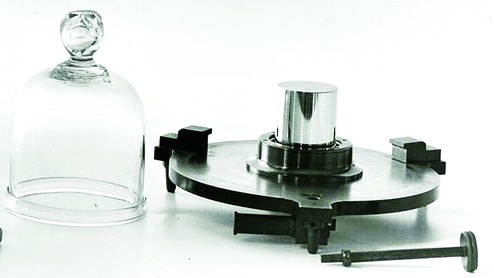

July 26: Beneath a hill overlooking Paris, there is a vault. On the door of the vault there is a lock requiring three keys, only two of which are kept in France. Inside you will find the most important lump of metal in the world: the kilogram.

Soon it will just be "a" kilogram. The platinum-iridium cylinder that for 125 years has defined the mass of everything is to be retired. When it does, the half century-long modernisation of the world's measurements system will at last be completed but the basis of those measurements will also, for most people, be harder to understand.

Rather than being linked to a lump of metal, the weight of everyone and everything on the planet will be linked to a number, the Planck constant.

There was a time when the kilogram was not the only object of this kind. There was also the metre, a length of metal kept in a climate controlled-vault.

But it was redefined in 1983 as the distance travelled by light in a vacuum in 1/299,792,458 of a second, and that physical metre became a museum piece.

The second, by then, had been redefined. Once an 86,400th of an average day, today it is defined using the caesium atom. The advantage was that rather than relying on an object, whether a rod of metal or the Earth itself, both units could be described to a scientist on the other side of the world, or even an alien, and understood. More important, they could never change.

The kilogram, though, has held out. Stuart Davidson, of the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), in southwest London, looks after the UK mass scale, helping disseminate the correct mass to Britain's scientists.

"Because the kilogram is an artefact, we know it is not perfectly stable," he said.

"We know it is changing weight because a set of identical copies were also made and they have now diverged.

"The difference is tiny, a hundredth the weight of an ant, but sometimes that matters. The new definition uses an apparatus known as a Kibble balance, which offsets a weight against an electromagnet. In this way, it can relate mass to a fundamental constant of quantum physics, Planck's constant.

The official kilogram will leave service in spring 2019. The NPL is developing commercial Kibble balances so that laboratories can use Planck's constant rather than a lump of Parisian metal.

As far as Davidson is concerned, it is not before time. "While it's nice to be able to point at an artefact and say, 'That's a kilogram', it also makes it look like the mass community is in the 19th century. If you go back 4,000 years, this would be a recognisable technology. So this brings it up to date by using something with lasers and flashing lights."

THE TIMES, LONDON