Fast, accurate and systematic detection of Covid-19 positive cases, their isolation and cure are the backbone of the strategy to break the transmission chain and contain the coronavirus pandemic. This emphasis was unequivocally communicated by the WHO director-general on March 16 when he said: “We have a simple message for all countries: test, test, test. Test every suspected case.”

Unfortunately, India has been slow to evolve its testing strategy, driven partly by official complacency regarding the efficacy of the lockdown and to an extent by the constraints on timely procurement of Covid-19 testing kits and PPE (personal protection equipment), amidst a global scramble.

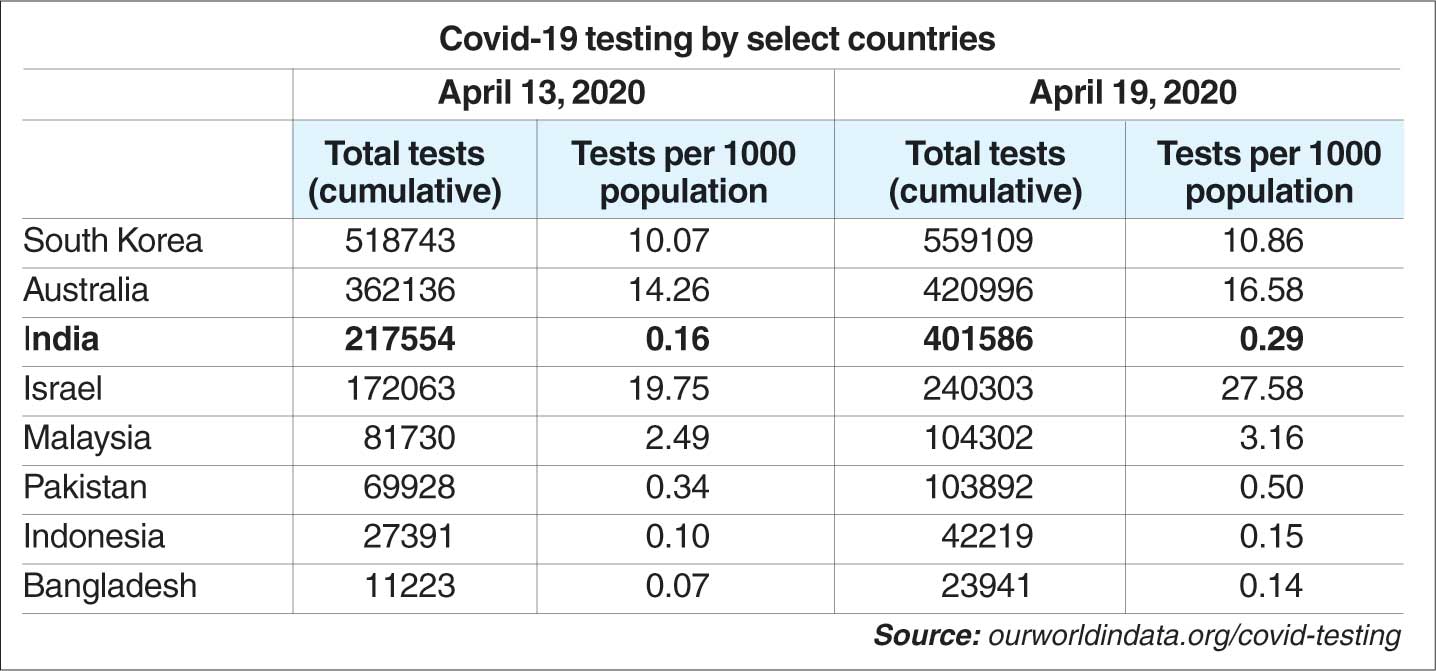

As a result, India could not emulate the successful examples of early containment of the pandemic through speedy testing and contact tracing, which has been possible in South Korea, Australia and the United Arab Emirates. India lagged behind many countries in utilising the first phase of the lockdown to rev up its Covid-19 testing rate.

Till April 13, India had tested a total of 2.17 lakh samples from 2.15 lakh individuals, with an average testing rate of below 16,000 samples per day from April 1 to 13, according to the data released by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). It is only after the extension of the

nationwide lockdown on April 14 that the testing rate in India has seen a significant increase to around 30,000 per day.

In terms of tests per-capita, India still ranks behind most countries.

While the ICMR is only releasing aggregate all-India-level Covid-19 testing data, that too in an irregular manner, the state-wise testing data is not being released centrally, either by the ICMR or the Union health ministry.

Moreover, there are discrepancies in the aggregate data on active Covid-19 cases being released by the ICMR and those being displayed in the Union health ministry dashboard.

Data reporting in India is still being done on a cumulative basis, whereas the WHO-recommended format requires reporting of new tests, new confirmed cases, new recoveries and new deaths, along with their age and gender-wise break-up. The all-India and statewise (Top 20) cumulative testing data for April 18 show that the top five states — Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat — accounted for over 50 per cent of the tests conducted in the country till April 18.

Kerala has, of course, led the way in testing and contact tracing, becoming the first Indian state to flatten the curve of new confirmed cases.

