THE TRAIN

I love travelling by train. I would sit leaning against the window, watching the trees outside flying along backwards, fields spreading out, and rivers glittering past. A wish would often flow into me then. What if the journey would never end! A journey into timeless stretches, beyond the fields and rivers, into far distances, into eternity, without stopping…

I sometimes feel life too is like this train, cherishing a futile dream of journeying on for all times to come. But the train has to stop from time to time. Some of the passengers get out of the train at each stop, and new passengers come in, searching for vacant seats. At times, the departure of a person met briefly in the train leaves a long void. On occasion, the train stops at a station far beyond the expected time. But the train continues its journey.

In my childhood, there were several train journeys along with my Ummichi (mother) and Vappichi (father). Their hearts would be full of hope during each journey. The hope that, if we were to reach our destination, show me to the new doctor they had heard of, and follow his advice, I would get up on my legs and run around. It was during one such train travels that we met poet Kunhunni Master. I don’t remember anything about that meeting. I was too little a child. Ummichi would often narrate the incident to me. “It is quite possible you would one day become a great writer, Seba. Kunhunni Master himself had placed his hands on your head and blessed you.... He had predicted that you would become very famous when you grow up.”

I would lie awake in my berth long into the night, after everyone else had gone to sleep. Ummichi used to give me an inflatable pillow to place my head on. That pillow was a dear thing to me those days. Pressing my cheek on it, I would lie watching the play of light and shadows through the windows, as the train chugged along. When the train stops at a station, I would be eager to know where it had reached. I would listen for any mention of the name of the station by someone in the bogey.

Once, there was a journey to Kannur in the north. It was not a doctor whom we saw then. We entered a house where there were several people waiting in the verandah. When my name was called, Ummichi carried me in her arms and entered a room along with Vappichi. My elder brother Sejal Shah was with us then, and he too followed us into the room. It was an old man whom we met. He had a grey beard and a cloth wound around his head. I cannot remember his face after all these years. He was a musaliar (cleric). He asked Ummichi to lay me on a cot facing down. He chanted something in Arabic. Then I felt a sharp blade running over my back, making a shallow scratch on my skin. I didn’t know what was happening. I lay absolutely still, without showing my pain. The whole procedure might have taken about three minutes.

Sejal was full of wonder when we came out of the room.“Didn’t you feel any pain when that man stabbed you with his knife,” he asked me. To tell the truth, I was a little shocked when he put it like that. Stabbing with a knife! What a strange mode of treatment! But I didn’t show him my feelings. Instead, I gave him a smile, as though to tell him these were all nothing to me. Haven’t I handled tougher tests on my courage with perfect cool? I made a mental note that, in future, I would not allow any such “knife-stabbing” treatment on my body. Ummichi prepared a paste of several herbs prescribed by the musaliar and applied it all over my body every day.Vappichi went to Kannur from time to time to see the musaliar and report the progress. Subsequently, he decided not to continue this treatment for me.

From then onwards, my parents stopped going after every wild suggestion people around us would give them to treat me. If my memory is right, my last train journey so far in my life was on that visit to Kannur. The announcement over the public address system at Ernakulam Junction, alerting the passengers about the arrival of the Maveli Express, still rings in my ears:

“Attention passengers… Train number 16604, Maveli Express, will arrive on platform number 1, Ernakulam Junction, shortly”.

TRICYCLE MEMORIES

A few days ago, Ummichi reminded me of my old tricycle yet again.

I had a tricycle when I was a little kid. As soon as I wake up in the morning, I would climb onto it. Then I would go round and round all corners of the house. When we play hide and seek at home, I would go under our dining table pushing a chair or two into position and hide quietly to evade detection.

I cannot help smiling even now while imagining the craft with which I used to manoeuvre my tricycle. I used to spin the pedal with my left hand and expertly steer the handle with my right. They often speak about it with a great deal of amusement at home. We have a hearty laugh together whenever someone speaks about the wonder I was on my tricycle.

