Here is a little glimpse into the man we describe by that disliked anonymous noun called The Enemy: Captain Imtiaz Malik of the Pakistan Army’s 165th Mortar Regiment.

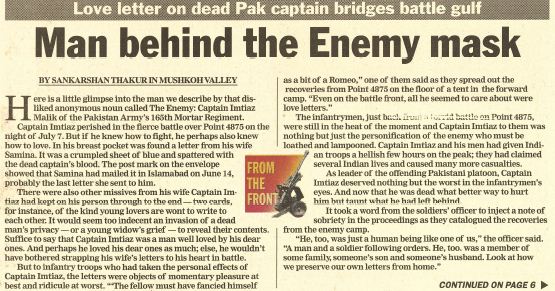

Captain Imtiaz perished in the fierce battle over Point 4875 on the night of July 7. But if he knew how to fight, he perhaps also knew how to love. In his breast pocket was found a letter from his wife, Samina. It was a crumpled sheet of blue and spattered with the dead captain’s blood. The post mark on the envelope showed that Samina had mailed it in Islamabad on June 14, probably the last letter she sent to him.

There were also other missives from his wife Captain Imtiaz had kept on his person through to the end — two cards, for instance, of the kind young lovers are wont to write to each other. It would seem too indecent an invasion of a dead man’s privacy — or a young widow’s grief — to reveal their contents. Suffice to say that Captain Imtiaz was a man well loved by his dear ones. And perhaps he loved his dear ones as much; else, he wouldn’t have bothered strapping his wife’s letters to his heart in battle.

But to infantry troops who had taken the personal effects of Captain Imtiaz, the letters were objects of momentary pleasure at best and ridicule at worst. “The fellow must have fancied himself as a bit of a Romeo,” one of them said as they spread out the recoveries from Point 4875 on the floor of a tent in the forward camp. “Even on the battlefront, all he seemed to care about were love letters.”

The infantrymen, just back from a torrid battle on Point 4875, were still in the heat of the moment and Captain Imtiaz to them was nothing but just the personification of the enemy who must be loathed and lampooned. Captain Imtiaz and his men had given Indian troops a hellish few hours on the peak; they had claimed several Indian lives and caused many more casualties.

As leader of the offending Pakistani platoon, Captain Imtiaz deserved nothing but the worst in the infantrymen’s eyes. And now that he was dead what better way to hurt him but taunt what he had left behind.

It took a word from the soldiers’ officer to inject a note of sobriety in the proceedings as they catalogued the recoveries from the enemy camp.

“He, too, was just a human being like one of us,” the officer said. “A man and a soldier following orders. He, too, was a member of some family, someone’s son and someone’s husband. Look at how we preserve our own letters from home.”

In his hand the officer held a letter to Captain Imtiaz from a senior in the Pakistani Army commending him for selection to a specialised artillery course. It was full of praise for the young captain and its tone, typically, was utterly patronising. “Their senior officers write to their juniors just like ours do,” remarked a soldier on hearing the letter’s contents, and the tent rippled with a round of well-meant laughter.

Captain Imtiaz, if only for a moment, had become just another soldier doing his duty and rising up the ranks in just another army. “I got a similar letter from my instructor when I passed out of artillery school,” said one soldier, sounding suddenly piquant and even a little affectionate.

By now the tent floor was a mosaic of the debris of a destroyed Pakistani bunker — probably the most engaging exhibition so far of the depth of Pakistani involvement in the invasion of upper Kashmir. Among the stuff the Indian soldiers had brought back from Point 4875 were two long-range Pakistan Army field transmitters, a dozen-odd Operation Cards (identity cards) of Pakistani soldiers, rank and unit labels of the Northern Light Infantry, the main Pakistani regiment involved in the incursion, gas masks and chemical weapons filters, a roll of Konika colour film, ration supply registers for forward units and an album full of photographs of soldiers with each other and with their families.

But, perhaps, the key recovery was a file in which were notings of the minutest details of Indian artillery and infantry positions in the Drass sector.

“Thank god our gun positions have now been shuffled about,” said one officer, aghast at the sharp detail the Pakistanis had in their possession. “I used to wonder why their fire was coming so close to us, but now we know.”

Among what was obviously a treasure for Indian troops was also Captain Imitiaz’s bank passbook and a wad of cheques he had had no opportunity to use. In the event he went away signing an overdraft on his life.

This story was first published in The Telegraph in 1999