The JDU in Bihar has chosen as the central theme of its campaign for the Assembly elections later this year a comparison between the “good governance” during 15 years of Nitish Kumar’s rule and the “anarchy” during the 15 years of Lalu Prasad.

The JDU, which runs the Bihar government in alliance with the BJP, decided at a meeting of its top office-bearers that was chaired by Nitish on June 29 that its campaign would revolve around “explaining” to the voters the “fundamental difference” between Nitish’s “susashan” and Lalu’s “jungle raj”.

The JDU second-in-command, general secretary (organisation) R.C.P. Singh, who shares with chief minister and party boss Nitish the same caste (Kurmi) and native district (Nalanda), is in charge of propagating the theme through four sub-committees that have begun doing the job through videoconferences and social media.

RCP, as former IAS officer Singh is commonly known, on Tuesday interacted with the students’ wings of the JDU via video. The party aims to reach out to young voters through the Tuesday Talk and Mangal Shiksha Samvad (Pious interaction on education) campaign.

Closer look

An analysis of empirical data exposes the chinks in the JDU’s theme. The JDU’s claim that RJD chief Lalu’s 15 years — as chief minister from 1990 to 1997 and then his wife Rabri Devi as chief minister from 1997 to 2005 — were marred by “all-out anarchy” and Nitish’s 15 years, from 2005 to 2020, represented “susashan” is fundamentally flawed.

The records show that Lalu performed phenomenally well, bringing about major change in the living standards of the poor during his first term (1990-95) — not only through empowerment but also in material terms. To his credit, Nitish too did reasonably well in his first five years (2005-2010). After their respective first five years, both prioritised politics over governance.

Lalu, after taking over as chief minister in March 1990, had introduced schemes that brought about a fundamental improvement in the living standards of the poor.

For instance, he got 60,000 pucca houses built for the poor in 600 blocks of undivided Bihar within two years under the Indira Awas Yojna. By 1996, his government had 3,00,000 liveable houses built for the poor, according to data available with the rural development department.

He simultaneously focussed on the urban poor. He got multi-storied apartments built for them in high-end city localities. The buildings —named Bhola Paswan Sashtri Bhavan — were inhabited by those who had been homeless for generations. The buildings were built in the posh areas of Raja Bazar, Sheikhpura, Lohanipur, Rajendra Nagar and Kankerbagh in Patna and still stand testimony to how zealously Lalu had worked to ensure a better life and dignity for the poor.

In the process, he annoyed the powerful rural and urban elite who felt that “civilised people” were being forced to mingle with the “uncivilised”.

Beginning at Pusa in north Bihar, Lalu built 150 charwaha (grazer) schools across the state to enable poor children — who couldn’t have afforded to leave their farm chores to study — to read while tending to their cattle.

He raised the daily minimum wage for agriculture labourers from Rs 16.50 to Rs 21.50. Only Bengal paid a higher rate at that time. Lalu waived tax and cess on extracting toddy, providing a big relief to the then impoverished toddy tapping community that had over five lakh members in Bihar then.

While drawing a parallel between “Lalu’s 15 years and Nitish’s 15 years” at the Tuesday Talk and Mangal Shiksha Samvad on Tuesday, RCP quoted Napoleon Bonaparte — “a leader is leader in hope” — and equated Nitish with the French statesman and military leader.

RCP, while describing Lalu’s reign as a “blot” in the history of Bihar, gave a list of what Nitish had done in the past 15 years.

Over to RCP: “Find out what was the budget for education from 1990 to 2005. Nitish didn’t work only for the education sector but he also rescued Bihar from hell.

“Under Nitish’s 15 years of stewardship, the state has got two central universities, 20 medical colleges, three state universities, polytechnic and engineering colleges in most districts, an IIT and an NIFT among many other institutions, apart from a network of roads, supply of electricity and several other infrastructure.”

It is hard to compare Nitish with Napoleon. But to be fair to Nitish, what RCP said about educational institutions, roads, electricity and many other social contributions is true.

The condition of roads had been bad and the health and education infrastructure had crumbled when Nitish took over as chief minister from Rabri in November 2005. He paid attention to basic education, reviving and rebuilding school buildings in over 8,000 panchayats, laying rural and urban roads and augmenting electricity.

‘Wrong parallel’

“It is thoroughly unfair to describe Lalu’s regime as a reign of anarchy or ‘jungle raj’ and Nitish’s reign as susashan. Lalu and Nitish operated in two different eras and both had different challenges,” said Bihar’s senior-most socialist leader, Shivanand Tiwary, who has worked in close proximity with both Lalu and Nitish and is known for speaking his mind.