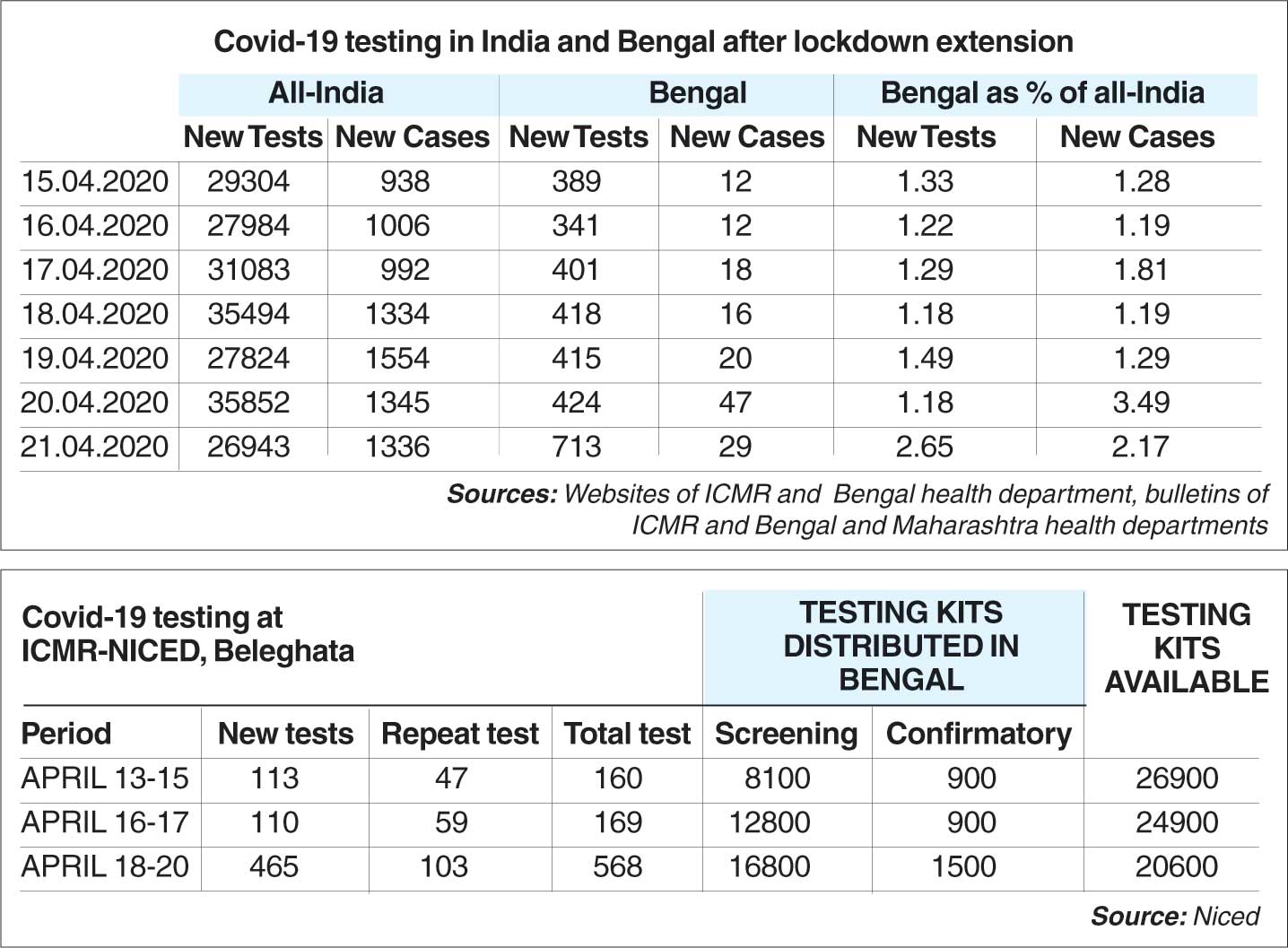

Bengal has been lagging way behind most others in testing and it has the worst per capita testing rate in the country. Only one out of every 20,000 people in Bengal had been tested for Covid-19 till April 18, when the all-India average was already above five.

Calcutta High Court had admitted writ petitions questioning the state’s handling of the pandemic on April 17 and asked the state government to report its “adherence to effective screening on war-footing” and “acceleration of the rate of sample collection and testing”.

Since the extension of the lockdown, new Covid-19 cases are showing an upward trend both for India as a whole as well as for Bengal. This makes an enhanced rate of testing an imperative for the entire country, particularly for Bengal, which has averaged less than 2 per cent of the daily tests conducted across the country from April 15-21, despite being home to over 7 per cent of the Indian population.

Despite the presence of a modern laboratory like the Virus Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (VRDL) at ICMR-NICED located in Calcutta’s Beleghata, its capacity is not being fully utilised to increase Covid-19 testing in Bengal. This is obvious from the testing data released by the ICMR-NICED so far.

There is ample scope for increasing the pace and rate of Covid-19 testing at the VRDL during this time of crisis. There is an existing inventory of over 20,000 testing kits in Bengal, which can also be utilised to accelerate testing.

Moreover, the Bengal health department has publicly complained about the quality of the testing kits being supplied by the ICMR-NICED, which are “resulting in a high number of repeat/confirmatory tests and causing delays and other attendant problems”. This is an issue that the ICMR needs to resolve expeditiously.

While importing testing kits from China to meet the immediate crisis, the Indian government must explore domestic production of high-quality testing kits to meet future exigencies.

The slow rate of testing in Bengal can certainly be attributed to the unfortunate political bickering between the Centre and the state government at a time of a public health emergency. If adequate testing becomes a casualty in the process, infections will remain undetected in affected clusters. This will either slide Bengal into the hellhole of community transmission or perpetuate the suffocating lockdown longer than necessary, inflicting massive socio-economic pain. In order to prevent such horrific scenarios, stop politicking, just “test, test and test”.