Kalighat pat paintings are among some of the most eye-catching Indian art sold online. But at Kalighat Patuapara, the place of their origin, you don’t get them any more.

Among the 70 families of Patuas who live there, there is barely anyone who makes pats now. Only one person, Bhaskar Chitrakar, is identified as a pat artist. The rest of the patua community at Kalighat has switched to idol-making, though Chitrakar, which means painter, remains their chosen surname.

With only a few days to go for Durga Puja, the lane in which the families live and work has turned into a line-up of idols.

This is their busiest season and the idol-makers do not have time for useless talk — and a question about pat paintings falls into that category.

Bhaskar is not exactly enthusiastic about an interview, either. He is visiting the frenetic studio of his brother Bishwajit Chitrakar, where several idols are being made. Bhaskar is not keen to bring out his works into the studio. “Too many people want to see his work, but few buy them,” says Bishwajit.

Earning a living as a pat painter is tough, though the paintings continue to grace the walls of elegant drawing rooms.

Most of the pat paintings that are being made now, by Bhaskar and others, are an attempt to update the original art, in content, style and price, so as not to seem entirely anachronistic.

Kalighat pats began to evolve around Kalighat’s Kali Temple after its present structure was built in 1809. Artists from south Bengal settled near the temple and began to make the pats for pilgrims to pick up as cheap temple souvenirs. Many families in Patuapara are from Midnapore.

The pats that are now made as decoration or art are not cheap.

The early painters churned out the pats fast with quick brush strokes, which gave them their distinctive style, says R.P. Gupta, in his essay Art in Old Calcutta: Indian Style published in the first volume of Calcutta The Living City. He writes about how the paintings required only a single sweep of the brush. This resulted in the “firm and flowing boldness of line”. Gupta observes that the Kalighat patuas turned “the need for speed into a superb inner spontaneity”.

The pats were both religious and secular. Gods and goddesses abounded, as did mortals who became iconic — the Babu and the Bibi, the man turned into a docile sheep by his mistress and the hypocrite cat-hermit who eats fish on the sly. The voluptuous, rounded figures betrayed no fear of flesh and the boldness of the lines captured the boldness of the gaze, especially of the women.

The exaggerated portrayals mocked the vanities and the illicit excesses of 19th century Calcutta lifestyle with a delicious wickedness. They were brilliant social satire, Gupta stresses their parallel existence with the popular street publications of Calcutta, also known as Battala literature. But the pats also robustly celebrated a way of life.

The rise of photography killed pats, long ago. So in a way it is surprising that pats exist at all.

Their survival proves the strong appeal of the original art form.

Compared to the Babu-Bibis of yore, Bhaskar’s men and women seem strictly on a diet. The brush strokes have also lost their sweep. The colours are far more solid. And the subjects are not so much a satire of social mores as an acknowledgement of the hybrid nature of our contemporary reality, depicted through retro art.

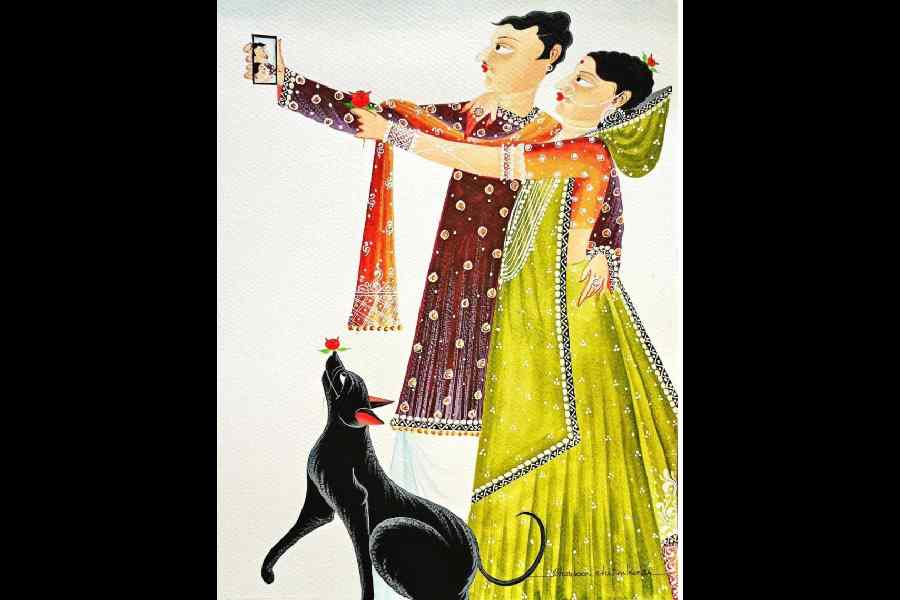

Bhaskar’s paintings show a slim Babu-Bibi pair in 19th century Bengali attire seated inside a green and yellow auto, or taking a selfie, as a dog balances a rose on the tip of its nose; the rose is a motif from earlier pats. “I made my figures thinner to keep up with the times,” says Bhaskar. “I think up new themes,” he adds.

Pat paintings

He has painted the Kahlo-Kali figure which combines the figures of the Mexican painter and Kali, the goddess. Kahlo-Kali is a visual pun and a literal one in Bengali.

As Gupta points out, the original pats had also absorbed western influence in the choice of watercolour and in the shift to paper from cloth.

Bhaskar’s paintings are available online. “Perhaps one day I will also turn to idol-making,” he says. “But not yet.”

Not that idol-making is an easy career either.

Bhaskar’s elder brother, idol-maker Bapi Pal, who also identifies as Indrajit Chitrakar, says that the community faces immense financial hardship. “The total number of people working in idol-making here in Kalighat goes up to a few thousands. To keep things going studio owners have to take huge loans,” he says.

“We appeal to our chief minister Mamata Banerjee, who lives right here and sees us, to help us,” he says. “If she can give a grant of Rs 85,000 to every Puja organiser, why can’t she give a grant to us, who make the idols?”

An elderly idol-maker, who is not keen to share his name, agrees. “It is a very hard life,” he says. Pat-making also disappeared, he adds, because no one learned the skills.

But the pats live on in the idols, says Bishwajit “Our idols are distinctive, more rounded, mostly in ekchalas, different from Kumartuli idols. I think when our earlier generations turned to idol-making, they brought the features of the pats to the idols.”