Currently, he is national vice-president of the RJD but minces no words when it comes to questioning Lalu. Shivanand had done the same with Nitish when he was with the JDU, earning Nitish’s wrath.

But then Shivanand’s analysis appears reasonable in the given context. Bihar had been a saga of over 75 per cent backwards and Dalits living on the margins of the political, social and economic power structure, with a handful of rural and urban elite monopolising the system.

Over 80 per cent children among the rural poor did not go to school and were treated as “un-teachable” by vested interests. Lalu, who arguably had inherited a viciously unequal society from the Congress in 1990, was the first leader who genuinely oriented his work to improve the life of the poor and the marginalised.

The Nitish government’s argument that Lalu didn’t allocate enough funds for education is incorrect. Lalu became chief minister at a time India was still mired in a pre-free market socialist economy. The size of Bihar’s budget was smaller than almost all other states in north India.

For instance, in the 90s the total revenue earning of Bihar, which included royalty on coal and central assistance, was around Rs 2,500 crore. Private investment and the corporate sector were struggling in the “licence-permit” era and the general business atmosphere was bleak.

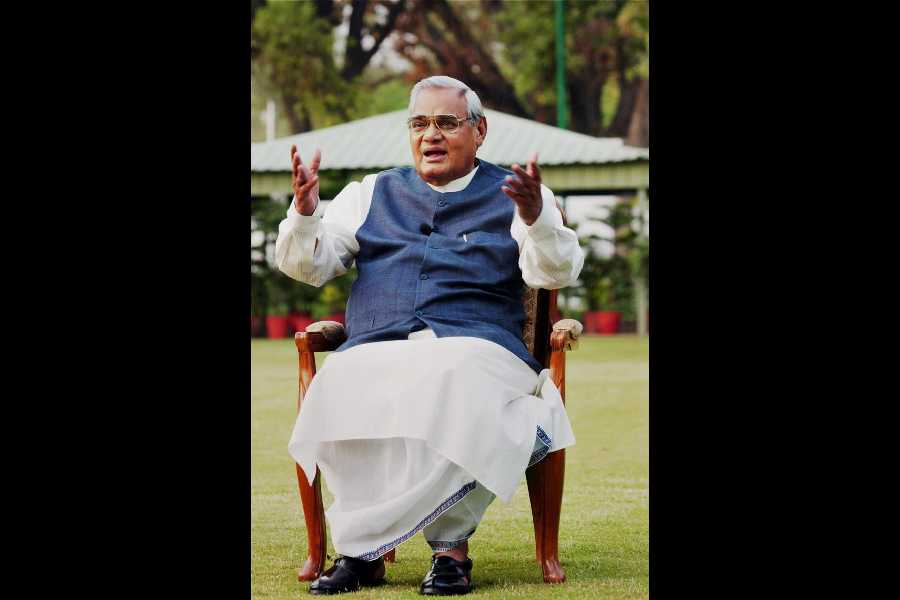

Nitish Kumar File picture

Scams and scandals

The regimes of both Lalu and Nitish have witnessed scams after their respective first tenures. While the fodder scam, called a “fraudulent drawl from the treasuries” by the CBI, witnessed the embezzlement of Rs 950 crore, the Srijan scam during Nitish’s tenure involved the siphoning of Rs 2,000 crore from the Bhagalpur treasury by the NGO Srijan Mahila Vikas Samiti, which was involved in giving vocational training to women and selling pickles.

While the fodder scam involved withdrawal from the district treasuries against fake bills, in the Srijan case, it was direct transfer of public funds to a private account, as per the FIRs.

The CBI began investigating the fodder scam in 1996. The same agency has been investigating the Srijan case since August 2017.

Lalu Prasad and many other political and administrative executives stand convicted in fodder cases and are behind bars. The CBI is yet to lay its hands on a major political executive in the Srijan case but people are wondering how a little-known NGO operating at a local level in Bhagalpur could have received Rs 2, 000 crore in its account without the knowledge or involvement of ruling politicians and senior bureaucrats.

Reward for good work

The electorate rewarded both Lalu and Nitish in almost equal measure for their good work. Lalu secured a massive victory for his party in the 1995 elections, sweeping the polls in united Bihar and winning 167 seats in the 324-member Assembly.

After 1995, Lalu got caught up in the politics of survival with fodder cases pursuing him. He landed in jail and demitted office in favour of his wife Rabri, and in the process losing control of administrative affairs.

Nitish too tasted massive victory in 2010; his JDU alone won 118 seats in the 243-member Assembly.

After 2010, Nitish has played political musical chairs, dumping the BJP to join the RJD-Congress Grand Alliance and then going back to the BJP against the backdrop of the Srijan scam.