Kirti Pathak, fourth-year medical student at Kunming Medical College, is not worried about returning to her college in China after the Covid-19 pandemic blows over, border faceoff or not.

“Everybody has always been very friendly there; the teachers are very helpful,” she said from her hometown Jind in Haryana, where she had arrived during a semester break in January before being stranded by the pandemic.

What she is worried about is the Foreign Medical Graduate Exam (FMGE) that she will need to take once she graduates and returns from China.

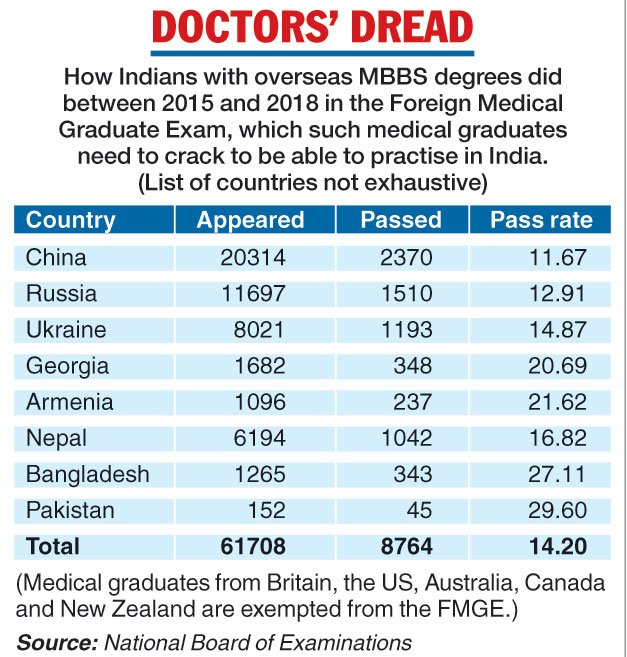

Over more than a decade, the pass rates have been abysmal in the exam that all medicos graduating from foreign countries — except for a few English-speaking nations -— need to crack if they want to practise in India.

Between 2015 and 2018, the pass rate for the 60,000-odd examinees has been 14.2 per cent; while the 20,000 from China among them have fared even worse at 11.67 per cent.

Some senior doctors blame the “poor standards of medical education” in countries like Russia and China and question the quality of the Indian students who fail to bag MBBS seats at home and choose to study in these nations.

But the young doctors complain — with some support from peers and professors — that the FMGE is an inexplicably tough exam of “PG-level difficulty”, and an “opaque” one that does not provide the answer keys.

Dr Raghu Ram Nayak from Nizamabad, Telangana, says he cleared the FMGE in June 2018 in his seventh attempt since 2012, the year he earned his medical degree from Ukraine. “It was tough,” Nayak, 31, said.

And yet, he said, he cleared the NEET PG — the all-India postgraduate medical entrance exam that is conducted, like the FMGE, by the National Board of Examinations — at one go in January this year.

He took the exam after clearing the FMGE and doing a year’s internship, and is now participating in the counselling process that will decide where he will be enrolled.

“I found the FMGE a far tougher test than the NEET PG. They have deliberately made it tough to fail more students,” Nayak said.

Would-be doctors travel to countries like Russia, China or Ukraine to study mainly because India hasn’t enough MBBS seats to meet the demand.

The country has 519 medical colleges that can admit 80,312 MBBS students a year, junior health minister Ashwini Kumar Choubey had told the Lok Sabha on November 29, 2019. About half these seats are in private medical colleges.

Dr Baibhav, a young Mumbai-based doctor, said Indian students go to these countries because they can complete their six-year course there within a budget of Rs 30-40 lakh, whereas even the cheaper private colleges in India charge nearly double.

Kirti’s tuition fees over six years, for instance, will be Rs 21 lakh and she says her other expenses would come to around Rs 10 lakh.

Quality concerns

Dr T.S. Satyanarayana Rao, a Mysore-based doctor, said the “miserable” 11.67 per cent pass rate among students with Chinese degrees meant the “quality of education is very poor in China”.

“People are gradually realising it. I’m sure the students’ flow from India would come down sharply,” Rao said.

Dr Sanjay Gupta, professor of psychiatry at Banaras Hindu University, appeared to blame the abysmal FMGE pass rates on mediocre students facing an “additional burden” they were ill suited to shoulder.

He said that Indian students enrolled in Chinese institutions because they were unable to secure seats in an Institution of their choice in India.

And then they faced the “additional burden” of dealing with the “cultural dissonance and stress associated with a foreign land” apart from having to clear an extra examination (FMGE).

‘Opacity’ charge

Dr A. Nazeerul Ameen, president of the All India Foreign Medical Graduates Association, who earned his medical degree in Russia, alleged the FMGE was too “opaque” an examination.

