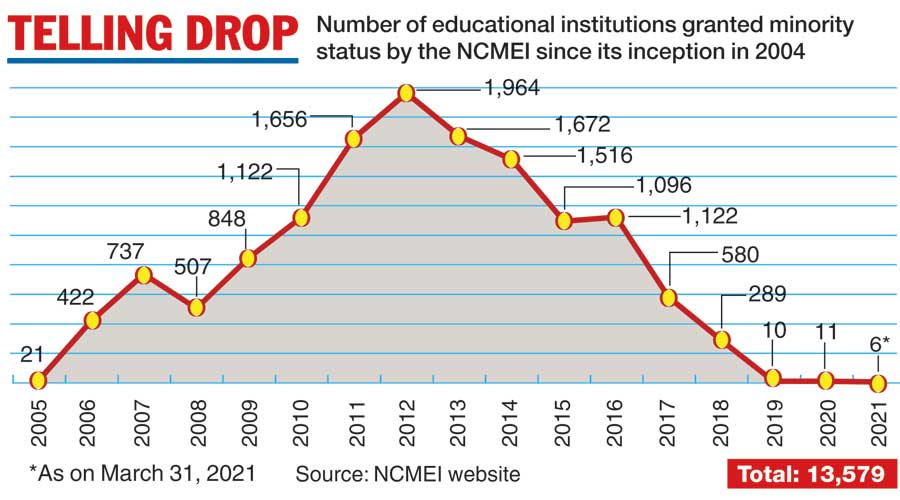

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tenure has seen a sharp decline in the number of educational institutions awarded the minority status by the National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions, a quasi-judicial body funded by the central government.

The commission, established in 2004, can grant the minority status to institutions set up by individuals or organisations from the Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain and Parsi communities.

The state governments too can independently grant the minority status, which allows an institution to reserve up to half its seats for members of its community.

While the Modi government’s early years witnessed a relatively mild decline in the award of the minority certificates by the commission — from 1,500-1,600 a year to around 1,100 — the figures nosedived from 2017, falling to 10 in 2019 and 11 in 2020. (See chart)

An education ministry official blamed the decline on procedural changes in clearing the applications, but academics complained that these changes amounted to “harassment” of the minority institutions and alleged that the motive was “political”.

The four-member commission has three members now: Justice Narendra K. Jain (chairperson), Jaspal Singh and Shahid Akhtar. Jain became chairperson in October 2018.

According to commission records, of the 522 institutions awarded the minority status between August 2017 and March 2021, some 245 had been established by Christians, 185 by Muslims, 70 by Jains, 21 by Sikhs and 1 by Buddhists.

The commission has not published community-wise break-ups of the minority certificates issued before August 2017.

The education ministry official said the number of applications had fallen over the years — from up to 2,000 a year witnessed mid-decade to about 600 a year now.

Asked why the number of certificates awarded had plunged to around 10 a year, he blamed it on delays caused by procedural changes.

An institution can apply to its state government or the commission for the minority status. Following a Supreme Court judgment in 2018 in Sisters of St Joseph of Cluny vs West Bengal, institutions applying to the commission have to attach a no-objection certificate (NOC) from the state government.

The states are often slow to grant NOCs. However, if an institution can furnish proof that it had applied to the state government for an NOC more than 90 days ago, the commission can consider this “deemed NOC”.

“Now the applicants have to furnish an NOC from the state government, and a unique ID from the Niti Aayog if the applicant is a registered society or a trust,” the ministry official said.

An official from an applicant institution, asking not to be identified, provided a fuller explanation of how systematic delays had led to a piling backlog, with just a handful of certificates issued each year.

He said the format for the application to the commission was changed three times between 2017 and 2019, each time seeking additional details such as student and teacher data or imposing new requirements such as the Niti Aayog ID.

“Each time they changed the format, they asked us to withdraw the application and resubmit it. They could have easily asked for an affidavit with the additional information sought,” he said. “The withdrawals and resubmissions led to delays.”

The pandemic has further slowed the process. The commission usually conducts three hearings before awarding the certificate — a process that earlier took between one and two years.

Akhtarul Wasey, academic and former commissioner for linguistic minorities, expressed concern at the repeated changes to the format.

“The commission has no reason to change the format repeatedly. This is harassment of the applicants,” Wasey said.

He demanded that the commission provide year-wise data on its website about the number of applications received.

Jessy Kurian, Supreme Court lawyer and former commission member, said delaying the minority certificates amounted to discouraging the minority institutions.

“Delays defeat justice. The commission should speed up hearings for faster decisions,” Kurian said.

Sociologist Andre Beteille had in March last year told this newspaper he had a feeling that the reasons for the decline in minority certificates were “political”.

“On the whole I’m opposed to quotas of any kind. But something (that had been) going on for decades declining sharply calls for anxiety,” he had said.

“There must be a very sound reason for such decline. I have the impression that the present Prime Minister is not favourably disposed towards minorities. I think it is political.”

An email sent to the commission on August 31 seeking the reasons for the fall in the number of institutions receiving the minority status has evoked no response so far.

However, Justice Jain, the commission head, had told this newspaper in March last year that there was no pressure from the government on the issuance of the minority certificates. He had attributed the falling numbers to delays caused by the format changes.

Former National Commission for Minorities chairperson Naseem Ahmad said the vacancies in the commission too were a reason for the delays. Two members’ posts were vacant till last month, when Akhtar was appointed.