Treating private and public universities equally, relaxing rules to encourage top foreign institutions to set up campuses in India, and shoehorning Indian traditional knowledge into syllabuses are some of the stated objectives of the new National Education Policy.

The intent, some critics suggested, seemed to be to burnish India’s global image rather than actually improving the quality of education for all.

The policy, announced by the government on Wednesday, does mention a goal of portraying India as a global study destination or “Viswa Guru” — an oft-used term with the BJP leadership.

Government officials and academics agreed that these three objectives made this national education policy distinct from previous ones. The previous policies — the last came in 1986 but was modified in 1992 — were oriented more towards addressing the deficits on the ground.

University Grants Commission vice-chairman Bhushan Patwardhan said the new policy’s stress on “merit-based equal treatment of private and public institutions, and mainstreaming of Indian traditional and cultural knowledge” would turn the country into an education hub.

He, however, also argued that its promotion of schooling in the mother tongue would help remedy systemic maladies.

A human resource development ministry official said the new policy aimed to raise the Gross Enrolment Ratio — the percentage of people aged 18 to 23 who have enrolled in higher education — from the current 26 per cent to 50 per cent by 2035. Britain, Germany and the US have enrolment ratios above 50 per cent, he said.

“This document intends to enhance enrolment in schools, retain students and enable most of them to migrate to higher education. With a GER of 50 per cent, India will be a major global generator of knowledge,” the official said.

Going ‘global’

“India should be promoted as a global study destination providing premium education at affordable costs and restore its role as a Viswa Guru,” the HRD ministry official said.

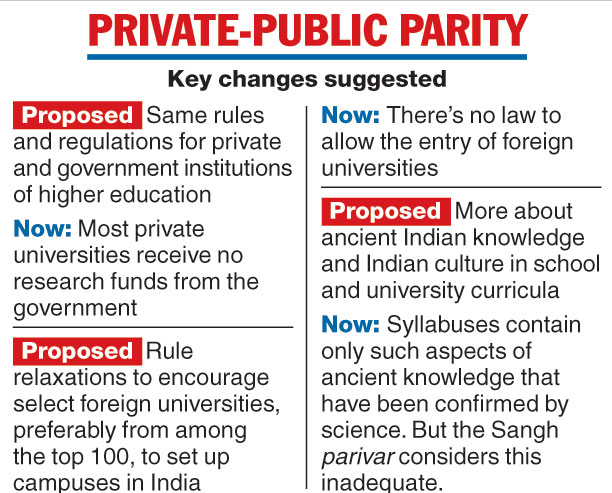

Select foreign universities, preferably those from among the top 100, will be allowed to operate in India, he said. Before that, a law will be enacted to let these institutions function with a degree of independence “on a par with Indian autonomous institutions”.

The UPA government had brought in a bill in 2010 to allow the entry of foreign educational institutions but opposition from most political parties thwarted the proposal.

Fee freedom

According to the policy, the rules and regulations will more or less be the same for private and government institutions of higher education. Currently they are different.

“Private universities are not entitled to UGC research grants now. They may not get infrastructure grants (even under the new policy) but it should become possible to make research and faculty development (training) grants available to them,” Patwardhan said.

Gradually, he said, the private institutions would be able to decide their course fees within a set of broad parameters. But they will have to ensure that at least 20 per cent of their students are taught free and another 30 per cent get scholarships, Patwardhan said.

Currently, every state has government-appointed committees that decide the upper limits for the fees that private institutions teaching professional or technical courses in that state can charge.

Sajjad Ahmed, a teacher in the department of educational studies at the Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi, said that past education policies had focused more on government institutions since the number of private institutions was small then.

“This policy aims to promote the private institutions,” he said.

Tradition, culture

The new policy seeks to include in the school and university curricula aspects of ancient Indian knowledge, especially relating to the indigenous medicine systems, yoga, natural resources and natural farming.

There will also be content on Indian culture encompassing the arts, literature, music, films, customs, linguistic expressions, heritage sites and festivals.

Ahmed said that scriptural content that is yet to be established scientifically should not be included.

“It’s a good thing to learn about Indian heritage and traditional knowledge systems. Earlier policies too included these topics but the scientific temper was the yardstick. So, those proven with evidence were part of the content. That is a sounder principle,” Ahmed said.

Sociologist Andre Beteille said the scientific community would not allow any content that was unproven.

“You have to take the scientists into account. They will not allow anything that is not established yet, like ‘Vedic science’,” Beteille said.

Patwardhan argued that the infusion of traditional knowledge would strengthen any branch of study.

“In line with an integrative approach, the students of allopathic medicine can study ayurveda, unani, siddha, sowa rigpa and naturopathy — and vice versa. There is no problem with learning about Galileo or Isaac Newton, but there is a need to know about Panini and Patanjali too,” he said.

Beteille said the policy seemed full of aspirational ideas but “most of these things will depend on implementation”.

Ruchi Garg, a schoolteacher, welcomed the policy saying teaching in the mother tongue would help the children understand concepts better.