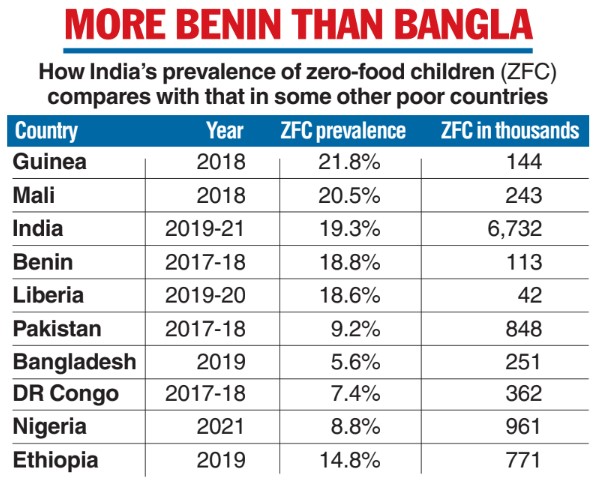

India’s prevalence of so-called “zero-food” children who have not eaten anything whatsoever over a 24-hour period, assessed through snapshot surveys, is comparable to the prevalence rates in the west African nations of Guinea, Benin, Liberia and Mali.

A study that used data from the Union health ministry’s national family health survey for 2019-2021 has estimated India’s prevalence of zero-food children at 19.3 per cent, the third highest after Guinea’s 21.8 per cent and Mali’s 20.5 per cent.

The figures are much lower in Bangladesh (5.6 per cent), Pakistan (9.2 per cent), DR Congo (7.4 per cent), Nigeria (8.8 per cent) and Ethiopia (14.8 per cent).

Health experts familiar with child nutrition issues in India say the deprivation of food leading to zero-food children is likely to reflect not a lack of access to food but the inability of many mothers to provide appropriate feeding care to their infants.

Zero-food children are infants or toddlers aged between six months and 24 months who have not received any milk or solid or semisolid food over a 24-hour period.

The researchers who conducted the study compared estimates of zero-food children across 92 low-income and middle-income countries.

Across the 92 countries, over 99 per cent of the zero-food children had been breastfed, indicating that almost all the children had received some calories even during the 24-hour period during which they had been deprived of food.

But at six months, breastfeeding is no longer sufficient to provide children with the nutrition they require. Children then need adequate protein, energy, vitamins and minerals through additional food along with breastfeeding.

The health surveys, conducted across the 92 countries at different times between 2010 and 2021, suggest that South Asia has the highest counts of zero-food children, an estimated 8 million, with India accounting for over 6.7 million.

“The numbers highlight… the urgent need for tailored interventions to address this issue,” population health researcher S.V. Subramanian from Harvard University and his colleagues who conducted the study said in their paper, published in JAMA Network Open, a peer-reviewed journal.

They said that more research was needed to unravel “the underlying causes” of zero-food prevalence, the barriers to optimal adequate child-feeding practices, and the ways socioeconomic factors might influence child-feeding behaviour.

Vandana Prasad, a paediatrician and public health specialist who was not associated with the study, said many infants and toddlers are deprived of complementary feeding because their mothers’ circumstances prevent them from providing the children with feeding care.

“It is not easy to feed children who are six months old — it takes time and energy, and many of the women in households where zero-food children might have been found don’t have the support they require for adequate complementary feeding,” Prasad said.

Mothers in many economically disadvantaged households, whether in rural areas or in urban slums, have to work to earn wages while also managing their household chores, leaving them inadequate time for complementary feeding.

Maternity entitlements and childcare services could help address the issue but many women don’t have access to such services, said Prasad, who’s also a technical adviser to the Public Health Resource Network, a non-government agency that has shown through studies in Odisha how crèches can help reduce under-nutrition levels in children from vulnerable households.

Cultural issues and the lack of information, too, may in some instances affect complementary feeding practices, she said.

Subramanian and his colleagues had last year generated India’s first estimate of the prevalence of zero-food children, based on the 2019-2021 health survey data. Their new study compares prevalence across 92 countries.

The study’s co-authors were Omar Karlsson from Duke University in the US and Rockli Kim, a public health researcher in Korea.