The most detailed analysis of occupational patterns in a nation ever attempted could compel historians to revise textbooks and push back the start of industrialisation by over 100 years.

The analysis led by researchers at the University of Cambridge has found that Britain experienced a steep decline in counts of people engaged in the agricultural peasantry and an increase in those engaged in manufacturing during the 17th century.

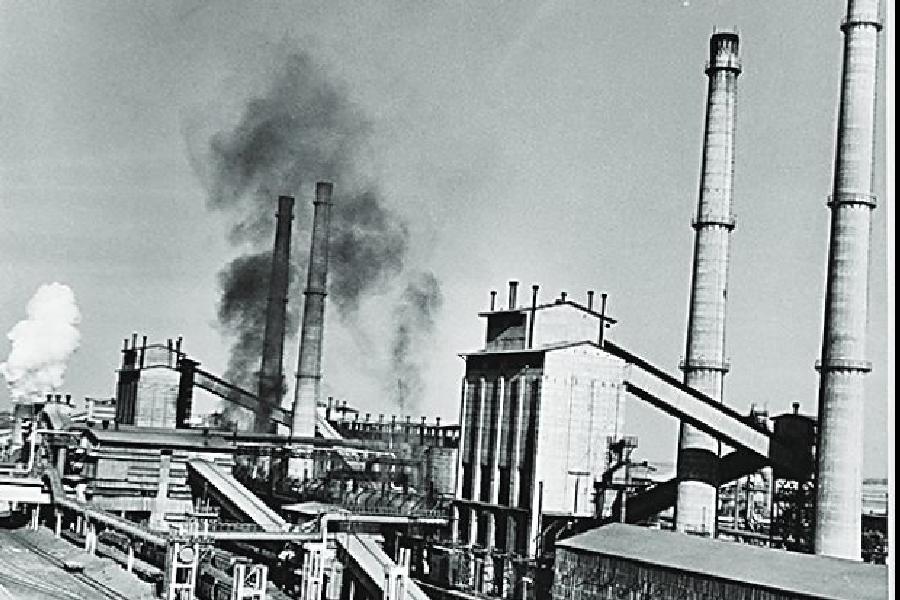

Blacksmiths, shoemakers, wheelwrights and weavers were among those who marked this transition from agriculture to production over a century before the emergence of mills and steam engines in the late 18th century that is widely viewed as the start of industrialisation and economic growth.

“A long period of industrialisation preceded the industrial revolution,” Leigh Shaw-Taylor, a professor of economic history at Cambridge who led the analysis, told The Telegraph. “The period from 1600 to 1700 and likely from 1500 to 1700 saw an increase in the labour force in industry and hence output too.”

Metalworking, shoemaking or weaving were for sure similar in the 16th or 17th century as they were in previous centuries. “What changed was the share of the labour force in industry,” said Shaw-Taylor who heads a research effort to probe occupational patterns in Britain from the 14th to 20th centuries.

The insights into early industrialisation emerged from over 160 million records — census data, parish registers, probate papers, among other documents — spanning over three centuries that showed how certain occupations grew over time.

While agriculture dominated occupations across much of Europe, Asia and elsewhere during the 16th and 17th centuries, the analysis has revealed a shift towards manufacturing goods in Britain. Estimates of male agricultural workers in Britain fell from 64 per cent in 1600 to 42 per cent in 1740. And the share of men engaged in goods production increased from 28 per cent in 1600 to 42 per cent in 1700.

The findings are set to be presented at the annual conference of the Economic History Society on April 6.

“We can’t say why this change occurred in Britain rather than elsewhere,” Shaw-Taylor said in a media release issued by the university. “However, the English economy of the time was more liberal with fewer tariffs or restrictions unlike elsewhere on the continent.”

Trade guilds could have also influenced policies in some countries, he said. Textile production, for instance, was prohibited in the countryside around the Dutch city of Leiden, while in Sweden, no shops were permitted in rural areas within a certain radius of a town until the

19th century.

The analysis has suggested that half of all manufacturing employment in England in 1700 was in the countryside. “Industries of textiles or metalworkers making nails or scythes were shaped like factories without machines spread out over hundreds of households — and produced goods for international markets,” Shaw-Taylor said.