As soon as I get back from school, I would be on my tricycle, pedalling it towards our backyard where Vallyummichi (grandmother) had several plants growing. I would water the plants profusely and get merrily wet each evening.

Things were thus going on merrily for some time when certain changes transformed them almost overnight. My tricycle suddenly grew small. In other words, I was growing up. When I reached the third standard in school, I had grown too big to sit on a baby tricycle and ride. Soon I had to give up the tricycle for all times to come. It had helped me move around the house as I liked and I had loved it as a dear companion.

Subsequently, I came to use wheelchairs one after another, changing sizes, but was never again to experience the freedom of movement I had experienced when I was on my tricycle.

I asked Ummichi: “Do you know where my old tricycle is?”

Ummichi answered, rather casually: “It got all rusted long ago, didn’t it? We might have sold it as scrap.”

NESTING BIRDS IN MY HEART…

During one summer vacation, we went to the Government Ayurveda Hospital in Trippunithura (a municipality in Ernakulam) for me to undergo a month-long treatment procedure. From then on, we used to set apart one full month for this purpose every year.

Several new people came into my life during the days spent in the hospital. Vichu, Rohithettan, Aleetta, Gussy Aunty, Favaz, Sainathatha, Josootty, Aseela…

Every day, I would wait for the evening to arrive. Ummichi would roll me out of our room for a leisurely round or two along the corridors and open wards of the hospital floor, meeting friends and talking.

We can see the sun sinking into the greeneries far away from a particular corner of the corridor. We used to sit there on many evenings watching the sunset.

The treatment is during the forenoon hours. When that is over, we are all to ourselves. Whenever I feel boredom creeping over me, it used to be a pastime for me to watch the doves fluttering up and down the courtyard of the hospital and count the white doves among them. Occasionally, I can also see children in the rooms opposite mine coming to their windows to feed the doves with crumbs of bread.

One day, an elderly uncle staying in the next room asked me whether I knew how to solve sudoku puzzles. Without knowing what it was, I nodded my head with enthusiasm, as though to tell him I knew all about it. Uncle would have thought: Well, then let me put her in her place. He immediately searched out the day’s newspaper and cut out the portion of the page where the daily sudoku puzzle was printed.

Apparently, uncle and aunty had a high opinion about me. I did not want my image in their minds to take a dent. The whole night I sat over the puzzle, puzzling with numbers up and down the grids and reaching nowhere. When the morning came, I filled all vacant spots in the grids with random numbers and took the paper to uncle with the air of someone who had done it with complete ease.

The fact is, even though I didn’t know anything about the game, I would rather not admit my ignorance.

Uncle gave me a detailed tutorial on how to solve sudoku puzzles. He also advised me to never again claim I am an expert in a topic in which I am totally ignorant. I listened to him intently as he gave me his advice, feeling more and more embarrassed as he kept on talking. Rohithettan also came into the room and was listening to uncle. He too made fun of me.

After the sudoku incident, I became twice shy in all matters put to me. ‘I don’t know, I don’t know’ became my constant refrain even when it was about something I knew something about.

The last time I went for the ayurveda treatment, I think, was during the summer vacation after my eighth standard in school. That visit is full of warm memories. The duty nurse, a strict disciplinarian, wants all lights switched off at the stroke of nine. We will all switch off the lights just before nine and will be in bed waiting silently. The nurse walks down the corridor checking each room, the jingle of her bunch of keys following her each step. Things are back to normal once she has taken a full round and closed the main door of the hospital floor behind her. The jingle of the keys is not heard anymore.

Then there was a period of load-shedding in the place for halfan-hour from 9.30pm. As soon as the lights go out everywhere, inmates of all the rooms used to assemble in one corner of the corridor. Do you know what we used to do then? We would play the game of Anthyakshari. It is a game in which one participant first sets the ball rolling by singing two lines from a popular film song. The next player in the circle then has to take over by singing two lines from another song. The catch is that the first word of the song sung by the second player should be the same as the last word of the previous song. It tests the depth and spread of the player’s knowledge of film songs and is not meant for a novice in the topic.

