Scientists with the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) have generated the most detailed undersea map yet of Adam’s bridge, confirming the submerged ridge as a “continuity” from Dhanushkodi in India to Talaimannar in Sri Lanka.

The mapping exercise carried out with a US satellite that bounced laser beams off the sea floor has established that 99.98 per cent of the Adam’s bridge — a 29km chain of limestone shoals — is submerged in shallow waters.

The study “is the first to provide intricate details” about the submerged sections of Adam’s bridge, Giribabu Dandabathula, a scientist with Isro’s National Remote Sensing Centre in Jodhpur regional centre, and his collaborators said describing their findings in the journal Scientific Reports.

An East India Company cartographer had labelled the submerged structure Adam’s bridge. The structure is also known as Ram Setu and described in the epic Ramayana as a bridge built by the ape army of Ram to help him reach Sri Lanka, the land of Ravana, to win back his wife Sita.

Geological evidence suggests that the currently submerged ridge is a former land connection between India and Sri Lanka. Persian navigators in the 9th century AD had described the bridge as Sethu Bandhai, or a bridge over the sea. Temple records from Rameswaram suggest the bridge was above sea level until 1480 when it was destroyed during a cyclone.

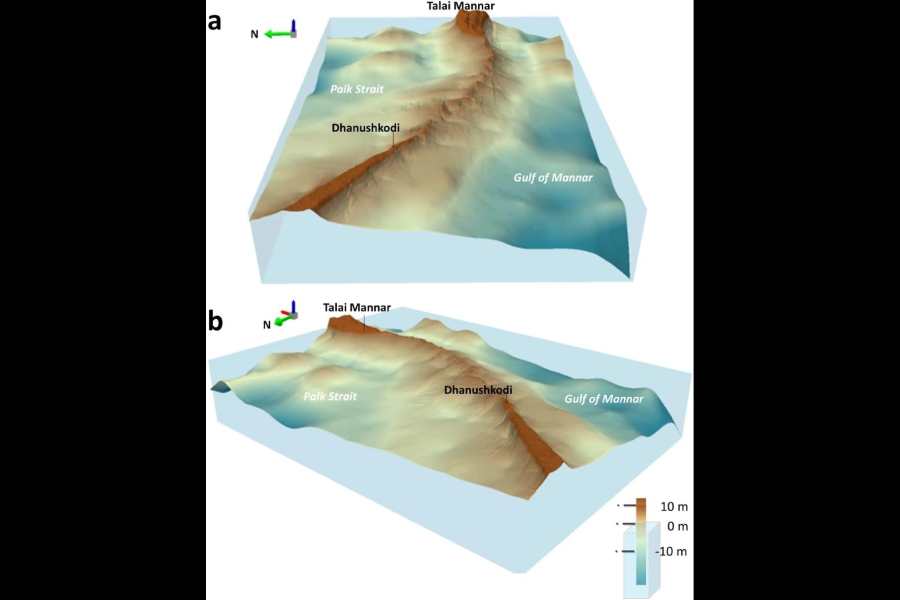

Detailed 3-D perspective views of the Adam's bridge as seen in Isro's novel 10m-resolution digital bathymetric data. (top) As seen from the Gulf of Mannar as an observer position; (below) as seen from the Palk Strait as an observer position

Earlier satellite-based observations had revealed the undersea structure but were largely focused on exposed sections of the bridge. The sea in the area is super shallow, only 1-metre to 10-metre deep in places that hindered navigation and any attempts to map the ridge with ships.

For their study, Dandabathula and his colleagues at the NRSA, Hyderabad, used the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Ice Cloud and Land Elevation (ICESat)-2 equipped with a laser-borne altimeter to look beneath the water.

The researchers used ICESat-2 data from October 2018 through October 2023 to create a 10-metre resolution map — or sharp enough to capture features the size of a train coach — of the entire length of the submerged ridge.

Their analysis has shown that the ridge along nearly its entire length is about 8 metres above the seabed. But only about 0.02 per cent of the volume is exposed or visible, the rest is submerged.

Limestone emerges from the fossils of marine organisms. As shells and skeletons of marine organisms build up on the ocean floor over millions of years, their layers push down on each other, turning into solid rock.

Their study has also revealed 11 narrow channels, only a few metres across, that allow water to flow, or to be exchanged between the Gulf of Mannar on the southwest side and the Palk Strait on the northeast side of the ridge.

The scientists believe that these narrow channels — or gaps along the axis of the ridge — likely play a key role in protecting or preserving the structure from the ferocity of wave action.

The bridge is continuously exposed to the energy from strong waves from both its sides — the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait.

The summer monsoon currents bring water from the Arabian Sea into the Bay of Bengal during the southwest monsoon, while the winter monsoon currents carry Bay of Bengal waters via the Palk Strait and Adam’s bridge into the Arabian Sea during the northeast monsoon.

The Isro team has said the narrow channels permit the free flow or exchange of water between the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait, helping reduce the impact of the waves on the ridge.

“This is a nice scientific paper that describes previously undocumented features of the submerged ridge,” said Mayank Vahia, former professor of astronomy at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, who was not associated with the Isro study. “It corroborates the natural, geological origins of the limestone structure.”

Both India and Sri Lanka were once part of an ancient supercontinent called Gondwanaland that separated and drifted northward as an isolated giant island landmass in the Tethys Sea until it crashed into the supercontinent called Laurasia sometime between 35 million and 55 million years ago.

Over millions of years, sea levels have risen and fallen, submerging and exposing the ridge, said Vahia who has independently been studying the history of astronomy and science in ancient civilisations.

The other study co-authors in the Isro paper are Prakash Chauhan, Sushil Kumar Srivastav, Apurba Kumar Bera, Anisha Poonia, Niyati Patidar, Aryan Sharma, Jayant Sharma, Rohit Hari and Koushik Ghosh.