn from Vedic astrology — indicating a sort of golden era — Amrit Kaal is extensively used by BJP leaders to claim that the coming period is going to be most prosperous, with economic growth and social justice, for India.

The saffron ecosystem lapped up Sitharaman’s claim that the world has recognised the Indian economy as a bright star, and it is headed towards a bright future, and used social media to create a narrative that will suit the BJP in the upcoming Assembly polls and in next year’s general election.

Claim vs reality

High inflation, job losses and lower income across all sectors had been the biggest realities of the Indian economy in the past three years as common people battled the impact of a pandemic, followed by a war. This period was marked by a sharp rise in inequality in India.

Sitharaman didn’t mention the hardships, as she chose to focus on the brighter side. In her speech, she highlighted that India is poised to grow at 7 per cent in 2022-23, the fastest among all major economies of the world, and took pride in the country’s emergence as the fifth-largest economy despite the global slowdown, high commodity price and the Russia-Ukraine war.

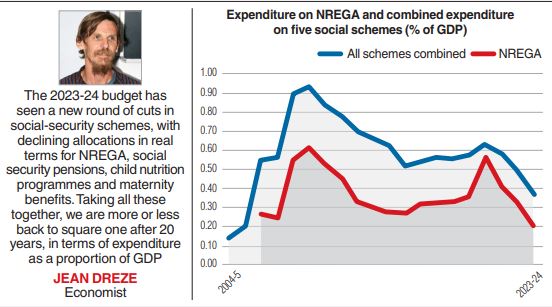

While the claim about the growth story — though incomplete at this juncture — is acceptable to some extent, a closer look at the “Expenditure of Major Items” in “Budget at A Glance” reveals that the commitment to ensure “social justice” is only lip service.

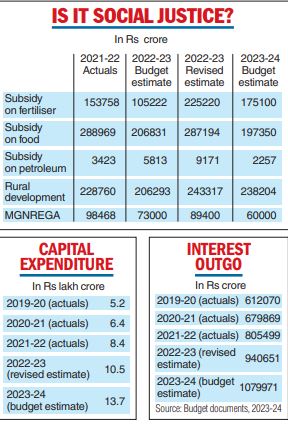

The Narendra Modi government — according to the budget documents — has proposed to spend about Rs 1,50,000 crore less on food, fertiliser and petroleum subsidies in the next fiscal as compared to its outgo in the current year, which will end on March 31. The proposed spending on rural development for the next fiscal is also around Rs 5,000 crore less than this year.

Sitharaman’s budget proposals brought loud cheers in the bourses initially. However, the budget does not have much for the rural poor, whose livelihood depends on projects carried out under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme, as the Centre reduced allocation under this scheme.

The proposed allocations for three different umbrella programmes for the minorities, the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes — a marginal increase for SCs and STs and a sharp cut for minorities — suggest that “sabka saath, sabka vikas” is little else than a claim.

Several holes can be drilled into the narrative of social justice — broadly defined as a concept in which everyone deserves equal economic, poli tical and social rights and opportunities — in Amrit Kaal, if the expenditure budget is looked at closely.

The supporters of Sitharaman may argue that the new direct tax structure proposed in the budget will put more money in the hands of the middle class and help them spend more, which will furtherfuel growth, but this contention doesn’t capture the fullstory.

The finance minister herself said that the total tax foregone on a better tax deal would be about Rs 35,000 crore, which works out to be less than 5 percent of the estimated income tax collection of over Rs 9 lakh crore in the next fiscal. The impact of the largesses, even if positive, will be too little on the economy.

There is little doubt that the deprived sections — a major part of the population that keep facing the brunt of inflation — were expecting some relief, but Sitharaman clearly had other priorities.

Headline grab

The finance minister announced in her budget address that the government would boost the capital investment outlay by 33 per cent to Rs 10lakh crore, which would be around 3.3 per cent of the GDP.

Stressing that increasing capital expenditure was consistent with the government’s goal of providing young people with numerous job options, she added that the outlay was about three times the allocation in 2019-20.

Making it clear that the big story of the budget was the direct capital investment by the Centre, which would be complemented by the provision made for the creation of capital assets through grants-in aid to the states, she said that the effective capital expenditure would be Rs 13.7 lakh crore, around 4.5 per cent of the GDP.

As expected, the markets took the cue and sent energy and infrastructure stocks soaring, indicating that the government had managed to grab the headlines with the announcement on capital expenditure.

The government narrative didn’t end with the capex story on the expenditure side. Euphoria over higher revenue mobilisation — both on the direct and the indirect tax fronts— and the claims on economic recovery complemented it as saffron spin doctors went to town over the arrival of Amrit Kaal.

In her speech, Sitharaman fixed the fiscal deficit target for 2023-24 at 5.9 per cent of the GDP, which would represent a reduction of 50 basis points from this year’s fiscal deficit target of 6.4 per cent. Sitharaman got projected as a skilled trapeze artist who can balance higher spending with fiscal prudence.

The devil, however, lies in the details as some key statistics — like market borrowing and the total interest outgo of the government — revealed that the celebrations over the capex rise could be premature.

The crux of the story: while the government is trying to claim that the rise in capex is fuelled by tax buoyancy, one cannot eschew the fact that its indebtedness is also on the rise, evident from the steep hike in interest outgo in the next fiscal by around Rs 1.35 lakh crore.

Such a high interest burden on the economy, even a layperson can understand, is not a sign of prudent fiscal management in Amrit Kaal.