We sing in hush-hush voices. But when the game hots up, voices are sometimes raised to higher decibels. Someone in the group immediately cautions everyone: “Hush! hush-hush! Don’t wake up the sister!”

Even today, when I hear the word Anthyakshari, I remember the ayurveda hospital. I remember its dark corridors smelling strongly of ayurvedic oils and, mistily, I remember several dear faces.

LENGTHENING DISTANCES

I always cherish the years I was a student in Alhuda Public School, near our home in Panayikulam. We children used to bring to school, in our instrument boxes, curios such as kuzhiyanas and green grasshoppers. Kuzhiyana means the pit-elephant, the elephant that lives in a pit. It is a little brown bug that builds small cone-shaped holes in the loose sands around the house and waits at the bottom quietly. When a wandering ant or lice slips into the hole, the kuzhiyana grabs it, overpowers it, and devours it little by little.

I had many friends in the school and I remember the fun and laughter we had together, and our little tiffs from time to time. The annual school youth festival, with many competitions for us, is a big event. I was a regular participant in poetry recital competition. The first half of my school life is full of happy memories.

I was five years old when my parents put me in the school. The headmaster told Ummichi to let me start from UKG. I had a special chair all to myself in the classroom. It was just the size for me and had hand-rests on which I could place a light wooden board and write comfortably. Ummichi would carry me on her hips every day and place me on my chair before the school bell rings.

Since my friends run around and play in the classroom when the teacher is not in the class, the position of my special chair changes from one place to another from day to day. It will be in the back row of the classroom one day, and in the front row the next day. On some days, one friend or the other would enter into a pact with me that we should sit side by side the next day. By the time Ummichi brings me to the school the next day, the chair would have been already moved to the preplanned position by the friend involved in the pact.

“Seba is sitting by my side today,” she will tell Ummichi at the door, showing the spot where my special chair is currently situated. I will sit with many friends in the class by turn. I can sit anywhere, unlike my friends who have fixed positions in the classroom.

When I was new in the school at the UKG stage, our teacher used to carry me on her hip, like Ummichi, and place me in a convenient spot in the open corridor outside the classroom during playtime. I could watch my friends making merry on the swings and seesaws and slides in the play area. Now and then, a friend would break out of the game and sit by my side, talking like we children do.

Something unfortunate happened one day. Some of the boys were playing touch-me-if-you-can in the corridor and one of them accidentally touched me, sending me tumbling down from the verandah into the ground. Though there was no injury, I made a big scene, crying inconsolably. From that day onwards, the teacher stopped taking me outside during playtime. I would sit in the classroom alone while everyone else went out to play. Once in a while, a friend would come and sit with me. I learned to be comfortable alone with a book on my lap, not necessarily reading it or looking at the pictures.

Ummichi was finding it difficult to carry me to school as time passed. She started developing back pain. By the time I reached the third standard in school, Vappichi built a little house very close to the school near Puthenvelipparambu, where Uppappa’s (grandfather) ancestral home is located. There is a backdoor for our bedroom. Just a few steps away is a compound wall with a gate. If you open the gate, you can enter the long verandah on the backside of the school building. Ummichi could easily roll me in a wheelchair from our home to the classroom.

Till then we were living in my grandparents’ home a little distance away. Ummichi had been carrying me to school. Now my movement was on a wheelchair. When we reach the classroom, Ummichi would place me on my special chair. At times, my friends would help her. My special chair was getting too small for me and soon it became too cramped for me to sit on. By and by, I found myself sitting in the wheelchair itself in the class.

The place of the wheelchair was, however, by the side of the teacher, away from the rest of the class. I had to place my books on the teacher’s table so that I can write. It felt as though the distance was lengthening between me and my friends.

NIGHT RAIN

It was approaching sunset time, but night had already come. Outside my window, rainclouds had gathered in the sky, building up a storm.

