Sometime in the late 2000s, a young software engineer who voluntarily ran social media propaganda for the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh and the Bharatiya Janata Party got an opportunity to attend a BJP social media meet in Bangalore. Among the people who saw this young man speak there was the then Gujarat chief minister, Narendra Modi. “Why don’t you do something for me,” Modi said to him, encouraging him to promote Modi on social media. Around the same time, the Congress party was telling Shashi Tharoor to go easy on Twitter.

Today that young man is arguably one of India’s most important people, part of a select group of people informally used by the top echelons of the ruling party and the government to influence the online narrative. He’s regularly trying to make this or that trend

on Twitter, running WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages that reach millions of people. When he met Modi during the 2014 campaign, the PM-to-be told him, “Keep it up. We have to make mainstream media irrelevant.”

A fragmented audience

It is difficult today to think of elections without social media. We now have the opposite problem of overestimating its impact. While 35 per cent Indians have access to the Internet, 66 per cent have access to television. TV news remains the most important medium for politicians to reach out to voters, and it’s not just because of the numbers. TV news is not as fragmented as social media. It helps you give a uniform message that can get lost in the social media noise.

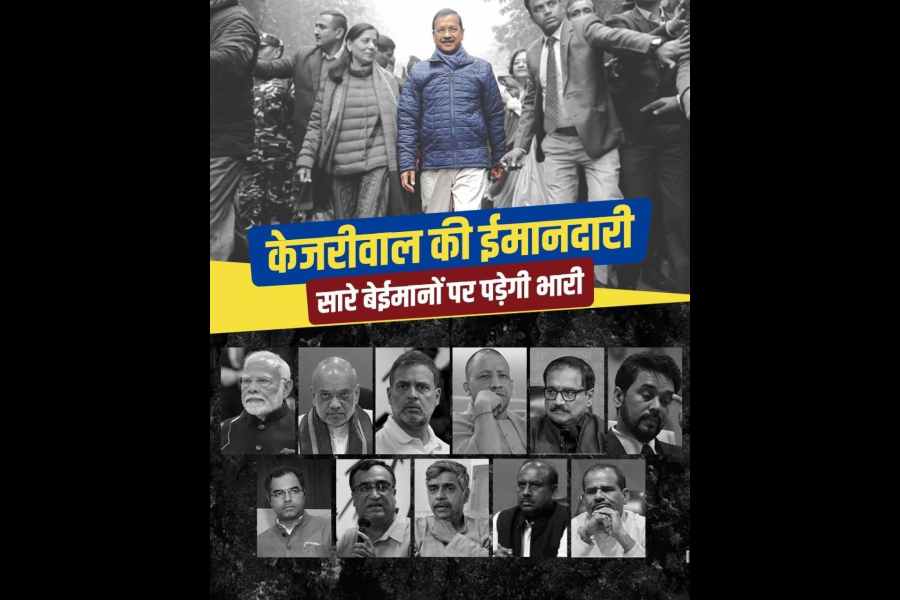

The fragmented nature of social media has its own uses nevertheless. It allows parties to offer different narratives to different audiences. It allows, for instance, BJP to offer extreme Hindutva on a WhatsApp group targeted at a district in Uttar Pradesh and a narrative of, say, development and progress to an urban, elite audience on Twitter. Fragmentation also allows you to micro-target audiences.

Ear to the ground

It is a myth that politicians use social media only for propaganda. There’s another very important purpose it serves them: feedback. There are people working full-time on this. The job description is “communication observer”.

Myriad “sentiment analysis” software are available to trawl through vast amounts of social media content and study public mood on a regular basis.

Social media is also used by politicians as a sounding board. Trial balloons are floated on it to see how different audiences respond to a particular idea. If the response is good, expect it to become policy. In the past, politicians used to put out such feelers through the press; today, they do it through their online armies.

Breaking through the filter bubble

Social media runs on algorithms that give you more of what you want, keeping you glued to their platforms. The algorithms thus feed confirmation bias and make sure you stay in the comfort zone of your filter bubble. Even without the aid of algorithms, people tend to follow personalities and topics that conform to their political inclinations. The social media filter bubble aids polarisation, making it difficult to persuade voters to change their inclinations.

For voter persuasion, traditional media still works best. Even better is face-to-face interaction. Party workers and cadres going from door to door establish a real connection, assuring people they are being heard.

Voter persuasion, in any case, is best achieved by a politician’s actions. The morning paper, the evening TV debate or the visual meme on WhatsApp are the only distribution tools that can amplify the politician’s voice. Social media by itself doesn’t make Narendra Modi own the national security narrative; the Balakot air strikes do. The promise of a minimum guaranteed income may swing some voters towards Congress, even if they see too many jokes deriding Rahul Gandhi on their Facebook feed.

Breaking through the filter bubble is somewhat possible by attracting people through specific issues and interest areas. A party might create a WhatsApp group or a Facebook page in praise of the Indian Army, and just before elections, the page might tell its engaged audience which party is best for the army. This is why there are digital armies of political parties running online pages about Bollywood, desi humour and even soft porn!

