Poor skills or substandard care provided by doctors or healthcare facilities accounted for a third of instances of medical negligence examined by India’s apex consumer court over a five-year period.

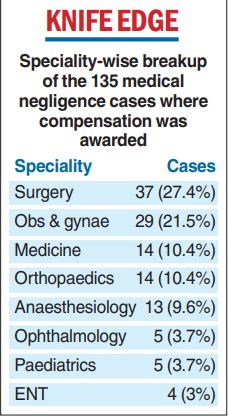

A study of medical negligence cases at the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC) has also found that five specialities — surgery, obstetrics-gynaecology, medicine, orthopaedics and anaesthesiology — made up nearly 80 per cent of the cases where compensation was awarded for negligence.

The study, the first systematic analysis of the frequency, seriousness and causes of medical errors, noted that many instances involved a lack of infrastructure, flawed consent forms, or missing medical records.

“Research on the nature of errors could provide insights into what can be fixed and which areas we need to focus on to minimise their risk,” said Sanjay Sukumar, a forensic medicine specialist at the Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medicine and Research in Puducherry who conducted the study.

The NCDRC had awarded compensation in 135 (53 per cent) of the 253 medical negligence complaints it had reviewed from 2015 to 2019, according to the study, published in the peer-reviewed Indian Journal of Medical Ethics on February 18.

Surgery made up 37 (27.4 per cent) and obstetrics-gynaecology accounted for 29 (21.5 per cent) of the 135 cases where compensation was awarded. Medicine and orthopaedics accounted for 14 (10.4 per cent) cases each and anaesthesiology for 13 (9.6 per cent).

A lack of skill or care was the most common reason for such litigation, accounting for 62 (36.3 per cent) of a set of 171 cases where some error was established. This was followed by 38 (22.2 per cent) cases involving deficiencies in the maintenance of medical records, and 18 (10.5 per cent) cases of poor post-operative care.

In connection with the gaps in medical records, Sukumar said, the NCDRC observed that “poor records mean poor defence, no records mean no defence”.

A poorly crafted consent form that does not mention the risks involved in a procedure also constitutes a deficiency in service, he said.

Many of the errors, Sukumar said, could have been prevented. For instance:

- The transfusion of a wrong blood type to a woman who had just delivered a baby led to the death of her foetus in a subsequent pregnancy

- An invasive, avoidable procedure was performed on a patient with severe pancreatitis, leading to fatal complications.

- An infant was administered an intravenous channel that led to gangrene of the hand, which had to be amputated.

- A nurse administered an anaesthetic agent, leading to the death of a patient. The drug should have been administered under the supervision of a doctor

- An appendectomy was followed by intra-abdominal haemorrhage that was attributed to poor surgical skill and substandard post-operative care.

Sukumar has in his study called for formal error-reporting systems at healthcare institutions, more research on medical errors, and the use of NCDRC cases to impart lessons to medical students, doctors and faculty.

The study emerged from an effort by Sukumar to use NCDRC case files as examples while teaching undergraduate and postgraduate students in his college.

“I hope such real-life cases will help students grasp the potential for medical errors better than theoretical discussions,” he said.

Sukumar and other doctors said the study’s finding that compensation was not awarded in 118 (47 per cent) of the 253 cases the NCDRC reviewed also suggested that many complaints of medical negligence are filed without merit.

“We know that many patients who are aggrieved or dissatisfied approach the consumer courts without really going into the merit of the case,” said Manish Machave, chair of the ethics and medico-legal panel of the Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of India. “It is quite easy to file a case.”

Sukumar’s study has documented the highest and the average compensations awarded by the NCDRC across medical fields.

In surgery, the highest award was Rs 47 lakh and the average Rs 8.3 lakh; in obstetrics-gynaecology, the highest was Rs 1.1 crore and the average, Rs 9.9 lakh.