India’s space agency continues its silence on the investigation into the malfunction that led to the loss of its moon lander shortly before touchdown earlier this month, although the lander’s 14-day window of intended operations closes by Saturday.

The Indian Space Research Organisation said on Thursday that a “national-level committee consisting of academicians and Isro experts are analysing the cause of communication loss” with the lander, Vikram, during its descent towards the lunar surface on September 6.

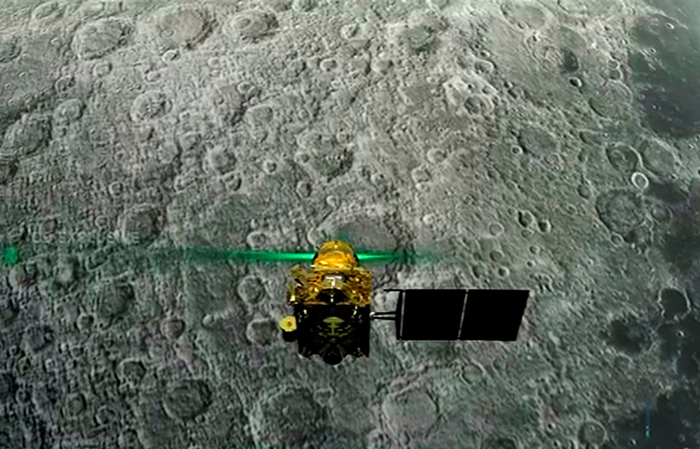

Vikram, a key component of India’s Chandrayaan-2 mission, had followed its planned descent trajectory to about 2.1km above the moon’s surface when something went wrong.

While Isro has not revealed data about Vikram’s speed or trajectory after the 2.1km point, scientists who used a radio telescope in the Netherlands to track the lander during its descent believe it crashed on the moon’s surface at a speed of about 180kmph.

“The lander is unlikely to have survived the crash --– imagine a car hitting a wall at 180 kilometres per hour,” Cees Bassa, a scientist at the Netherlands Institute of Radio Astronomy who was involved in the radio telescope observations, told The Telegraph.

An Isro spokesperson on Friday declined comment on the observations made through the Dutch radio telescope, asserting that a panel of technical experts was analysing data to understand the events.

A crash as indicated by the telescope’s observations would imply a malfunction during the lander’s “fine breaking phase”. During this stage, Vikram’s four rocket thrusters and other onboard orientation and stabilisation systems should have reduced its horizontal velocity to near zero and prepared it for a slow vertical descent from an altitude of 400 metres.

Senior aerospace engineers formerly associated with the space programme say the data from the radio telescope, along with the trajectory lines displayed by Isro during the descent, suggest the malfunction prevented the lander from slowing down and led to its crash.

The trajectory lines, taken together with the radio telescope data, raise the question what happened first: a malfunction or a loss of communication, said Roddam Narasimha, former director of the National Aerospace Laboratories, Bangalore, and former member of the space commission.

“If something went wrong during the breaking phase, the lander would have fallen with a thud,” he said. And a hard fall could itself have led to a loss of communication.

Many scientists, though, believe that the failed soft-landing should be no cause for embarrassment. “A lunar landing is hard; there is nothing disgraceful about this crash,” Bassa said.

Scientific instruments aboard the Vikram lander, which contained a robotic rover, were intended to relay data from a previously unexplored area near the lunar south pole. The lander was designed to function only during the 14-day period of lunar daylight.

The Chandrayaan-2 lunar orbiter, the second component of the mission that is equipped with cameras and other instruments for scientific observations, remains in orbit.

“All (the) payloads of (the) orbiter are powered. Initial trials for orbiter payloads are completed successfully,” Isro said on Thursday.