I was alone in the room. The last two days, I could not eat food, nor drink a glass of water. Only saline water and some medicines entered my body along an IV canal, which dangled by my bedside, ticking drop by drop.

It started raining. There was a pattering of raindrops on the roof, and then, with a sudden rush of monsoon winds, heavy downpour. The sorrow that had been building up in my mind, till then holding back somehow, also came pouring down. I was crying.

Sugathakumari Teacher’s poem, Night Rain, came to my mind. I had memorised the poem to sing it on the stage at our school youth festival, when I was in the tenth standard. After the youth festival, I had forgotten all about the poem. Now I tried to pick up the lines from memory.

Night rain

— for no purpose crying, laughing,

sobbing,

muttering incoherent

nothings,

bent on her knees,

swishing her tousled

tresses on the floor —

a young woman, in the throes

of insanity...

The poem came back to me as though I had learned it by heart only yesterday. I recited the poem silently, picking each syllable from memory, as I listened to the tumult of the rain and wind outside. Now the poem revealed to me depths of feelings that had eluded me all along.

The other day, some old friends had come to see me in the hospital. Since I was in and out of the hospital very often, not many people came visiting me nowadays. I was lying with my eyes closed, pretending to be asleep, seething with a nameless anger, perhaps against myself. The moment I heard Sana’s voice in the corridor, I opened my eyes and looked at the door.

Sana is only one of my many friends from early childhood. Our special bond is because both of us had the same ambition in our tender days. We wanted to become world-renowned scientists when we grew up. We were to be found cooped up in some corner of the classroom very often, discussing scientific matters like rockets that travel to the moon. Everyone used to make fun of us in the class, calling us scientists. However, after the tenth standard, I had joined the commerce stream of higher secondary education. My parents were against my going for the science stream, saying that it would be difficult for me because of the practical work involved.

I was overjoyed when I saw Sana, Jahana and Shabna walking into the room. They sat with me for a long time talking about a lot of things, our times in school together, and how they were getting on with their new friends. They left after promising me they would certainly come to see me again.

I was thinking of all these when Ummichi returned to the room after buying certain medicines from the hospital pharmacy. The rain had subsided. I asked Ummichi to sit by my side. I recited to her the poem Night Rain, just as I had sung it on the stage in school.

Sleep came over me in dark waves. Hunger, weariness, total exhaustion. Gloom enveloped me like a warm blanket. The rain resumed and continued into the night. At least for one brief moment that night, while swinging between sleep and dream, I think I wished I would not wake up from that sleep.

THE SEA

“How long has it been since we last went to the beach,” Ummichi said with a sigh.

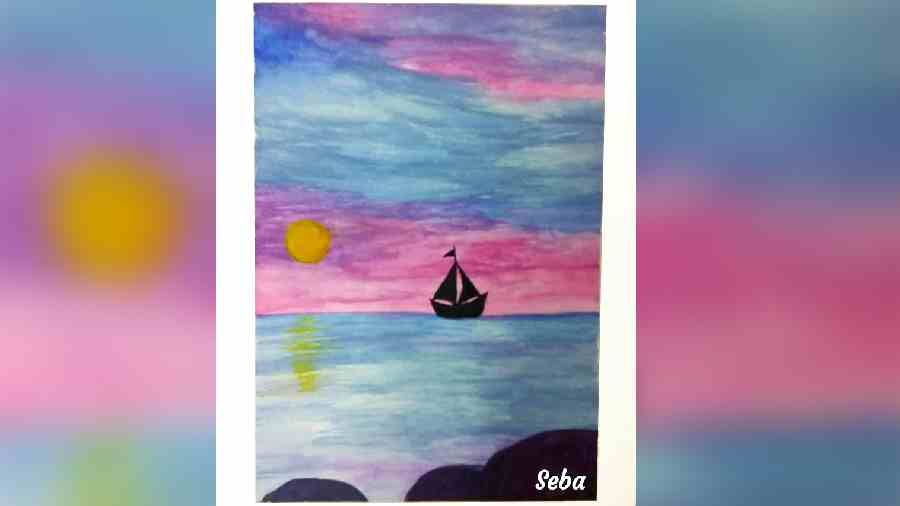

“Well, isn’t it to see the sea whenever we want to, Ummichi, I had painted this picture and kept it by my bedside?” I asked her. Sometimes I can crack a joke, but she didn’t smile.