“The questions are of postgraduate level, and the answer keys are not made public, unlike other national-level tests. There’s a need for greater transparency,” Ameen, who did his MBBS and PhD from Russia in the 1990s, said.

He said the FMGE was introduced in 2002. Earlier, the Medical Council of India automatically recognised the degrees awarded by foreign medical colleges that it recognised.

Ameen asked how the pass rates in the bi-annual FMGE could fluctuate so wildly if the exam were transparent — from 3 per cent in July 2003 to 77 and 58 per cent in September 2005 and March 2008, while mostly staying within 10 and 30 per cent.

“We have a strong suspicion that the MCI is influenced by the lobby of private medical colleges, which is against allowing qualified doctors from abroad to practise in India,” Ameen said.

Nayak said: “Each time I failed the FMGE, where a candidate needs to score 150 out of 300, I fell short by three marks, five marks or seven marks. I too have strong suspicions about transparency in the exam.”

Nayak has another grouse. After failing the FMGE several times, he had returned to Ukraine in 2016 to earn a postgraduate degree in general surgery.

Now, after clearing the FMGE, he is again looking to enrol for a PG degree in India because the MCI does not recognise his postgraduate earned in Ukraine.

“The Dental Council of India holds two different screening tests for Indian students with undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in dental surgery from foreign countries, but the MCI holds only one — the FMGE — for MBBS graduates from abroad. Why does it not have a test to recognise the master’s degree?” Nayak said.

Dr Baibhav said he had heard it many times within the fraternity that the FMGE was a very tough exam.

He cited another “discrimination” — Indian students with foreign MBBS degrees can seek PG admission only after clearing the FMGE but foreign medical graduates from these same countries can directly appear in the NEET PG and enrol in a private medical college in India.

Separate emails sent to MCI secretary-general Rakesh Kumar Vats and NBE president Dr Abhijat Sheth on June 22 to seek their reactions have evoked no reply.

H. Chaturvedi, alternate president of the Education Promotion Society of India, the national body of private professional institutions, admitted issues with the FMGE but ruled out any conspiracy by any private lobby.

“There may be problems with the design of the test, which can be addressed by the conducting body,” he said.

Chaturvedi suggested the proficiency of the foreign medical graduates may suffer a little because they have to learn a new language to talk to the patients at their overseas medical college.

He had a suggestion: “Most Indian doctors are not interested in working in rural areas. The FMGE test must look at the doctors’ dedication to serve in different areas.”

Dr Harjit Singh Bhatti, national president of the Progressive Medicos and Scientists Forum, said he had learnt from his colleagues that the FMGE question paper was indeed very tough.

He agreed that the poor pass rates suggested the difficulty level had been kept high to discourage would-be doctors from enrolling abroad.

“I have many friends who have done their MBBS from Russia, Ukraine and China. The education transaction is much relaxed there. But that does not justify the 14 per cent pass rate. The NBE should test only the basic understanding of the candidates,” Bhatti said.

Asked about the allegations of private colleges influencing the exam’s difficulty level, Bhatti said these accusations may be gaining strength because of the government’s recent policy decisions in favour of the private sector in higher education.

Neeraj Chaurasiya, education consultant and CEO of MBBS Gurukul Abroad Admission Consultancy, said Indian students enrol only in those foreign medical colleges that are recognised by the MCI, the medical education regulator.

These colleges teach every student, foreign and domestic, in English. Chaurasiya said China has 45 such institutions, which offer 3,400 seats to international students. Of these, nearly 2,000 are taken up by Indians every year.

“These Chinese colleges admit Indian students based on their score in (India’s) NEET and an interview conducted on Chinese multi-purpose messaging and social media platforms like WeChat,” he said.

Kirti says she is already preparing separately for her FMGE along with her “regular course studies”. She will take the exam in 2022.

“My online classes started in March-end through WeChat, QQ and the Superstar apps,” she said.

“My university has decided that no student will be allowed to return till everything in the world is stable and safe.”

Hemant Adlakha, a professor at the Centre for Chinese Studies in JNU, said Beijing was unlikely to block Indian students’ entry because of the standoff with New Delhi.

“Chinese policy is clear that the Galwan Valley incident will have no bearing on India-China relations. In fact, they may encourage more people-to-people relations,” he said.

Furqan Qamar, former secretary-general of the Association of Indian Universities, which accords equivalence to degrees obtained from foreign universities, said the balance of student flow between China and India now hugely favoured China.

Quoting foreign ministry data, he said 18,171 Indian students studied in China and another 500 in Hong Kong in 2018. In contrast, the All India Survey of Higher Education 2018-19 counted only 106 students from mainland China and 7 from Hong Kong pursuing higher education in India.

Qamar felt the Covid-19 crisis would drastically reduce the flow of Indian students to China.