The debate on the continuation or abrogation of Article 370, titled a “temporary” provision in the Indian Constitution, has been going on for decades but it was almost unthinkable that Jammu and Kashmir’s special status could be scrapped in this manner, without the concurrence of the Assembly.

While no political party except those belonging to Jammu and Kashmir — the National Conference and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) — ever adopted a rigid approach, there was consensus that the article symbolised the spirit of accommodation and should be continued despite its gradual ineffectiveness.

The government’s sudden decision is bound to hurt as the sense of alienation has increased in the past few years.

Jammu and Kashmir is the only state that had negotiated its terms of association with the Union of India and Maharaja Hari Singh had signed the Accession Treaty with India on October 26, 1947, under unique circumstances as it was not easy for a Muslim-majority state to take this decision. The state acceded to India only in respect to defence, foreign affairs and communications and the sacred commitment manifested itself in the form of Article 370.

Article 370 was finalised after protracted negotiations between Kashmir — led by Sheikh Abdullah — and Delhi from May to October in 1949.

Legal expert A.G. Noorani in his book on Article 370 writes on the basis of documents and negotiations of that time: “Neither side can amend or abrogate it unilaterally, except in accordance with the terms of that provision.”

That India conceded special status for Jammu and Kashmir was clear in the unanimous agreement to allow the state to have its own Constitution. Even the change of nomenclature — from Prime Minister to chief minister of the state — was done only on April 10, 1965, when Kashmir’s Constitution was amended by the Assembly. Even Indian constitutional amendments were applicable to the state only after the Assembly’s approval.

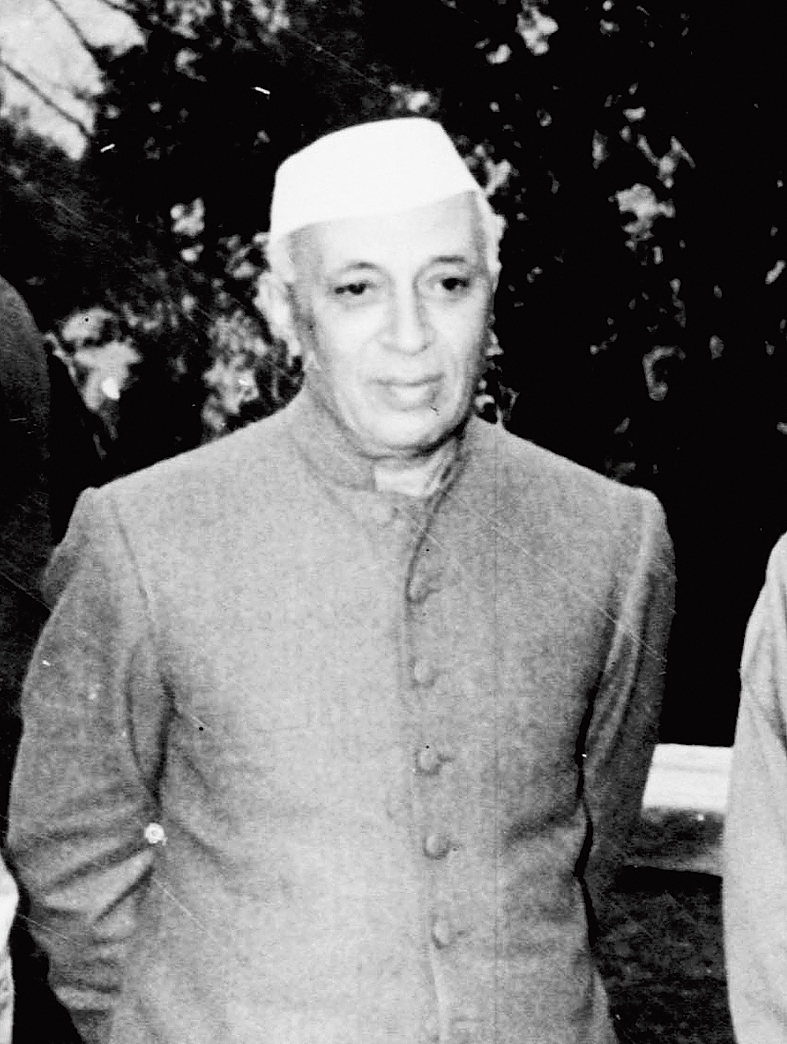

A reply in Parliament on November 27, 1963, by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to a question about any plan to repeal Article 370 gives the traditional perspective on the special provision.

Nehru had said: “Article 370 is part of certain transitional provisional arrangements. It is not a permanent part of the Constitution. It is a part as long as it remains so. As a matter of fact, it has been eroded, if I may use the word, and many things have been done in the last few years which have made the relationship of Kashmir with the Union of India very close.”

Nehru continued: “There is no doubt that Kashmir is fully integrated. The fact that there may be some special matters attached to it does not come in the way of integration at all, and I gave as an instance that in Kashmir citizens of India other than those of Kashmir are not allowed to buy land or own property. I think it is a very good rule which should continue, because Kashmir is such a delectable place that moneyed people will buy up all the land there to the misfortune of the people who live there.”

The then home minister, Gulzarilal Nanda, also once said in Parliament that only the shell of Article 370 was there as its contents had already been emptied out.

The central government used presidential orders to dilute the provision but most of the changes were made without any confrontation with the state. But sentiments changed in the Valley post-militancy in the early nineties and the situation came to such a pass that the National Front Government passed a resolution in the Assembly and submitted a memorandum on that basis to the Centre on November 5, 1995, asking for greater autonomy to the state.

That signalled a hurdle in the integration process, reflecting the sense of alienation among the people, which was largely caused by the misadventures of Congress governments at the Centre. The memorandum, apart from other things, asked the word “temporary” to be deleted from the Constitution in the heading of Article 370, to be substituted by the word “special”. This change in ground reality, which has worsened after remarkable normality during the Manmohan Singh regime for some years, heightened the symbolism of Article 370.

The Manmohan Singh government had formed a working group that examined various issues about the state, including the special status under Article 370. While the NC reiterated its demand for greater autonomy before this working group, the PDP — with whom the BJP had aligned to form its first government in the state — called for self-rule, triggering a major controversy.

While the BJP demanded abolition of the provision, the Congress said Article 370 should be treated as a permanent feature of the Constitution.

What that indicated was the reversal of the trend as the rigidity on Article 370 was intimately linked with the ground situation. The last few years have been miserable both in terms of violence and governance and currently there is no elected government either. At this stage, the abrupt decision of scrapping the state’s special status will indisputably be taken as a hostile gesture and only time will tell how this government manages the fallout.