It was to Cherai that I went to see the ocean for the first time. Cherai is about fifteen kilometers from Panayikulam, where we live. Taking my wheelchair to the seaside over the beach sands was pretty difficult those days. The wheels get bogged deep in the loose sands.

Vappichi and Elaappa (uncle) took hold of the chair from either side and virtually sprinted down to the seaside laughing, without giving the wheels time to even think of sinking into the sands. I was overjoyed that day watching the waves roaring in and several paper kites flying high in the sky. I had a kite in the sky with its thread tied to the hand-rest of my wheelchair and I was gazing at the setting sun. Ummichi placed a packet of roasted peanuts in my hands. I turned my eyes to the packet and sat looking at it for some time. Then I carefully took the peanuts one by one to my mouth.

The Sea. Water colour painting by Seba Salam

A few moments later I felt as though some mischief was afoot. When I looked around, I saw Elaappa, Sejal Shah and Richu recording a video of me eating peanuts. I smiled into the camera and turned my attention once again to the peanuts, without appearing to be self-conscious.

Later, when I was studying in the eighth standard, we went to Cherai once again. It seemed to me the place had undergone a complete transformation. Now there was a pier with a ramp for wheelchairs leading to an elevated platform facing the sea, some distance away from the shoreline. I sat there for a long time and watched the sea and the beach.

I remembered the stories of mermaids I had read in my childhood…

Who knows? There could be a mermaid hiding in the shadow of the waves, scanning the people on the beach for her Prince Charming. The beach was suffused in the golden glow of sodium vapour lamps. There were children with their parents and groups of merrymaking friends on the beach and paper kites fluttering in the breeze. The mermaid had known only the darkness of the deep seas. How marvelous it would be, if, in her next birth, she was like those children playing on the beach.

One day, I saw a video of Sue Austin in her TED talk. She is in a wheelchair and she is diving into the depths of the sea like any expert scuba diver. I showed the video to Ummichi. She was also struck with wonder. I felt respect for the lady who pursued her desire for 360-degree freedom of movement even in a wheelchair. She achieved her dream through sheer determination and there she was, taking her wheelchair along those wonderful sights of deep-sea corals and swarming fish...

Some people are like that. They will go after their dreams notwithstanding anything and make them come true too. Such people are a great inspiration for me.

Stephen Hawking is another character lighting up my skies. I can’t remember when I first heard about him. From the time I can remember, Ummichi used to show me his photos whenever they got printed in Malayalam newspapers. I didn’t know anything about him other than that he was a scientist sitting in a wheelchair. All the same, I began to cherish the dream of becoming a scientist like him when I grew up. When I was studying in the nineth standard, we visited a doctor to receive the certificate required for getting approval for writing exams at school with the help of a scribe. The doctor asked me: “There’s a famous scientist living with a motor neuron disease, like you, Seba. Do you know him?”

It was only then that I came to realize that spinal muscular atrophy is a motor neuron disease. I had never ever seriously thought about my illness when I was a kid. When Elaappa sent an email to a doctor working in Mumbai asking certain questions regarding my treatment, I was the one who translated it into Malayalam for Ummichi. Even then I didn’t memorise the details about my disease written in the email.

My mind is always filled with thoughts centred around little things. I will laugh and also weep for little reasons. Have you noticed the waves of the ocean? They roll in and thrash their heads on the shoreline and withdraw all by themselves, dissolving in the waves that roll in from behind. I used to feel that my thoughts are just like those waves. They are with me when I’m awake and also when I’m asleep. They take me floating alternately over my little world of memory and oblivion.

● Translated from Malayalam by P. Venugopal

Copyright: Seba Salam