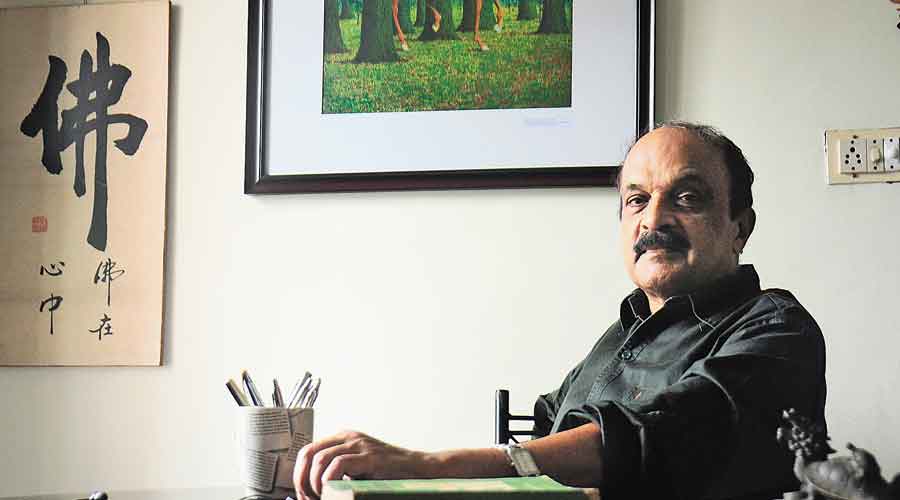

Indian democracy is feudal, ruthless and despotic, says Kerala writer Paul Zacharia, chosen earlier this month for the state’s highest literary award, the Ezhuthachchan Puraskaram, in an interview with Nazeem Beegum.

You were so hopeful about the country turning around from the present political situation before the Bihar election results were declared. Do you think the communal agenda is gaining momentum again?

People are voting communally everywhere, not just in Bihar. Every party is using the communal card to create a vote bank, not just the BJP. The parties openly say it without any shame. The problem of communalism comes up when you try to turn your communal attitudes against another community to eliminate or isolate or suppress it.

India has not been secularised — there exists the entire problem. We are still steeped in blind faith and it is exploited by political parties. We have not progressed like Europe, which progressed after the Industrial Revolution, Enlightenment, scientific revolution and the demolition of Christianity.

Europe progressed only after Christianity was deconstructed. Religion ceased to be a force in European society. That was the moment of awakening and progress for the entire western culture because people started thinking freely. In India, that never happened.

So, if you ask me about the Bihar elections, all played these cards very well there, and the BJP has proved that it is smarter than other parties.

Do you think Indian voters are mixing their religious faith with political beliefs?

Many voters in states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh or any such state are illiterate. Unlike (voters) in Kerala or even Tamil Nadu, they have received no modern education. They might be able to read and write but beyond that they have not been able to look at the world with new eyes and an understanding of what is happening.

First of all, there is a feudal set-up where the village pradhan commands for whom they should vote. Second, they are not able to differentiate between communal parties and others. This political illiteracy and lack of education makes millions incapable of distinguishing between the communal appeal and the political appeal. Our communal parties are experts in confusing and mixing up the two, and cheating the people.

Kerala is going to face crucial local body elections next month. Do you think these elements will play a role there?

Yes, because at the micro level, communal passions are stronger and can be exploited better than at the Assembly and parliamentary levels. But in Kerala, people are different from other states as they have received a certain amount of education and have a general awareness of what is going on. People are a little more demanding, and know their community needs and what they want to improve their lives.

Besides, the Left still has a very strong hold on Kerala. The Left has a hold across all communities — Hindus, Muslims and Christians. That is a very important factor.

There is a growing nationalistic fervour in north India that favours the BJP. But it is not happening elsewhere. How do you explain this?

That again is (a result of) illiteracy. These superfluous emotions are exploited where people are illiterate. Therefore, when somebody talks about nationalism in Kerala, Malayalis know they are as nationalist as anybody else…. Hindi is a blanket language covering several cultures, and so the identities are always mixed up. This is one reason that such foolish and ridiculous ideas are being sold easily to populations who have no identity to claim.

Moreover, Hindi as a language has been misappropriated by those who hold power. Those looking for larger power use the language used by the majority.

Could you tell us about your Delhi days?

I was there for 20-22 years. I went (there) as a greenhorn fellow from the south and I had, frankly, O.V. Vijayan (author and cartoonist) to help me learn about Delhi. Through Vijayan, V.K. Madhavan Kutty (journalist) and people like them, I came to understand how the Indian power system works, how Indian politics works, and what kind of agendas are taken at the end of the day, what kind of puny little people have power in India and how they take India for a ride.

I learned the fundamental thing: how democracy is also taken for a ride by people with money, muscle power and all kinds of agendas, like the communal agenda.

The basic thing I learned in Delhi is that democracy is only a mask and just a catchword, and that Indian power is always feudal, despotic and ruthless. I never had any occasion to change that viewpoint. So when I see Modi & Co. acting in a particular way, I’m not surprised.

Whenever the nation travelled in the wrong direction in the past, the voices of intellectuals were heard from Delhi. Why isn’t that happening now?

When you talk about the Nehruvian and Indira Gandhi days, yes, intellectual voices did rise. That generation is dead. The question of intellectuals and individual voices having an impact on governance is almost nil. After Independence, those things evaporated, mostly through political interference and suppression.

The initiative was lost, and so you cannot look to Delhi or any other particular place in India for that. Intellectually eminent people are there, but scattered all over India.

You are no longer a pariah for the Leftists, who assaulted you physically in 2010. Do you see a change in their attitude? You have won the government’s highest literary award too.

That was done by some idiots at the local level of the (CPM youth wing) Democratic Youth Federation of India. I call them “pozhans” or stupid idiots. I didn’t care even then. But it was terrible (that) the people who did that were promoted. The very sad part was that the party justified that. I think V.S. Achuthanandan was the chief minister then. He, or the party, did not condemn the incident and one of its leaders justified it. It happened almost a decade ago.

Maybe the party is changing slowly — I don’t know. But if the party still continues to be so, it’s not a problem for me or you. The party has to handle it.

Speaking about the award, of course, it is an award constituted by the government, which is elected by the people. So I see it as an award from the people, not any institution.

Nazeem Beegum is an independent journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala