A new labour law’s provision for a database of inter-state migrant workers has been ignored in the rules drafted to implement it, prompting questions about the government’s commitment towards some of the worst sufferers of the lockdown.

While the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, passed by Parliament in September, endorses the existing upper limit of eight hours’ work a day, the draft rules have controversially increased the possible spread-over time from the current 10-and-a-half hours to 12 hours.

The government has sought comments from the public over the next 45 days before the rules are finalised.

Section 21 of the Code says: “The central government and the state governments shall maintain the database or record, for inter-state migrant workers, electronically or otherwise in such portal... provided an inter-state migrant worker may register himself as an inter-state migrant worker on such portal on the basis of self-declaration and Aadhaar.”

But the draft rules unveiled by the labour ministry on Thursday mention no such database.

A 1979 law that is among 13 labour laws that the Code seeks to subsume had made it mandatory for labour contractors to register with the labour department all the migrant workers they take outside their state.

But the state labour departments never implemented the Inter State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) Act, 1979 — and the consequences of the neglect were seen after the lockdown began from March 25 this year.

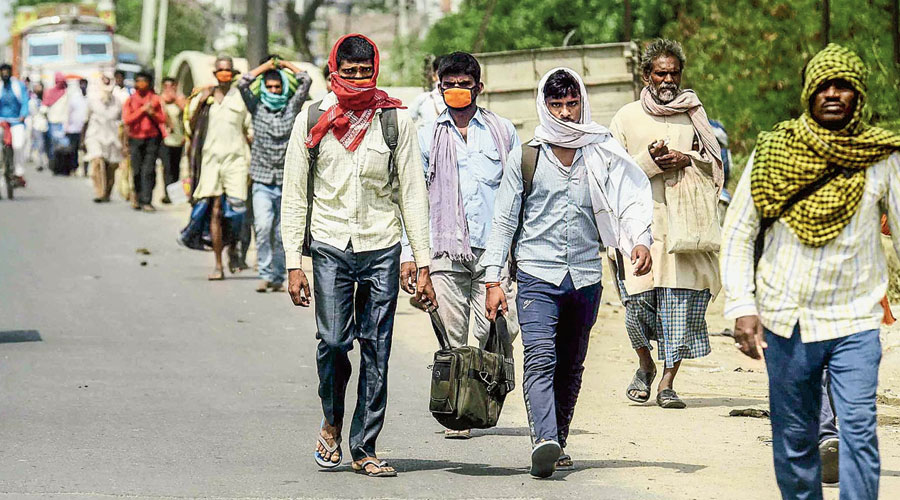

The lockdown left migrant workers stranded without jobs, money or transport, with most of the labour contractors having fled without paying them their dues and virtually all modes of travel suspended.

After near-starvation for days or weeks, millions of the workers chose to walk the hundreds of kilometres to their homes, many dying on the way. Some others bicycled, or hitched rides on trucks and buses paying exorbitant rates. When special trains began running, some of them were able to beat the rush and buy tickets.

Independent researchers have counted the deaths of 972 migrant workers from lockdown-related causes.

One reason the Centre and the state governments failed to do more for the stranded migrants was that they had no data on how many of them were living and working in which state, and at exactly which worksite.

Had the 1979 law been implemented, the governments would have had this data on the workers as well as on the labour contractors who had hired them.

The first version of the Code, introduced in Parliament last year, was silent on the registration of migrant workers. The government inserted the provision for the database after facing criticism.

Labour economist K. Shyam Sundar, professor of human resource management at XLRI, Xavier School of Management, Jamshedpur, said the database was unlikely to be created without the rules covering the provision.

He said the government seemed to have introduced the database provision as “a crisis-tackling measure”, to ward off criticism. “The rules do not specify how this can be implemented,” Sundar said.

The draft rules provide for a journey allowance for employees who have worked for 180 days in the last 12 months. It’s a once-a-year payment by the employer covering the worker’s travel home and back, and is expected to benefit migrant workers the most.

Sundar, however, said this provision could force a worker to stick to the original employer and forgo new opportunities.

The draft rules mandate annual medical check-ups for workers aged 45 or above. Sundar said this would exclude a sizeable proportion of workers.

Former labour welfare commissioner G.P. Bhatia said that young factory employees engaged in hazardous work were likelier to develop health problems. Medical check-ups should be provided to all the workers, he said.

The draft rules mandate safety committees and safety officers at establishments employing more than 500 workers in non-hazardous work, and at those employing over 250 workers in hazardous work.

All factories engaged in hazardous processes now need to have safety officers. The new provision too would exempt most production units from having to appoint safety committees or safety officers.

Work hours

The increased spread-over time of 12 hours, compared with the 10-and-a-half hours mandated in the Factories Act, 1948, has sparked controversy.

Bhatia supported the measure, arguing that workers in the eastern and southern states would benefit from four hours of rest during the hot afternoons.

Sundar, however, said factories might misuse the provision and force workers to work longer hours without overtime pay.

Workers who don’t live near their factory will have to spend the entire four-hour recess at the workplace, which would make them vulnerable to pressure to do extra work, he said. And 12 hours at the factory plus the travel time to and from home will severely restrict their family time and social lives.

“The employers will be incentivised to keep the workers on the worksite for the entire period. But one doesn’t know what the workers will be expected to do during the extra (period),” Sundar said.

“If the employers keep the workers (at the site) for the full 12 hours, and if we include travel time which in the metros would easily be another 60 minutes, then the workers’ work-life balance will be adversely affected.”

The draft rules say that no worker shall work more than five hours before having had a break of at least half an hour, a PTI report said.

The working hours in a day can be modified subject to the weekly cap of 48 hours, a flexibility provided also by the Factory Act.

According to the draft rules, while calculating overtime on any day, any period between 15 and 30 minutes will be counted as 30 minutes, PTI said. At present, any period of less than 30 minutes does not count as overtime, it added.