Content is king. Distribution is god

Make no mistake: social media as a distribution channel is very important, if only to reach out to your own supporters. Narendra Modi built and exploited this channel to reach out to BJP core supporters and voters, helping create the demand for Modi as the party’s prime ministerial candidate. Let’s make mainstream media irrelevant, he told that young volunteer, because he felt the media wanted to keep him trapped in his 2002 image. Social media lets you define yourself. You are no longer to be defined by the questions journalists choose to ask.

The Opposition has faced a similar dilemma in the last five years. Much of media, particularly TV, has been openly partisan in favour of Modi and the BJP. The Opposition has been slow and late in creating the distribution channels, even though it’s an inexpensive option as compared to traditional media or outdoor campaigning. Modi is always two steps ahead of the Opposition on social media. Having made the mainstream media irrelevant, he wants to go a step further and make social media platforms irrelevant. He wants you to see, hear and read him on his own NaMo app.

Content is king, the saying goes, but distribution is god. Through Facebook advertising and countless WhatsApp groups, innovative campaigns and daily Twitter trends, the Modi machine makes sure everyone gets to hear what it has to say. At one point BJP asked its Lok Sabha MPs to gain three lakh genuine followers on Twitter if they wanted a shot at getting the ticket again in 2019.

Having your own social media distribution channels in place helps you to create the perception that you are dominating the narrative. Tagging celebrities on Twitter or asking people to use a hashtag, Narendra Modi is able to fulfil his objective of always having people’s attention on himself. This becomes particularly crucial in elections where parties need to create the perception they are winning to influence the fence-sitting voter.

“See this meme I got on social media,” a voter told me during the Gujarat 2017 Assembly elections, “In 2014, it was unimaginable that anyone could speak like this about Modi!” With this he deduced that BJP wasn’t doing too well in the elections — and he was nearly right.

Gather your troops

The global benchmark for the use of social media in elections remains the Barack Obama campaign of 2008. Known as the “Facebook election”, that campaign quietly built a groundswell of support for Obama among young voters, taking him from a relatively unknown political figure to President.

Key to making this happen was to gather supporters using social media. Since social media is a filter bubble, it may not

help you convert a Republican into a Democrat but could help Obama become popular among Democrat voters. Once that is done, social media lets the campaign pick out enthusiastic supporters and make them volunteers.

We know from moments like the 2011 Arab Spring what a marvellous mobilisation tool social media is. Before the 2014 elections in India, the Aam Aadmi Party and the Modi campaign both used the Internet to create armies of online and offline volunteers.

In the 2014 Modi campaign, the young professionals of the Citizens for Accountable Governance (CAG) — the Prashant Kishor-led political action committee — were tasked with making Modi look like a larger-than-life figure. The CAG made constituency-specific Facebook pages named “Narendra Modi for (constituency name)” to attract Modi supporters in every constituency. The page would then ask these supporters to become volunteers. Thousands of volunteers were thus recruited across India, and given online and offline tasks to carry out, such as helping organise “Chai Pe Charcha”. Here is one of the many tasks they were given: take a return train to anywhere, chat up fellow passengers and tell them of the great work Modi has done in Gujarat. Similarly, AAP has found volunteers online just to make them call voters on phone through an online database of voter phone numbers. So they had NRIs from the US call up voters in Delhi slums for voter persuasion.

Gathering passionate volunteers who help you for just a few weeks during elections

is something Modi does even now. The big Modi campaign on Facebook, called “Nation with NaMo”, and the Narendra Modi app have both been asking for volunteers. These volunteers bring raw energy that digital marketing agencies or career-seeking party workers can’t match.

Who’s afraid of fake news?

Fake news gives people what they already want to hear, and is thus largely ineffective in winning over new voters. Fake news is best for keeping up the morale and enthusiasm of your own supporters and voters. Retaining your existing voters is very difficult, especially for a politician in power.

While fact-checking is important for democracy, fake news will continue to spread like wildfire inside social media filter bubbles. It is good enough to see what narrative a piece of fake news is trying to spread, and then find strong ways to counter that narrative.

If there’s one thing that travels faster than fake news, it’s humour. Parties produce so much humour for social media these days that we are left laughing at our WhatsApp forwards all day. In the 2014 elections, there was an endless supply of fresh Pappu jokes ridiculing Rahul Gandhi. By 2015, the supply of these jokes curiously stopped. The reason was that these jokes were being produced by Prashant Kishor’s CAG which disbanded soon after the election. It was called carry out negative campaigning without being blamed for it.

Medium is the message

If 2014 was India’s Facebook election, 2019 is the WhatsApp election. Twitter battles are fought daily by parties mainly to influence

the media and the intelligentsia. The growing vernacular app, Sharechat, is a library of memes in regional languages. The video app, TikTok, is the fastest growing new phenomenon in parties.

Before you can master one platform, another one rises. The key platforms are already undergoing a transformation from vitality to engagement — Facebook and Twitter both want to emphasise conversation over mass reach. Like everyone else using social media, politicians too need to chase the social media attention rabbit wherever it goes. In the end, the politicians who use social media the best are the ones who keep abreast with the trends themselves, taking first-hand interest in the medium and the message alike.