Taliban insurgents celebrating the takeover of her hometown in Afghanistan raped her sister, forced her family out of their home because of their ethnicity and turned it into a military camp. She says she is wanted by the Taliban for writing in a US journal and her plea for visa renewal in India has been rejected.

“I can’t apply for a job in India without a work visa and I can’t apply for a work visa here without a job,” the 23-year-old Delhi University pass-out told The Telegraph here.

With Afghanistan in turmoil and her facing the prospect of becoming one of the many stateless people, shorn of basic human identity and never quite accepted in their adopted country, the woman broke down while narrating her plight to this correspondent.

The young woman, who has recently completed her post-graduation in political science from Delhi University, was unwilling to be named or photographed.

She said her family had not spoken about the brutality on her younger sister because of threats from the Taliban. The militants took over her hometown, near the Turkmenistan border, on July 26.

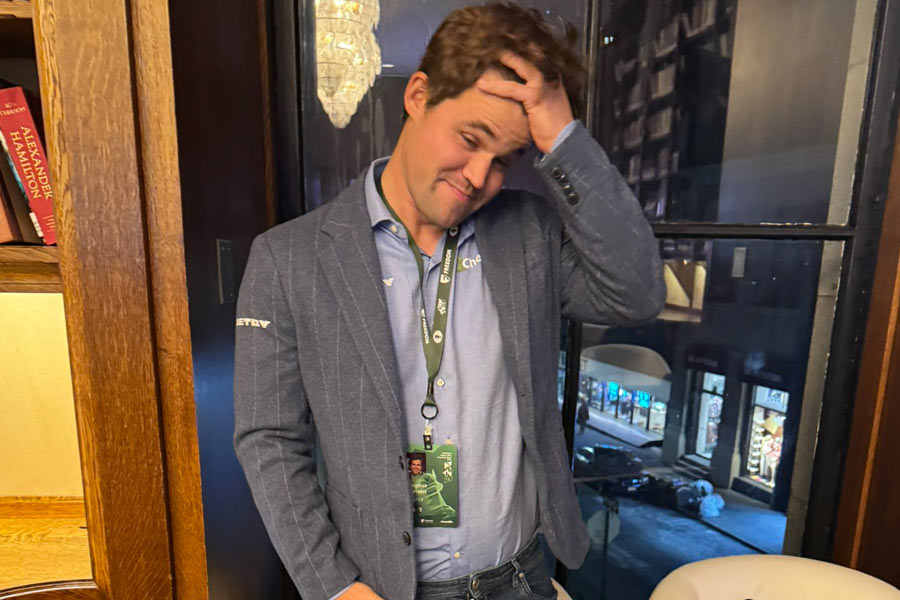

Jamshed Faizi at his Afghan naan stall in Kasturba Niketan Complex in New Delhi on September 7. The Telegraph

“My family decided not to make it public as it is an issue of honour, and they (the Taliban) threatened to kill them if they spoke to anyone about this. The Taliban members who have occupied our town are Pashtun, and we are Uzbeks who they do not consider true Muslims,” the woman said.

“My family members have all run away to different places and are in hiding. My sister, who was to join a course in Kabul University, is having a tough time and won’t be joining this semester. I am still traumatised and have told this only to very few close friends.”

The woman’s request for visa renewal in India has been turned down on the ground that she has completed her course of study.

“We are a secular Muslim family. Just because I wrote for a US military journal, the Taliban have issued a letter against me. Our home is now a military camp for them. As soon as they took over my hometown near Turkmenistan, they started marrying women forcibly and recruiting young boys. A friend of my brother who is in school turned up at the mosque one day with a big gun after being drafted (by the Taliban). My brother, who is 12 years old, was too scared to go to the mosque after that,” she said.

The woman has been issued an Asylum Seeker Card by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and her hearing is scheduled for December next year. She receives no institutional assistance and is surviving on remittances from an elder brother in Russia.

She wishes to emigrate to the US but has not received the documentation to prove her employment with the journal that she says she has been writing for.

