A plan by the Narendra Modi government to bolster India’s research competence through a new agency for which the Union finance minister had last year pledged Rs 50,000 crore over five years remains unapproved and unfunded.

The proposal to create a National Research Foundation (NRF) to support research projects in universities, colleges and other institutions is yet to be approved by the Union cabinet, an official familiar with the proposal’s status said.

It is expected to be approved soon, the official said, explaining that funds would then follow.

Sections of scientists say the lack of progress on the NRF is in line with what some describe as the Modi government’s penchant to make big announcements with disproportionate follow-up.

But others say it is unclear how the NRF will achieve what existing research funding agencies have not.

“The status of the NRF illustrates the government’s strategy — drumbeat announcements, paint a nice picture for the public, then things fizzle out,” said a physicist in a central educational institution who requested anonymity. “The NRF is a great concept, but where is it?”

But some scientists are also worried whether the NRF will concentrate a disproportionate share of available research funds with a single agency, which, some believe, could centralise funding decisions and erode opportunities for collective decision-making.

The concept of the NRF to cultivate research in higher education institutions emerged from the National Education Policy of 2019 to address long-standing concerns that less than 1 per cent of India’s 40,000 HEIs are engaged in any research.

Across science circles, there is consensus that India can do far better in research.

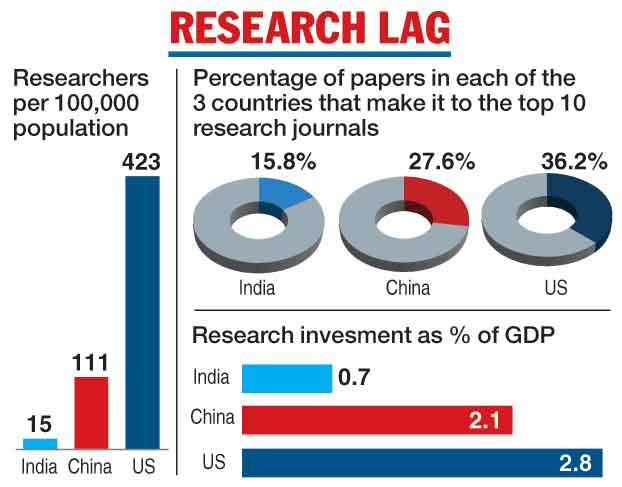

India has only 15 researchers per 100,000 population, compared to 111 in China and 423 in the US. Only 15.8 per cent of India’s research papers appear in the top 10 journals, compared with 27.6 per cent of Chinese papers and 36.2 per cent of US papers.

The Prime Minister’s Science Technology and Innovation Advisory Council (PM-STIAC) had in a project report on the NRF in December 2019 said that “an absence of integrated planning and coordination” was among the “impediments” to research.

While India’s multiple funding bodies supporting research across myriad fields have done “an excellent job in nurturing components specific to them”, the PM-STIAC had said, the lack of integrated planning and coordination means “the whole remains less than the sum of parts”.

India’s research capabilities are not likely to be realised through the existing structure by a mere increase in funding, the PM-STIAC report had said, outlining the rationale, scope, structure and objectives of the NRF.

The NRF would have 10 directorates — one each for natural sciences, mathematics, engineering, environmental and earth sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities, Indian languages and knowledge, health, agriculture, and innovation and entrepreneurship. Its research funds would be allocated across these directorates in ratios of 8:4:8:4:2:1:1:8:4:4. The PM-STIAC had asserted that these “suggested ratios” do not indicate the relative importance of the fields but the costs of research and absorptive capacities.

Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, who had announced the NRF in her July 2019 budget speech, had told Parliament in her February 2021 budget speech that the Centre had “now worked out the modalities and the NRF outlay will be Rs 50,000 crore, over five years”.

This figure was consistent with the budget estimates made by the PM-STIAC.

“Many of the NRF’s objectives overlap with those of existing agencies such as the departments of science and technology and biotechnology,” said Partha Majumder, a population geneticist and an executive member of the Indian Academy of Sciences.

“As long as the NRF budget is in addition to those of existing agencies, it would be welcome. But unless there is clarity in relation to those of existing agencies, there is room to doubt that the wings of existing agencies may be clipped,” he said.

“The outcome may be greater centralisation and subversion of autonomy,” he added.

Majumder and other scientists said they worry about centralised decision-making because it often results in, as Majumder put it, “erosion of collective thinking and collective decision-making”.

While the National Education Policy had proposed the NRF, it did not clarify how the foundation would coexist with the existing research funding agencies and funding mechanisms, said Gadadhar Misra, a mathematician at the Indian Statistical Institute, Bangalore.

Scientists point out that the Science and Engineering Research Board, established through an Act of Parliament in 2008, under the Union science and technology ministry is already tasked with funding research across many fields covered by the NRF.

“Are we replacing one agency with another — then why do it at all? We need clarity on this,” said Misra, who is among those wondering whether the NRF might translate into lower funds for other funding bodies. “Just creating a new agency will not address the impediments to research.”

Some are also concerned that the Centre has not signalled intentions to increase research funding. Its 2022-23 budget outlay for the departments of science and technology, biotechnology and industrial research, for instance, is 3.8 per cent lower than their initial outlay in 2021-22 and 5.3 per cent higher than their anticipated expenditure in 2021-22.

The 2022-23 budget outlay for the Science and Engineering Research Board is Rs 803 crore, about 10 per cent lower than its anticipated expenditure of Rs 900 crore in 2021-22.

“Some of us fear that once the NRF emerges, the support for other agencies will decrease — and funds will be concentrated with one agency,” said Soumitro Banerjee, a physicist at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Calcutta.

“This could have adverse effects on funding opportunities,” he said. “The diverse funding agencies currently have different priorities and if a proposal is rejected by one agency, scientists may seek funding from another. The second set of reviewers may find it worthy of support. But with one agency, that option may not exist.”