India’s Covid-19 mortality is six to eight times higher than official counts, research released on Wednesday has estimated, reinforcing through a novel methodology earlier suggestions that undercounting had masked the true ferocity of the second wave.

The study has estimated that between 3.2 million people and 3.7 million people had died from Covid by early November 2021, when the Centre’s count based on data from states was around 460,000. The official count has since then increased to over 509,000 deaths.

The estimates by Christophe Guilmoto, a demographer at a French academic institution, are close to the figure of 3.2 million Covid deaths up to July 2021 estimated independently last year by a team led by epidemiologist Prabhat Jha at the University of Toronto, Canada.

Guilmoto used actual Covid deaths in four distinct subpopulations — the population of Kerala, Indian Railways employees, MLAs and MPs, and schoolteachers in Karnataka — to estimate nationwide deaths through a triangulation process.

If the estimates are correct, India would become the country with the highest death toll, well ahead of around 800,000 deaths so far in the US and 600,000 in Brazil. The worldwide death toll would increase from the current 5.8 million.

Health experts not associated with either study said the convergence of estimates from different datasets and analytical methods added credence to concerns about undercounted deaths and challenged assertions by the Union health ministry that such studies were flawed.

“The picture emerging is similar from different sources of data — and it indicates that our mortality figures need to be revised,” said a community medicine specialist at an academic institution, who requested not to be named.

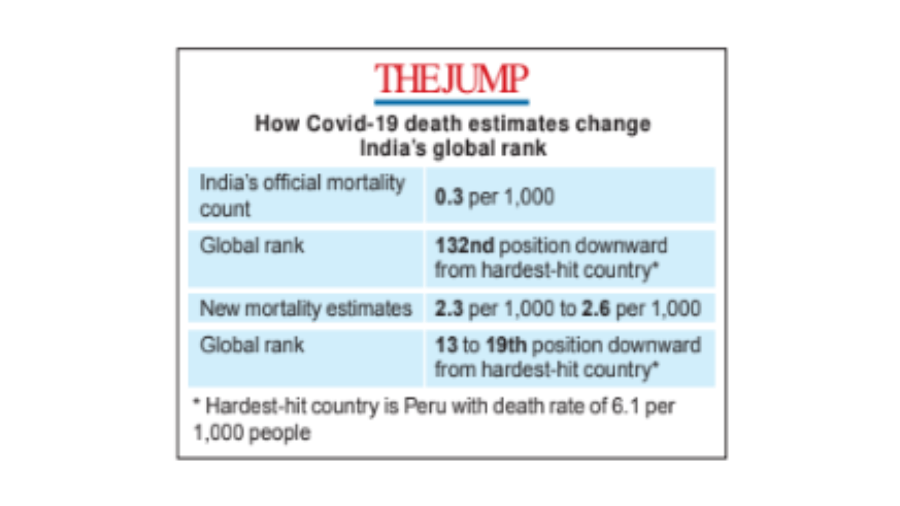

The Narendra Modi government has over the past year often claimed credit for responding quickly and appropriately to the epidemic, citing India’s relatively low Covid population death rate of 0.3 per 1,000 population, half the global average of 0.6.

But the estimated 3.2 million to 3.7 million mortality would increase India’s Covid-19 death rate to 2.3 to 2.6, or about four times the global average of 0.6.

This would place India at rank 13 to 19 downwards from the hardest-hit country — Peru, with a death rate of 6.1 per 1,000 — instead of 132nd rank under official counts.

“The evidence suggesting that the official mortality figures do not capture the reality of what actually happened is growing,” said Guilmoto, a demographer and fellow at the Centre de Sciences Humaines, New Delhi, an institution engaged in social science research.

His peer-reviewed research appeared in the journal PLOS One on Wednesday. The earlier study by Jha and his colleagues that relied on deaths recorded by India’s civil registration system had appeared in the peer-reviewed journal Science last month.

This “pronounced undercount” is probably the joint outcome of under-registration of deaths, the reluctance or inability of families and local authorities to correctly identify Covid-19 as the cause of death, and the faulty attribution of Covid-19 deaths to other causes.

The health ministry has described earlier research reports suggesting that India has undercounted its Covid-19 deaths as flawed, speculative and relying on unproven assumptions. It has said many states have reported “arrear deaths” in a “broadly transparent manner”.

But many health experts have argued that undercounting was obvious last year.

They say the crowds at crematoriums and funeral sites and bodies in rivers during the peak of the second wave during late April and early May 2021 indicated that Covid-19 was killing far more people than India’s body disposal infrastructure could handle.

Experts believe India’s civil registration system is vulnerable to gaps.

“The current civil registration system has little interoperability with health information systems — there is potential for gaps in recording of deaths,” said Oommen John, a physician and research fellow at The George Institute for Global Health, New Delhi, who was not associated with the study.

“A surge in the demand for death registrations only accentuates pre-existing bottlenecks,” he said.

Guilmoto used the 26,628 Covid-19 deaths recorded in Kerala up to October 18, 2021, 43 deaths among India’s 5,837 MLAs and MPs, 1,952 deaths among Indian railway employees, and 268 deaths of schoolteachers in Karnataka to model population mortality for a nationwide estimate.

The methodology is akin to triangulation, a process that uses multiple sources of data to estimate the measure of interest. It used the Kerala mortality data along with intensity of mortality in the other three sub-populations to calculate national-level estimates.

The 43 deaths among MPs and MLAs implies a relatively high death rate of 7.3 per 1,000 in this sub-population, three-fold higher than India’s average of 2.3 per 1,000 under the nationwide estimated 3.2 million deaths.

Guilmoto has reasoned that MPs and MLAs were probably subjected to high levels of exposure to the infection through their interactions with people in their constituencies.

Their activities continued through the pandemic, especially ahead of the Assembly elections in five states between November 2020 and April 2021 and ahead of the panchayat elections in Uttar Pradesh in April 2021, even as India’s second Covid-19 wave rose.

The study observed a death rate of 1.3 per 1,000 among Karnataka schoolteachers and 1.5 per 1,000 among Indian railway employees. Both figures are also higher than the 0.3 per 1,000 figure based on official mortality estimates.

The community medicine specialist who asked not to be named said one way to resolve the uncertainty would be for the Centre to use the nationwide census exercise or household sample surveys to determine how many households had deaths during 2020 and 2021.

“India has roughly 9 million deaths from all causes per year — the census or household surveys would be able to capture excess deaths,” the expert said.