“My flat here was recently burgled and my phone and laptop were stolen. Police have done nothing to solve the crime…. I have been here since I was 17. I go to gurdwaras and my favourite music that I play on my phone is kirtan. But without a visa I shall always be an outsider,” she said.

This newspaper spoke to several refugees in the Afghan quarters of Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar on Tuesday, hours after the Taliban had brutally suppressed a women’s protest for their rights on the streets of Kabul. Asked about the violence in Kabul, a woman vehemently refused comment, saying: “Taliban goli maar dega (The Taliban will shoot us).”

She was one among several young Afghan women — fashionably dressed and without headscarves — at the bustling Lajpat Nagar market in New Delhi.

In Delhi’s Afghan pocket of Lajpat Nagar, dotted with travel agencies, forex dealers and restaurants serving Central Asian food, incomes have been halved as the flow of medical tourists and students from Afghanistan has stopped after the Taliban takeover, as have international flights from that country’s main airports.

Most refugees here — usually forthcoming and hospitable to the media — declined comment when this newspaper visited Lajpat Nagar, reflecting the deep insecurity they felt for their loved ones back home.

Jamshed Faizi’s father had sent him to Delhi from their village near Mazar-i-Sharif three years ago to prevent him from being forcibly recruited by the Taliban. “The cities have fallen to them only now but they have been harassing us in the village for many years. My father said, ‘Just leave, do anything but get out of here. Our lives are over but you have your whole life ahead of you,’” he recalled.

Faizi, 21, is an expert naanwai who bakes Afghan naan breads like Paraki, Lavasa, Roghani, Roht, Bolani, Obi, Uzbeki and Afghani in a spherical earthen oven in a hole in the wall at the Kasturba Niketan Complex in Lajpat Nagar, where several Afghans live.

“Our daily sales are down from Rs 10,000 to Rs 5,000. Families that are here for medical treatment used to spend at least Rs 500 a day, but now they somehow make do with Rs 200 to 300 as the Afghan banks have stopped working and there are no remittances,” Faizi said.

“Even Indians don’t have enough work, so as a refugee I can’t expect to be allowed to work in the formal sector. What hurts is the extortion. Most landlords charge us double the normal rent. We pay for electricity at a flat rate of Rs 10 per unit to landlords who get it free (waiver for low consumption). But many Indians are very kind to us, like my Sardarji landlord,” he told this newspaper.

His landlord stopped on his way back from work to ask if Faizi had read the day’s newspaper. “It’s all bad news,” he replied. “It’s better to die hungry here than live as a slave under the rule of Pakistan and its henchmen.”

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has registered 15,217 Afghan refugees in India. Hundreds more have come over the past month. Refugee groups estimate the total number to be more than 21,000 now.

Many are camping outside the UNHCR office as well as the embassies of Australia, Canada and European countries. Faizi had participated in a protest outside the UNHCR office in Delhi for asylum and financial assistance, but got neither.

Another naanwai, 20-year-old Naseebullah Khan from Kandahar, came to Delhi five years ago to study at an Industrial Training Institute. He now survives on sales to Somali, Iraqi, Tajik and Uzbek medical tourists.

“I wish I could work on the things I learnt at the ITI. But I can’t return to Kandahar. What you see on TV in Kabul is jannat (heaven) compared to the jahannum (hell) in my hometown,” he said.

Rohid Afzali from Kabul and Nadeem Obaidi from Mazar-i-Sharif have family in Canada and want to join them there. They have been staying in the Kasturba Niketan Complex for a couple of years, trying for a visa.

“We feel bad and helpless for what is happening back home. Women can’t study, those of us who have studied can’t find jobs. We came here as it is believed that emigration is easier from India, and it was too unsafe back home. Little did we know that our countrymen in Delhi have been struggling here for decades,” Obaidi said.

Afzali weighed in: “My political science degree is of no use. A travel agency we ran back home has shut, and here too Afghan restaurants have been hit since the pandemic begun. I’m stuck, there’s nowhere to go and I’m totally dependent on funds from relatives in Canada. For how long, I don’t know.”